this is a Google translation of one of my German posts

this is a Google translation of one of my German posts

Showing posts with label Giza24. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Giza24. Show all posts

Thursday, 6 June 2024

Giza1924, KFE I

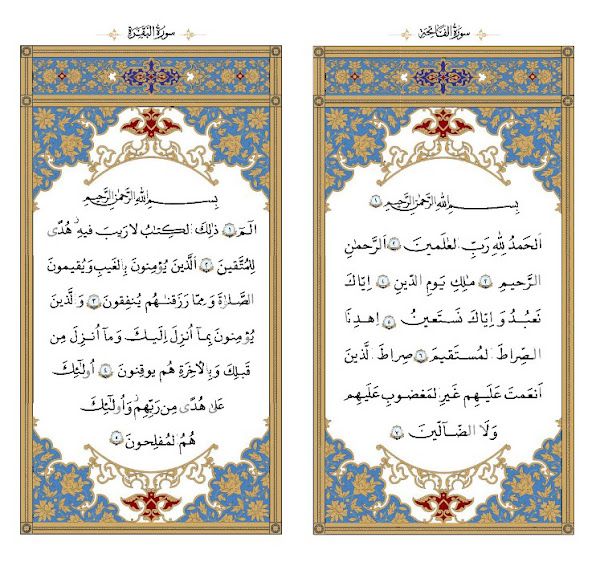

The Giza Qurʾān

‒ is not an Azhar Qurʾān

‒ did not trigger a wave of printings of Qurʾāns,

because there was finally a fixed, authorized text

‒ the King Fuʾād Edition was not immediately accepted by Sunnis and Shiites

‒ did not contribute significantly to the spread of the reading of Ḥafṣ,

it was neither published in 1923 nor on 10 July 1924.

But it drove the abysmally bad Gustav Flügel edition out of German study rooms,

‒ had an afterword by named editors,

‒ gave its sources,

‒ took over ‒ apart from the Kufic counting,

and the pause signs, which were based on Eastern sources

‒ the Maghrebi rasm (mostly/ġāliban) according to Abū Dāʾūd Ibn Naǧāḥ)

‒ the Maghrebi small fall back vowels for lengthening

‒ the Maghrebi subdivision of the thirtieths (but without eighth-ḥizb)

‒ the Maghrebi baseline hamzae before leading Alif (ءادم instead of اٰدم).

‒ the Maghrebi missspelling of /allāh/ as /allah/

‒ the Maghrebi spelling at the end of the sura, which assumes that the next sura is recited immediately afterwards (without Basmala): tanwin is modified accordingly.

‒ the Maghrebi distinction between three types of tanwin (one above the other, one after the other, with mīm)

‒ the Maghrebi absence of nūn quṭni.

‒ the Maghreb non-writing of vowel shortening

‒ the Maghrebī (and Indian) notation of assimilation

‒ the Maghrebī (and Indian) attraction of the hamza sign by kasra

in G24 the hamza is below the baseline ‒ in the Ottoman Empire (include Egypt) and Iran the hamza stays above the line

New was the differentiation of the Maghreb Sukūn into three characters:

‒ the ǧazm in the form of a ǧīm without a tail and without a dot for no vowels,

‒ the circle as sign: should always be ignored,

‒ the (ovale) zero for sign: should be ignored unless one pauses thereafter.

‒ plus the absence of any mute (unpronounced) character.

‒ word spacing,

‒ Baseline orientation and

‒ exact placement of diacritical dots and ḥarakāt.

It was also not the first "inner-Muslim Qurʾān print" (A.Neuwirth).

Neuwirth may know a lot about the Qurʾān, but she has no idea about Qurʾān prints,

since there have been many prints by Muslims since 1830, and very, very many since 1875

and Muslims were already heavily involved in the six St. Petersburg prints from 1787-98.

It was not a type print either, but - like all except Venice, Hamburg, Padua, Leipzig,

St. Petersburg, Kazan, one in Tehrān, two in Hooghli, two in Calcutta and one in Kanpur

- planographic printing, although no longer with a stone plate, but with a metal plate.

It was also not the first to declare to adhere to "the rasm al-ʿUṯmānī“.

Two title pages from Lucknow prints of 1870 and 1877.

In 1895 appeared in Būlāq a muṣḥaf in the ʿUthmani rasm, which perhaps meant "unvocalized."

Kitāb Tāj at-tafāsīr li-kalām al-malik al-kabīr taʼlīf Muḥammad ʿUthman ibn as-Saiyid

Muḥammad Abī Bakr ibn as-Saiyid ʻAbdAllāh al-Mīrġanī al-Maḥǧūb al-Makkī.

a-bi-hāmišihi al-Qurʼān al-Maǧīd marsūman bi’r-rasm al-ʿUṯmānī. Except for the sequence IsoHamza+Alif, which was adopted from the Maghreb in 1890 and 1924 (alif+madda didn't work because madda had already been taken for lengthening), everything here is as it was in 1924.

The text of the KFA is not a reconstruction, as al-Ḥusainī al-Ḥaddād al-Mālikī

had told G.Bergsträßer: It does not exactly follow

Abū Dāʾūd Sulaiman Ibn Naǧāḥ al-Andalusī (d. 496/1103)

nor Abu ʿAbdallah Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad al-Ḫarrāz (d. 718/1318),

but (except in about 100 places) the common Warš editions.

The adoption of many Moroccan peculiarities (see above),

some of which were revised in 1952, plus the dropping of Asian characters ‒ plus the fact that the afterword is silent on both ‒ is a clear sign

that al-Ḥusainī al-Ḥaddād al-Mālikī adapted a Warš edition.

All Egyptian readers knew the readings Warš and Qālun.

As a Malikī, al-Ḥusainī al-Ḥaddād probably knew Warš editions

even better than most.

The text, supposedly established in 1924, was not only available in the Maghreb and

in Cairo Warš prints, but also in Būlāq in the century before.

Now to the publication date.

You can find 1919, 1923, 1924 and 1926 in libraries and among scholars.

According to today's library rules, 1924 applies because that is what it says in the first print

But it is not true. It says in the work itself that its printing was on 10.7.1924. But that can only mean that the printing of the Qurʾānic text was completed on that day. The dedication to the king, the message about the completion of printing, could only have been set afterwards; it and the entire epilogue were only printed afterwards, and the work - without a title page, without a prayer at the end - was only bound afterwards - probably again in Būlāq, where it had already been set and assembled - and that was not until 1925, unless ten copies were bound first and then "published", which is not likely.

Because Wikipedia lists Fuʾād's royal monogram as that of his son, here is his (although completely irrelevant): this is a Google translation of one of my German posts

this is a Google translation of one of my German posts

this is a Google translation of one of my German posts

this is a Google translation of one of my German posts

Sunday, 14 April 2024

a book by Saima Yacoob, Charlotte, North Carolina

At the start of this year's Ramaḍān Saima Yacoob, Charlotte, North Carolina published a book on differences between printed maṣāḥif. Although her starting point and her conclusions are worthy, the book is full of mistakes.

Let's start with the positive:

• I believe that it would be a great loss to our ummah if we were to insist on abandoning [the existing] diversity [in] apply[ing] the rules of ḍabṭ ... • The framework of the science of ḍabṭ is that diacritics be used to ensure that the Qurʾān can be recited correctly by the average Muslim, and that there is enough regional standardization ... that the people of an area may read the Qurʾān correctly through the maṣāḥif published ... in that area. • Because of the flexibility [in] the science of ḍabṭ, new conventions of ḍabṭ may be added even today to meet the changing needs of Muslims in a particular region. A modern example of this is the tajwīd color coded maṣāḥif.This is an important point: maṣāḥif do not have to be identical to be valid. Only the last remark is wrong: color coded maṣāḥif are not "particular [to a] region". I will give an example that springs from a particular region: The Irani Muṣḥaf with simple vowel signs: While we used to have two basic ways of writing vowels (the Western/"African" with three vowel signs, sukūn, and three small lengthening letters, the Eastern/"Asian" with three short vowel signs, three long vowel signs, and sukūn/ǧasm)); now there is a third (the new "Iranian" with six vowel signs in which the sign for /ū/ is not a turned ḍamma as in Indo-Pak and Indonesia, but looks like the Maġribian/Afro-Arab small waw, without sukūn, but with a second color for "silent, unpronounced"): Only the vowel signs count, vowel letters are ignored when the consonant before has a vowel sign and they have none; when a consonant has no vowel sign it is read without vowel (sukūn is not needed). When a "vowel letter" has a vowel sign, it is a consonant. There is no head of ʿain on/below alif (when there is a vowel sign, hamza is spoken). There are no small vowel lettes ‒ instead of "turned ḍamma/ulta peš" a small waw is used: it look like the small letter used in the West/Maghrib/Arab Countries, but is a vowel sign. The main point of Differing Diacritics is: there are different ways to mark the fine points, and that's okay. The maṣāḥif have the same text, but the notation is not exactely the same. On page 2 of the book the diactrics are defined. Šaiḫa Saima Yacoob states that there are three kinds: 1.) "letters that are additional or omitted in the rasm" 2.) "fatḥah, kasrah, ḍammah, shaddah, etc." "Thirdly, those markings that aid the reader to apply the general rules of tajwīd correctly, such as the sign for madd, or a shaddah that indicates idghām, etc." ALL wrong. First come the dots that distinguish letter with the same shape: د <‒>ذ ص <‒> ض ب <‒> ن ي ط <‒> ظ Second: fatḥa, kasra, ḍamma, šaddah, sukūn, plus in "Asia" turned fatḥa, turned kasra, turned ḍamma Third: tanwīn signs and signs for madd ‒ in Asia there are three kinds of madd signs, in "Africa" three kinds of tanwīn signs for each of the short vowels ‒ small vowel "letters that are additional or omitted in the rasm" exist only in the African/Andalusian/Arab system the tiny groups of small consonant letters (sīn, mīm, nūn) that modify pronounciation, and the signs for išmām and imāla come fourth and fifth. (In Turkey "qaṣr" and "madd" are a sixth group.) On page 4 the šaiḫa writes: "the reader could easily get confused by the two sets of dots, those for vowels, and those that distinguished similarly shaped letters from each other" I disagree: the dots for vowels are in gold/yellow, green, red or blue (and usually big), those distinguishing letters with the same base form are in black (like the letters, because they are part of the letters). How can one confuse (big) coloured and (smaller) black dots? BTW, "distinguished similarly shaped letters from each other" ‒ what I called the first function of diacritics ‒ is missing from her definition of ḍabṭ on page 2. Yacoob sometimes repeats what is written in well known books, but makes no sense: "symbols [for vowels] were taken from shortened versions of their original form, such as ... a portion of yāʾ for kasrah" (p.4). While fatḥa and ḍamma look like small alif resp. waw, kasra is neither a shortened yāʾ nor a part of yāʾ ‒ to me it looks like a transposed fatḥa.

Unfortunately, I found very little information about the ḍabṭ of the South Asian muṣḥaf in Arabic. (p. 7)okay, she did not find anything, but it is available and it is all in Arabic (although written by a Muslim from Tamil Nadu).

the Chinese muṣḥaf. (p. 7)As far as I know, there is no printed Chinese muṣḥaf, definetly not "the Chinese muṣḥaf". I have two maṣāḥif from China: a Bejing reprint of the King Fuad Edition of 1924/5 and a Kashgar reprint of the Taj edition with the text on 611 pages like the South Asian one printed by the King Fahd Complex. That a reprint of a Taj edition follows the IndoPak rules goes without saying, but that is not "the Ch. m."! Enough, it goes on like this: mistake after mistake. I don't understand how a careful person can write a book like this ‒ and not revise it in due course.

Wednesday, 26 May 2021

Giza 1924 ‒ better ‒ worse

The Egyptian Goverment Edition printed in Gizeh in 1924

was the first offset printed mushaf,

It was type set (not type printed).

It used smaller subset of the Amiriyya font not because the Amiriyya laked the technical possibility for more elaborate ligatures,

((in 1881 when they printed a muṣḥaf for the first time,

they used 900 different sorts, in 1906 they reduced it to about 400,

which they used in the backmatter of the 1924 muṣḥaf, in the qurʾānic text even less))

but to make the qurʾānic text easier to read for state school educated (wo-)men.

They did not want that the words "climb" at the end of the line for lack of space,

nor that some letter are above following letters.

It is elegant how the word continues above to the right of the baseline waw, but it is against the rational mind of the 20th century: everything must be right to left!

The kind of elegance you have with "bi-ḥamdi rabbika" is not valued by modern intelectuals. Here you see on the right /fī/, on the left /fĭ/, a distinction gone in 1924: And here you see, with which vowel the alif-waṣl has to be read ‒

something not shown in the KFE.

In Morocco they always show with which vowel one has to start (here twice fatḥa), IF one starts although the first letter is alif-waṣl, the linking alif, with is normaly silent.

In Persia and in Turkey one shows the vowel only after a pause, like here:

Both in the second and third line an alif waṣl comes after "laziM", a necessary pause, so there is a vowel sign between the usual waṣl and the alif ‒ a reading help missing in Gizeh 1924.

It was type set (not type printed).

It used smaller subset of the Amiriyya font not because the Amiriyya laked the technical possibility for more elaborate ligatures,

((in 1881 when they printed a muṣḥaf for the first time,

they used 900 different sorts, in 1906 they reduced it to about 400,

which they used in the backmatter of the 1924 muṣḥaf, in the qurʾānic text even less))

but to make the qurʾānic text easier to read for state school educated (wo-)men.

They did not want that the words "climb" at the end of the line for lack of space,

nor that some letter are above following letters.

It is elegant how the word continues above to the right of the baseline waw, but it is against the rational mind of the 20th century: everything must be right to left!

The kind of elegance you have with "bi-ḥamdi rabbika" is not valued by modern intelectuals. Here you see on the right /fī/, on the left /fĭ/, a distinction gone in 1924: And here you see, with which vowel the alif-waṣl has to be read ‒

something not shown in the KFE.

In Morocco they always show with which vowel one has to start (here twice fatḥa), IF one starts although the first letter is alif-waṣl, the linking alif, with is normaly silent.

In Persia and in Turkey one shows the vowel only after a pause, like here:

Both in the second and third line an alif waṣl comes after "laziM", a necessary pause, so there is a vowel sign between the usual waṣl and the alif ‒ a reading help missing in Gizeh 1924.

Monday, 27 July 2020

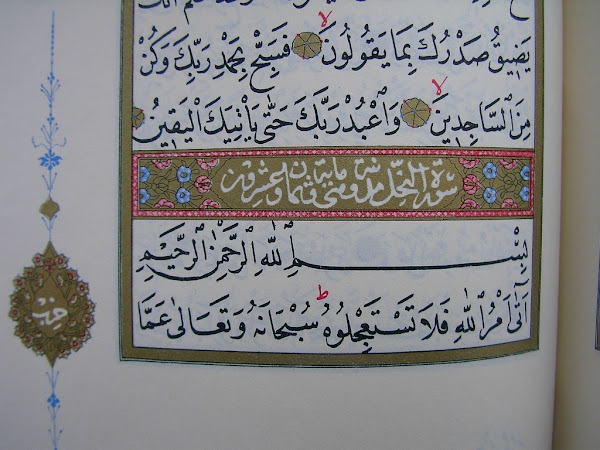

Gizeh 1924 <> Cairo 1928 and after

See the end of Sura 73 in the Gizeh 1924 print (on the left)

and Cairo 1928 (on the right, slightly enlarged -- the Cairo print is a bit smaller and has much less margin).

First line الن and ان لن

In 1952 it's back to الن

The Bairut (Paris, Amman) reprints oscillate between the two.

The original Damascus ʿUṯmān Ṭaha has one word:

So has the first Saudi reprint: But the next, the first done in the new printing complex, has two:

and Cairo 1928 (on the right, slightly enlarged -- the Cairo print is a bit smaller and has much less margin).

First line الن and ان لن

In 1952 it's back to الن

The Bairut (Paris, Amman) reprints oscillate between the two.

The original Damascus ʿUṯmān Ṭaha has one word:

So has the first Saudi reprint: But the next, the first done in the new printing complex, has two:

Sunday, 10 March 2019

The Ḥafṣ ʿan ʿĀṣim King Fuʾād 1924/5 edition

I have just published an essay on Qurʾān prints on Amazon:

I want to blog about that and from it here.

(this is my German post translated by deepl)

In the course of time I will probably bring everything from the book - but slowly...

Since 1972, when thousands of very old Qurʾān fragments were discovered in a walled-up attic of the Great Mosque of Ṣanʿāʾ, more precisely since 2004, when Sergio Noga Noseda was allowed to produce high-resolution colour photographs, since scholars have recognised that leaves kept in up to seven different collections formed one codex and that they can be studied thanks to online and printed publications.

Since thousands of short texts carved in stone from Syria, Jordan and Sa'udi Arabia can be read (ever better), research into the Arabic language and script of the centuries immediately before and after Muḥammad has been the most exciting part of Islamic studies.

Since the destruction of the Twin Towers in Manhattan, reflections on Islam as a late ancient civilisation and/or religion related to Judaism and Christianity have been particularly popular.

Unfortunately, experts in these interesting fields also comment on a subject they have not studied ‒ because it is not interesting enough - and write almost nothing but nonsense about it.

The field of printed editions of the Qur'an needs to be cleaned up. And that is what I want to do here. Many German Orientalists refer to the official Egyptian edition of 1924/5 as "the standard Qur'an", others call it "Azhar Qur'an". Some call it "THE Cairo Edition/CE" ‒ utter nonsense. Many false ideas circulate about the King Fuʾād edition, the Giza Qur'an, the Egyptian Survey Authority print (المصحف الشريف لطبعة مصلحة المساحة المصرية), the 12-liner (مصحف 12 سطر). Some believe they are looking at a manuscript, Andreas Ismail Mohr and Prof. Dr. Murks call it "type printing". Yet the epilogue ‒ from 1926 even more clearly than the first one (1924/5) ‒ makes everything clear: The book written by Egypt's šaiḫ al-maqāriʾ Muḥammad ibn ʿAlī ibn Ḫalaf al-Ḥusainī al-Mālikī aṣ-Ṣaʿīdī al-Ḥaddād (1282/1865-1357/ 22.1. 1939) ‒ not to be confused with the calligrapher Muḥammad ibn Saʿd ibn Ibrāhīm al-Ḥaddād (1919-2011) ‒ was set in Būlāq with five tiers per line (pause signs; fatḥa, damma, sukūn; letters [for baseline hamza including the vowel sign]; kasra; spacing).

Type printing is a letterpress process. The types/sorts leave small indentations on the paper: the types/sorts press the printing ink into the paper. Offset is planographic: the paper absorbs the ink; you can't find indentations. With his eyes, Mohr saw that it was not handwritten. But he does not know that type print can only be recognised with the sense of touch (not by vision). And neither did Prof. Dr. Murks.

"That's nonsense, instead of elaborately typesetting and printing that ONCE, why not have a calligrapher write it?" This fails to appreciate the technoid sense of accuracy of the editors of 1924. To this day, there is no one except ʿUṯmān Ṭaha (UT) who is as accurate as the typesetting or the computer.

Two examples to illustrate.

While UT clearly reads yanhā, the beautiful Ottoman handwriting reads naihā; while the three vowel signs (fatḥa, sukūn, Lang-ā) are clearly in the right order (there is no other way, they are all on top), nūn (perhaps) comes before yāʾ (does the nūn dot come before the yāʾ dots). Incidentally, the two "tooth" letters have a tooth or spine in UT, but none in court Ottoman! While there is clearly nothing between heh (I use the Unicode name to clearly distinguish it from ḥāʾ) and alif maqṣūra in UT, there could well be a tooth in Ottoman: You only needed to put two dots over it and it would be hetā or something like that.

Second example: wa-malāʾikatihī Whereas in the 1924/5 Qur'an (below) and UT (in the middle) there is a substitute alif-with-madda hovering BEFORE the tooth above the baseline, in Muṣḥaf Qaṭar (above) there is a hamza-kasra hovering AFTER the change alif-with-madda below the baseline, which changes the yāʾ-tooth into a (lengthening) alif. There is nothing wrong with this (sound and rasm are the same, after all), but it is a different orthography and should not be, according to the conception of people who do not tolerate any approximation in the Qur'an.

Now the whole of page 3 in comparison. Giza print and UT: the Amiriyya is more calligraphic than UT, which can be seen in the examples in the right margin.

All in all, UT follows the default. Baseline and clear from right to left. Only in the spacing between words is it less modern than the Amiriyya (which is why Dar al-Maʿrifa increased the spacing).

I want to blog about that and from it here.

(this is my German post translated by deepl)

In the course of time I will probably bring everything from the book - but slowly...

Since 1972, when thousands of very old Qurʾān fragments were discovered in a walled-up attic of the Great Mosque of Ṣanʿāʾ, more precisely since 2004, when Sergio Noga Noseda was allowed to produce high-resolution colour photographs, since scholars have recognised that leaves kept in up to seven different collections formed one codex and that they can be studied thanks to online and printed publications.

Since thousands of short texts carved in stone from Syria, Jordan and Sa'udi Arabia can be read (ever better), research into the Arabic language and script of the centuries immediately before and after Muḥammad has been the most exciting part of Islamic studies.

Since the destruction of the Twin Towers in Manhattan, reflections on Islam as a late ancient civilisation and/or religion related to Judaism and Christianity have been particularly popular.

Unfortunately, experts in these interesting fields also comment on a subject they have not studied ‒ because it is not interesting enough - and write almost nothing but nonsense about it.

The field of printed editions of the Qur'an needs to be cleaned up. And that is what I want to do here. Many German Orientalists refer to the official Egyptian edition of 1924/5 as "the standard Qur'an", others call it "Azhar Qur'an". Some call it "THE Cairo Edition/CE" ‒ utter nonsense. Many false ideas circulate about the King Fuʾād edition, the Giza Qur'an, the Egyptian Survey Authority print (المصحف الشريف لطبعة مصلحة المساحة المصرية), the 12-liner (مصحف 12 سطر). Some believe they are looking at a manuscript, Andreas Ismail Mohr and Prof. Dr. Murks call it "type printing". Yet the epilogue ‒ from 1926 even more clearly than the first one (1924/5) ‒ makes everything clear: The book written by Egypt's šaiḫ al-maqāriʾ Muḥammad ibn ʿAlī ibn Ḫalaf al-Ḥusainī al-Mālikī aṣ-Ṣaʿīdī al-Ḥaddād (1282/1865-1357/ 22.1. 1939) ‒ not to be confused with the calligrapher Muḥammad ibn Saʿd ibn Ibrāhīm al-Ḥaddād (1919-2011) ‒ was set in Būlāq with five tiers per line (pause signs; fatḥa, damma, sukūn; letters [for baseline hamza including the vowel sign]; kasra; spacing).

added later: If you want to see/understand what was made "between Būlāq and Giza"/between type setting and printing" have a look at the Hyderabad print of 1938: they used the same sorts/metal types but not not "lift" kasra, resulting in a less clear lines.These were made into printing plates in Giza ‒ where they already had experience with printing maps in offset. Printing was also done there.

for the latestest on the King Fuʾād Edition

Type printing is a letterpress process. The types/sorts leave small indentations on the paper: the types/sorts press the printing ink into the paper. Offset is planographic: the paper absorbs the ink; you can't find indentations. With his eyes, Mohr saw that it was not handwritten. But he does not know that type print can only be recognised with the sense of touch (not by vision). And neither did Prof. Dr. Murks.

"That's nonsense, instead of elaborately typesetting and printing that ONCE, why not have a calligrapher write it?" This fails to appreciate the technoid sense of accuracy of the editors of 1924. To this day, there is no one except ʿUṯmān Ṭaha (UT) who is as accurate as the typesetting or the computer.

Two examples to illustrate.

While UT clearly reads yanhā, the beautiful Ottoman handwriting reads naihā; while the three vowel signs (fatḥa, sukūn, Lang-ā) are clearly in the right order (there is no other way, they are all on top), nūn (perhaps) comes before yāʾ (does the nūn dot come before the yāʾ dots). Incidentally, the two "tooth" letters have a tooth or spine in UT, but none in court Ottoman! While there is clearly nothing between heh (I use the Unicode name to clearly distinguish it from ḥāʾ) and alif maqṣūra in UT, there could well be a tooth in Ottoman: You only needed to put two dots over it and it would be hetā or something like that.

Second example: wa-malāʾikatihī Whereas in the 1924/5 Qur'an (below) and UT (in the middle) there is a substitute alif-with-madda hovering BEFORE the tooth above the baseline, in Muṣḥaf Qaṭar (above) there is a hamza-kasra hovering AFTER the change alif-with-madda below the baseline, which changes the yāʾ-tooth into a (lengthening) alif. There is nothing wrong with this (sound and rasm are the same, after all), but it is a different orthography and should not be, according to the conception of people who do not tolerate any approximation in the Qur'an.

Now the whole of page 3 in comparison. Giza print and UT: the Amiriyya is more calligraphic than UT, which can be seen in the examples in the right margin.

All in all, UT follows the default. Baseline and clear from right to left. Only in the spacing between words is it less modern than the Amiriyya (which is why Dar al-Maʿrifa increased the spacing).

Also from page 3 Comparison of Muṣḥaf Qaṭar and UT. In the first and last examples, Abū ʿUmar ʿUbaidah Muḥammad Ṣāliḥ al-Banki / عبيدة محمد صالح البنكي does not place the yāʾ-dots EXACTLY under the tooth (in the first case because of the close nūn, in the second case without need). Three cases show tooth letters without a tooth. And a cuddle-mīm, which makes its vowel sign sit wrong (for modern readers): the mīm is to the right of the lām, but the mīm vowel sign is to the left, because the mīm is to be pronounced after the lām. So it is rightly "wrong".

Before I stop (for today): a map of Cairo 1920, on which I have marked the Amiriyya and the Land Registry with arrows in the Nil, as well as Midan Tahrir and the place where the government printing press is now located. Also the Ministry of Education and the Nāṣirīya, where three of the signatories of the afterword worked.

Everything to the right of the Nile plus the islands is Cairo, everything to the left (Imbaba, Doqqi, Giza) not only does not belong to the city of Cairo, but is in another province.

Important: the typesetting workshop and the offset workshop were well connected by car, tram and boat. The assembled pages did not have a long way to go.

The two Arabic texts are the 1924 and 1952 printer's notes, both from the copies in the Prussian State Library, which owns five editions. And here is the very last (unpaginated) page of the original print.

"al-Qāhira" has to wait till the Fifties to appear.

"al-Qāhira" has to wait till the Fifties to appear.

Before I stop (for today): a map of Cairo 1920, on which I have marked the Amiriyya and the Land Registry with arrows in the Nil, as well as Midan Tahrir and the place where the government printing press is now located. Also the Ministry of Education and the Nāṣirīya, where three of the signatories of the afterword worked.

Everything to the right of the Nile plus the islands is Cairo, everything to the left (Imbaba, Doqqi, Giza) not only does not belong to the city of Cairo, but is in another province.

Important: the typesetting workshop and the offset workshop were well connected by car, tram and boat. The assembled pages did not have a long way to go.

The two Arabic texts are the 1924 and 1952 printer's notes, both from the copies in the Prussian State Library, which owns five editions. And here is the very last (unpaginated) page of the original print.

"al-Qāhira" has to wait till the Fifties to appear.

"al-Qāhira" has to wait till the Fifties to appear.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Nairīzī

Mirza Aḥmad an-Nairīzī (ca. 1650–1747) is the last of the classical Iranian calligraher s. Informations are hard to find, because often und...

-

There are several types of madd sign in the Qurʾān, in South Asian masāhif: madd al-muttasil for a longer lengthening of the vowel used...

-

40 years ago Adrian Alan Brockett submitted his Ph.D. to the University of St.Andrews: Studies in Two Transmissions of the Qurʾān . Now...

-

Although it is often written that the King Fuʾād Edition fixed a somehow unclear text, and established the reading of Ḥafṣ according to ʿĀ...