My main thesis ‒ on earth there is not THE Standard printed Qurʾān ‒ was already proven by him:

the "official" text of 1342/1924 is not official.

He showed:

the qurʾān was transmitted through the ages both orally and in writing.

the two tansmissions support each other, controll each other.

and: Differences between transmissions are minor.

The sound form (maṣāḥif murattal) and the graphic form of written/printed maṣāḥif differ, but there is only ONE qurʾān.

He wrote this before the age of the internet, of Unicode, before ʿUṭmān Ṭāha, and editions of Qālūn from Damascus, Dubai, Tripoli und Tunis, before one could listen to fourteen riwayāt on CD and TV.

He collected many editions of Ḥafṣ and Warš from Egypt, Iran and Tunisia, and consulted a few manuscripts (in Edinburgh)

At the time, there were no critical editions neither of Zamaḫšarī's Kaššāf nor Sībawaihī's Kitāb. So when a word was given with a different spelling he had to find out, whether it was a typo or a "real" difference.

Neither with typewriters nor on the computer it was easy to write text that had both Latin and Arabic script. Therefore he used a "transliteration" of his own making (not as good as the one deviced by Rüdiger Puin later.

Unfortunately he did not known what a transliteration is, confused it with transcription.

transliteration renders the letters of the original unambiguously/objectivly, best one-to-one and onto

hence it is reversable (without deep knowledge of the languages)does not need to be speakable. transcription renders the sounds of the original in the second language; should be pronouncable after a short instruction: is not reversable without knowing the languages well, which is not the case for Brockett's "transliteration". I can't read it, I have to rely on chapter and verse. The tilde sometimes stands for "not in the rasm" sometimes for "extra-long". Some of his terms are just stupid.

At least he defines them before using them.

"graphic" signifies "written in the rasm,"

"vocal" for "not in the rasm" ‒

"The term 'vocal form', with respect to the Qur'ān, is used throughout to signify the letter skeleton fully fleshed out with diacritical marks, vowels, and so on."

is nonsense:

1. his "vocal" is not the sceleton fully fleshed out" but; "only the flesh (= diacritics) without the sceleton" 2. in the Qurʾān there are non consonats, but just letters 3. the letter sceleton is not mute (avocal) and dots, strokes and signs are not all and only about sound, both are written AND spoken, are both graphic and phonetic. What he wants to say is: some signs are there from the beginnings , others were added later: diacritical dots (although some dots were there in the earliest mss.), vowel signs (harakat), tašdīd, hamza sign, waṣla sign, signs for , signs for Imala, Išmām, assimilation, non-pronounciation (either always or when no pause is made) of written letters, consonats having no voyel (unmoved as they say in Arabic), Nachdruck, Abschwä&chung, Überdehnung.

Es gibt also auch Zeichen, die geschrieben wurden, aber nicht gesprochen; außerdem Aussprachephänomene, die nur in guten Ausgaben geschrieben werden (wie Nasalierung, Assimilation, Deutlichkeit, Nachdruck) <beim Letztgenannten ist zu unterscheiden: Buchstaben, die immer nachdrücklich sind, welche, die in der Umgebung nachdrücklich sind und solchen, die ausnahmsweise nachdrücklich sind ‒ nur das Dritte muss notiert werden>

3.) Obwohl er "definiert": The term 'graphic form' refers to the bare consonantal skeleton, meint er auch dies nicht; er meint rasm+diakrit.Punkte ‒ und "vocal" für den Rest.

Da seine Arbeit immer noch das Beste ist, was auf Englisch dazu vorliegt und ich sie auch ausschlachten will, erst die Kritik ‒ das haben wir dann hinter uns. Die eklatanten Fehler liegen daran, dass es eine Doktorarbeit ist, keine Publikation. Der Autor war jung und unerfahren und er durfte sie niemandem zur Korrektur, Ausbessern, Ausdiskutieren vorlegen. Es sollte ja keine fertige Arbeit sein, sondern nur ein Nachweis dafür, dass er wissenschaftlich arbeiten könnte, und das zeigte er nicht nur bei der Manuskriptdatierung anhand der Wasserzeichen und den kritischen Fußnoten zur verwendeten Literatur, sondern auch mit dem Aufstellen und Belegen von Thesen.

Kurios ist, dass er den 1924er Druck für die Wiedergabe einer Handschrift hielt.

dass er den 1982er qatarischen Reprint für den Reprint dieses Druckes hielt,

obwohl es sich um einen Reprint des (an über 900 Stellen abweichenden) 1952er Druckes handelt,

dass er ein Kolophon zitiert, in dem Ḥasan Riḍā als Schreiber genannt wird, er aber "Āyat Barkenār" für den ‒ ihm unbekannten ‒ Kalligraphen hält.

Dass er glaubt, dass man 1978 aus Pakistan Druckplatten nach Johannesburg transportierte, um einen Tāj-Ausgabe nachzudrucken, zeigt, dass er von Drucktechnik null Ahnung hatte, weshalb ich die vielen Anmerkungen zu diesem Aspekt völlig ignoriere (wenn ich die von ihm konsultierten Ausgaben zur Hand hätte oder von ihm erfahren könnte, worauf er seine Bemerkungen stüzt, wäre es anders.)

Zum Glück habe ich fast alle von ihm erwähnte Ausgaben ‒ sei es gebunden, sei es als pdf. Für die Ausgaben aus Delhi, Bombay und Calcutta habe ich immerhin äquivalente. Ich kann deshalb die meisten seiner Angaben nachvollziehen. Und für Anderes habe ich zusätzliche Belege.

Nirgends komme ich zu anderen Schlussfolgerungen.

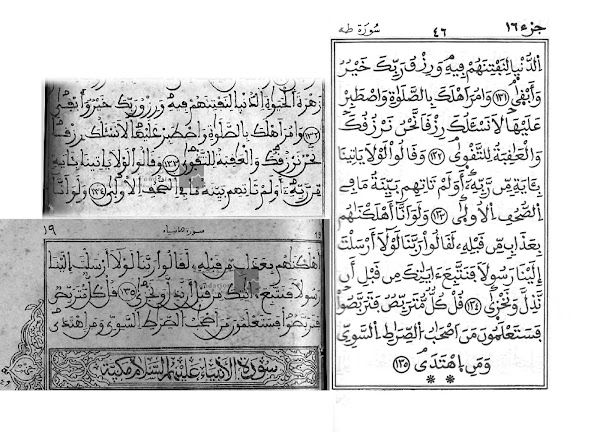

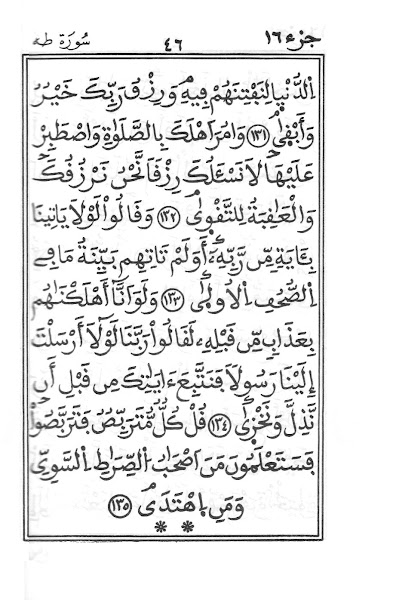

Ging es bisher hauptsächlich um Ḥafṣ-Ausgaben, wollen wir jetzt noch einen Blick auf andere Lesarten werfen, dabei geht es vor allem um Äußerlichkeiten. Beginnen wir mit den „unerheblichen Buchstaben“ (al-ḥurūf al-yasīra): den ganz wenigen Unterschieden, die nicht durch šadda, fatḥa, kasra, ḍamma, hamza, madda oder diakritische Punkte ausgedrückt werden, sondern im rasm.

Ibrāhīm hat bei Ḥafṣ weder alif noch yāʾ, bei Nāfīʿ jedoch yāʾ – ich sage nicht Warš, weil es in den drei Zeilen nicht den geringsten Unterschied zwischen beiden riwāyāt gibt – für dies hier ein Beispiel: Während Qālūn mit hamza zu sprechen ist, ist es bei Warš geschwächt. (Schreibungen von Uṭmān Ṭaha für den KFK.)Während der Vers bei Ḥafṣ mit wa- beginnt, fehlt dies bei Qālūn.

Beide Male hat Ḥafṣ ein alif mehr: erst in der Mitte der Zeile, auf der nächsten Seite in Zeile Zwo (ʾauʾan vs. waʾan). Man beachte das winklige ḍamma, in Unicode ein anderes Zeichen.

Im Netz findet man Viel zu Unterschieden zwischen Ḥafṣ und Warš. Viele wollen damit beweisen, dass die muslimische Überlieferung unzuverlässig ist. Oder sie wollen herausbekommen, welches der richtige qurʾān ist. Oder sie behaupten, die Unterschiede seien nur phonetisch. Wirklich gut bei der Darstellung der Unterschiede und bei deren Bewertung ist Adrian A. Brockett. Hier einige seiner Unterschiede.

Ḥafṣ Warš Stelle

-kum, -hum, -him, -kumu, -humu, -himu,

-tum, -tumu bzw. -kumū xxx …

Ḥafṣ Warš Stelle

yaḥsabuhumu yaḥsibuhuma 2:273

taḥsabanna taḥsibanna 3:169

أَتُحَـٰٓجُّوٓنِّي أَتُحَـٰٓجُّونِي 6:80

سَوَآءٌ عَلَيۡهِمۡ ءَأَنذَرۡتَهُمۡ سَوَآءٌ عَلَيۡهِمُۥ ءَآنذَرۡتَهُم 2:6

أَتُمِدُّونَنِ أَتُمِدُّونَنِۦ 27:36

قُلۡ ءَأَنتُمۡ أَعۡلَمُ ڧُل̱ۡ آنتُمۡۥۤ أَعۡلَمُ 2:140

وَإِنِّيٓ أُعِيذُهَا وَإِنِّيَ أُعِيذُهَا 3:36

هَـٰٓأَنتُمۡ هَآنتُمُۥۤ 3:119

إِنِّيٓ أَعۡلَمُ إِنِّيَ أَعۡلَمُ 2:30

هَـٰٓؤُلَآءِ إِن هَـٰٓؤُلَآءِ ؈ں 2:31

5:3 faman iḍṭurra faman uḍṭurra

أَوۡ إِثۡمًۭا أَواِثۡمًۭا 2:182

أَوِ ٱخۡرُجُواْ أَوِ ﰩخۡرُجُواْ 4:66

قَرِيبٌ أُجِيبُ ڧَرِيبٌ اجِيبُ 2:186

6:10 ..qad istuhziʾa ..qad ustuhziʾa

بِئۡسَمَا يَأۡمُرُكُم بِيسَمَا يَامُرُكُم 2:93

نَبِيًّۭا نَبِيـًۭٔا 3:39

وَٱلصَّـٰبِـِٔينَ وَالصَّـٰبِـيںَ 2:62

ٱلنَّبِيَّ ؇لنَّبِيٓءَ 7:157

تُسۡـَٔلُ تَسۡـَٔلۡ 2:119

أَؤُنَبِّئُكُم اَو۟ ۬ نَبِّئُكُم 3:15

تُسَوَّىٰ تَسَّوّٜىٰ 4:42

Warš-Drucke erscheinen 1879 und 1891 als großformatige, dreifarbige Steindrucke in Fez; in den 1890ger gibt es jährlich kleinere Drucke in schwarz-weiß. Um 1900 erscheint der erste in Algerien.

The first muṣḥaf printed in Morocco was printed in 1296/1879 in Faz. It has 19 lines on a page, and uses black, red and blue keine Änderungen The next one has 25 lines per page: one from 1313/1895/6 1331/1911/2 ar-Rūdūsī bn Murād at-Turkī from the island of Rhodes living in Algiers prints a muṣḥaf with 14 lines in his maṭbCat aṯ-ṯaCAlibiyya The edition of 1350/1931 can be downloaded in the net at several sides. Instead of the counting "Madina 2" "Kufa" is used ((these days, other publisher both in Damascus and in Algiers use the Kufī numbering -- on the right the Tijani print: Qurʾān Ma¬ǧīd, Alger: Ma¬ṭbaʿa aṯ-Ṯaʿālibīya 1356/1937 mit farbigem ʿanwān another one from the web site of the Foundation du Roi Abelaziz in Casablanca: first pages and last of a muṣḥaf in two volumes, 19 lines per page In der Zeit zwischen den Weltkriegen stiegen ägyptische Verlage in das Geschäft ein, hier Beispiele aus einer Werbebroschüre von Muṣṭafā al-Bābī al-Ḥalabī. 1929 in Egypt, where it was printed ‒ dedicated to Sulṭan Muḥmmad [V.] bn Yūsuf This Cairo Warš Edition, Cairo 1929 Edition, al-Ḥabbābī edition, Zwīten edition is the first Moroccan edition with numbers after each verse, and ‒ a revolution of sorts ‒ Kufī numbers; so ʿAlī Muḥammad aḍ-Ḍabbāʿ (1304/1886-1380/1960) writes four pages on the differences between (second) Madani and Kufi mumbering (pages 8-11): the cover of the first edition the first three pages: instead of a title page: (this is from the copy of the Academy of Sciences in Lissabon that is not paginated in quarters, but in halves; its index and the duʿāʾ are set in normal Arabic letters, while handwritten in the original.) the ʿanwān of the first edition So are no pagination. As often, THE Zwīten does not exist, the original one is divided into four parts, and has before the quranic text faḍl al-qurʾān and ādāb at-tilāwa; all is handwritten, the last four pages in eastern nasḫ pointed like in the east (no dots on final nūn, fā' and qāf, fā'-dot below, single qāf-dot above), all other parts in maġribi masbūṭ, while the Lissabon copy (in halves) lacks most additions. Maybe these two strange pages are due to merging quarters into halves (??) Or to have the ḥizb start on a new page? Normal pages have 15 lines last page of first half With a book seller I found a last quarter printed in 1990. In Algeria Sufi fraternities had editions of their own: Šaḏilī Tijani printed on salmon paper, printed at the expense of Tijani al-Muhammadi, owner of the al-Manar Press and Library, who was also responsible for calligraphy and decoration Tunisia 1365/1945/6 ‒