In recent times the government had to destroy many imported copies because of mistakes, notably 25 years ago sinking a whole load in the Nile.As no year is given, no information of the kind of mistakes, no information on the printer ("Ausland") nor the importer, nothing on whom paid an compensation for the capital destroyed to whom (how much?), I do not believe it. The are serveral kind of mistakes possible: ‒ those that are not mistakes at all, just different convention (like whether a leading unpronounced alif carries a head of ṣād as waṣl-sign or not, or some otiose letters ‒ see earlier posts) ‒ type errors, that can be remedied by including a "list of errors" or by correcting them by hand ‒ binding error: several copies lack a quire having another one twice, or quires in the wrong order. Copies with binding error can not be sold. That you have to destroy hundreds of copies, there must be so many mistakes that it is virtually impossible to correct them by hand. So far Bergstäßer just reports what was written in the brochure. Now he tells us what the šaiḫ al-maqāriʾ Muḥammad ʿAlī Ḫalaf al-Ḥusainī al-Ḥaddād told him, but here he does not use the subjunctive of indirect speech, he gives obvious ("natürlich") facts.

Quelle für den Konsonatentext sind natürlich nicht Koranhandschriften, sondern die Literatur über ihn; er ist also eine Rekonstruktion, das Ergebnis einer Umschreibung des üblichen Konsonantentextes Of course, the source for the consonant text are not manuscripts, but the literature about it; it is therefore a reconstruction, the result of a rewriting of the usual consonant textThe source given for the rasm is a didactic poem Maurid aẓ-ẓamʾān by al-Ḫarrāz based on Abū Dāʾūd Sulaimān ibn Naǧāḥ's ʿAqīla but the Indonesian Abdul Hakim ("Comparison of Rasm in Indonesian Standard Mushaf, Pakistan Mushaf and Medinan Mushaf: Analysis of word with the formulation of ḥażf al-ḥuruf" in Suhuf X,2 12.2017), the Iranian Center for Printing and Spreading the Quran and the scholars advising the Tunisian publisher Hanbal/Nous-Mêmes have checked the text (either all of it or "just" a tenth ‒ from different parts) and found out, that the text of the King Fuʾād Edition and the King Fahd Edition do not tally with the ʿAqīla. While the Muṣḥaf al-Jamāhīriyya follows ad-Dānī's Muqniʿ all the time and the Iranian Center and the Indonesian Committee publish lists with words where they follow which authority (or in the case of the Iranian center even apply a different logic) al-Ḥusainī al-Ḥaddād and the Medinese King Fahd Complex claimed (!) to follow Abū Dāʿūd. As this is clearly not the case "Medina" and "Tunis" inserted a word in the explanations: ġāliban or fil-ġālib (mostly) and a caveat "or other experts." So: the KFC admitts that they do NOT follow Abū Dāʾūd all the time. Al-Ḥusainī al-Ḥaddād had told Bergsträßer what the orientalist wanted to hear. All professional recitors in Egypt know the differences between Ḥafs, Warš and Qālūn by heart. Being the chief recitor and a Malikite, he knew Warš even better than most. So what he really did, he copied an Warš copy into a Ḥafs script ‒ largely Abu Dāʾūd, but not 100 %. So the KFE was not a revolution, just a switch from Asia to Africa: a "no" to the Ottomans, a "yes" to the Maġrib. As I have already said, I recomment an old text. Gabriel Said Reynolds writes rubbish:

The common belief that the Qur’an has a single, unambiguous reading ... is above all due to the terrific success of the standard Egyptian edition of the Qur’an, first published on July 10, 1924 (Dhu l-Hijja 7, 1342) in Cairo, an edition now widely seen as the official text of the Qur’an. ... Minor adjustments were subsequently made to this text in following editions, one published later in 1924 and another in 1936. The text released in 1936 became known as the Faruq edition in honor of the Egyptian king, Faruq (The Qur’an in Its Historical Context, London New York 2008. p. 2)All wrong. The King Fuʾād Edition was not published on July 10, 1924, but the printing of its qurʾānic text was finished on that day. It was really only published after the book was bound in the next year according to the embossed stamp on its first page ‒ or just the second run of the first edition was stamp like this (?).

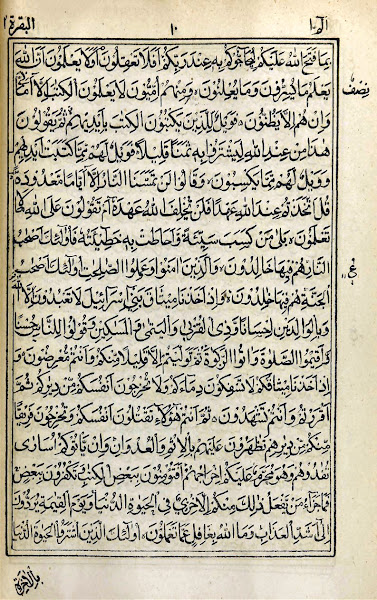

طبعة الحكومية المصرّية

-- . --

١٣٤٣ هجرّية

سـنة

There were minor changes between 1343/1925 and 1347/1929 either in the quranic text or in the information that follows it, but there were no changes in 1936; there never was an Faruq (or Farūq) edition; until the revolution of 1952 all full editions of the qurʾān by the Government Press were dedicated to King Fuʾād. How comes that some youngster call the "King Fuʾād Edition" "The Cairo Edition" or "the Azhar Edition"? My guess: because they are so young, too young to have spent days in the book shops and publishers around the Azhar. From 1976 to 1985 the most common edition was the "muṣḥaf al-Azhar aš-šarīf" printed by the Amiriyya in many different format, big and small, cheap and expenisve ‒ all with the qurʾānic text on 525 pages with 15 lines and only three pause signs (not to be confused with the "muṣḥaf al-Azhar aš-šarīf" by the Azhar, which is a reprint of the 522 page muṣḥaf written by Muṣṭafa Naẓīf.) But these youngster do not know that there is an "Azhar edition" that came 50 years after the KFE saw the light of day. And "muṣḥaf al-Qāhira" was the huge manuscript attributed to ʿUṯmān kept at al-Ḥusainī Mosque north of al-Azhar. From 1880 to today there were more than a hundred editions produced in al-Qāhira, in an industial area nearby, around the main railway station and in Bulāq, no person aware of this could imagine "The Cairo edition", ‒