Although it is often written that the King Fuʾād Edition fixed

a somehow unclear text, and established the reading of Ḥafṣ

according to ʿĀsim as predominant, both assertions are rubbish.

How could Islam exist with a chaotic base text? And for about 400 years Ḥafṣ

was by far the most important reading. The three gun-powder empires ‒

Safavid, Timurid/Moghul and Ottoman ‒ had made it their imperial reading,

because it is the easiest for non-Arabs <= the closes to

fuṣḥā.

A second reason could be that Timurids and Ottoman adopted the Kūfī

maḏhab al-Ḥanafiyya.

And like Moroccans follow the Madinese

maḍhab al-Mālikiyya and read according to the Madinese Warš, so most Ḥanifīs read according to Ḥafṣ.

All KFEs have an empty, unpaginated, but counted title page, 826 pages of qurʾanic text

‒ al-fātiḥa being on page 2, an-nās on page 827 ‒ plus 23 pages, 22 being paginated (the last being ت)

In the

KFE II of 1952 the first 845 pages are

roughly identical to KFE I,

the only difference being almost thousand changes in the qurʾānic text and that pages ج and ف are paginated ‒ they used to be counted, but no letter was printed.

No KFE has a prayer

/duʿāʾ.

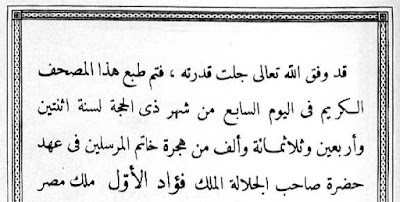

In the last royal edition, KFE II 0, the next page is the impressum of 1924

followed by seven pages

In the large

KFE II a editions (starting in 1953), three pages are gone:

the dedication to King Fuʾād, its empty backside, and the empty page after س

.

The page after س ,the خاتيمة on page ف

is moved to after ض ,something that hurts anyone who understands

abjad.

Before the four pages Table of Suras (without the sura #) an empty page is inserted.

I call "King Fuʾād Edition" all Egyptian Government editions with the last sura on page 827.

Egyptian Government Editions on 522 pages (by the Minstry of Interior) or 525 pages (by the Amīriyya Press) are not KFEs.

Editions by Egyptian commercial publishers (with a title page) are not KFEs.

(Those with the set text of a KFE rearranged with more than 12 line per page (whether original lines or longer one) are definetly not KFEs.)

"Reprints" by publishers in Bairut, Damascus, ʿĀmmān are not KFEs

and can not be trusted: the مصلحة المساحة

is not in

القاهرة

but in Giza.

"Reprints" by foreign countries like China (of KFE I ‒ without the dedication to the King) ‒

and the Kazach (1960)

and Qaṭar (1985) one of KFE II ,

are not KFEs, but sometimes more reliable when it comes to the qur'anic text ‒ just 73:20 is a problem..

Nor is the the Frommann-Holzboog/ITS (Stuttgart 1983) edition a KFE although it has 826 pages of qur'anic text and no title page. Its afterword is set in Stuttgart ‒ the type is not appealing.

The small

kfe II b have nine pages less then the large one of 1952:

the dedication page and its backside, plus the seven pages on changes to the editions before 1952.

There is a

downloadable pdf of the small 1954 print.

There one can see, why the seven pages on the almost thousand changes are missing.

While للطاغين in 78:22 is changed to للطٰغين

, in 38:55 it is changed in the large editions, but not in the small ones.

The change in 7:137 is properly (type set) done

in the large editions (KFE II 0/a),

while it is done by hand in the small editions after 1952 (kfe II b).

By hand are the mīms in the small editions.

on the left the 1924 KFE I, in the middle the large KFE IIa 1952, on the right the small kfe II b after 1952 edition.

While the title box have less information in the 1952 edition, they are the old ones in the small edition.

on top the KFE I, in the middle the Qatari "reprint" of the large 1952 edition, because there is no pdf of either KFE II 0 nor KFE II a online,

below a title box of a small one (kfe II b).

And page 826 of KFE I, KFE II a, and kfe II b (the small plates are not refreshed):

Of the almost thousand changes descriped on the "Seven Pages" only a handful are implemented in the small editions, e.g. the hamza in

qāʾim is not moved down:

The chaos in the Amiriyya editions forces the observer to have a close look at private adaptations.

While the base for Marwān Sawār (Damascus 1983 - 13 lines per page) is a large one with all changes made by aḍ-Ḍabbāʿ (above 13:33 and below)

Ibrāhīm Muʿallim (al-Qāhira Dār Šurūq 1975) sometimes has the old orthography or it is changed by hand,

Sometimes, when done by private hand, it is not worse:

on the left from the large KFE II a, on the right Dar Šurūq:

cf.

in German