Showing posts with label offset. Show all posts

Showing posts with label offset. Show all posts

Friday, 15 November 2024

KFE <--> kfe

While IDEO held a conference on "100 years of the Cairo Edition" without having a single copy

‒ either of the 1924 edition by al-Ḥusainī al-Ḥaddād nor the 1952 one by aḍ-Ḍabbāʿ & colleagues, neither a big one, nor a small one,

not even a version by a commercial or foreign publisher, just a 1971 print of the 1952 text on 548 pages with 15 lines per page.

Both the Berlin Staatsbiblothek

and Muhammad Hozien

have severval copies.

top image: editions of 1924/5 and 1927, below: both from 1952.

While the Staatsbibliothek was just lucky (getting an intact copy of 1952 with the dedication to King Fuʾād [from East-Berlin] and one in which

the republican bookseller had torn out the page [from West-Berlin]), Muhammad Hozien searched, because he knew that they are not just prints of the same.

1924 to 1952 it is fairly easy:

First comes KFE_1,

then kfe_a, kfe_b, kfe_c

‒ a succession, a development: each edition builds on the earlier one.

When exactely these four editions were published I do not know:

the problem for KFE_1 is objective, for the small ones only subjective (I did not pay sufficient addention).

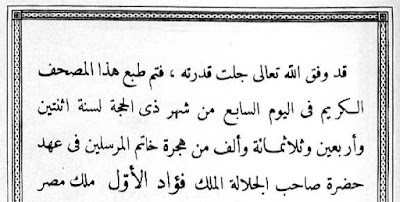

In all editions up to 1952 one can read:

Printing was finished 7. Ḏul Ḥigga 1342 (= 10.7. 1924).

I have a problem:

How can the book with that text inside know when its printing was finished?

Was it observing its own printing and taking the time?

I guess (!) that the date given was just the date planned,

and because they could not meet it, they decided to stamp the finished book with the real date:

The differences between the editions before 1952 are minor.

My main conclusion from studying the text of 1242/43:

it is not the result of year long committee discussions,

nor the application of what ad-Dānī and Ibn Naǧǧāḥ have written about the rasm,

but a switch form Indian-Persian-Ottoman practise of writing the well established text of Ḥafṣ

to applying the African (Maġribian, Andalusian) rules (without clolour dots, too expensice/complicated for printing at the time).

The text the type setters set &npsp; was written by the chief reader of Egypt, Muḥammad ibn ʿAlī ibn Ḫalaf al-Ḥusainī al-Mālikī aṣ-Ṣaʿīdī al-Ḥaddād (born 1282/1865)

who knew the differences between Warš (of which he had a copy at hand) and Ḥafṣ by heart.

After he had died on 22.1.1939, ʿAlī b. Muḥammad b. Ḥasan b. Ibrāhīm al-Maṣrī aḍ-Ḍabbāʿ became chief reciter of the qurʾān.

He chaired a committee to revise the written text. Apart of one clear mistake (the spelling of /kalimat/ in 7:137), some minor corrections, the elimination of information on the chronology in the sura title boxes, the inclusion of the basmalla in continuous reading (which leads to tanwīn becoming tamwīm at the end of suras 4, 5, 6, 17, 18, 19, 24, 25, 31, 33, 34, 35, 38, 41, 48, 54, 65, 67, 71, 72, 73, 76, 78, 84, 85, 86, 90, 100, 101, 104, 105, 106, and 110)

and about 800 changes in pause signs were decreed ‒ decreed, not made, because the changes were only made in the large editions, for which new plates were manufactured. For the small editions old plates were used, and here some changes were just not made, others by hand. Only the changes in tanwin were all made. (on the image in the middle from the 1954 small edition the sura title box is the old one and the mīm added by hand

below from the Tashkent 1960 reprint.)

so we have: KFE_1 less than 1000 changges in KFE_2 /2a

but: kfe1345, kfe1347 ; less than 100 changes in kfe1371 based on kfe1347 except for the nūn in 73:20

And the changes introduced in kfe1345 and kfe1347 are all gone in KFE_2;

BECAUSE they never occured on the large plates ‒ existing plates were reused.

So, there are technical reasons for the content of the different editions.

While for the Muṣḥaf al-Azhar aš-Šarīf, "the Šamarlī" and the Madina Editions

we have different sizes of the same content,

while we have huge runs of Madina Editions, hence fresh plates (almost) evey year,

the runs of King Fuʾād Editions were low, so low that some of the 1924 plates were used until the end, and some of the first small plates from the next year to the end.

‒

Saturday, 8 August 2020

Kabul 1352 /1934

Gizeh 1924 is important because,

‒ with it Egypt by and large switched to the Maġribian rasm ‒ roughly Ibn Naǧāḥ,

‒ switched to the Maġribian way of writing long vowels, signalling muteness,

differenciating between three forms of tanwīn, but having one form of madd-sign only

‒ the afterword explained the principles of the edition

like in the Lucknow editions since the 1870s and the Muxalallātī lithographiy of 1890

‒ there was extra space between words and there were few ligatures,

base line oriented

‒ the text was type set, printed once; the print was adjusted before plates are made for offset printing.

The new orthography is quickly adopted by private Egyptian printers, in the mašriq only after 1980.

Šamarlī and the new ʿUṯmān Ṭāhā editions have almost no space between words,

while most newer Turkish maṣāḥif separte the words.

while most newer Turkish maṣāḥif separte the words.

There is just one muṣḥaf that is type set and offset printed

‒ just like Gizeh 1924. It went largely unnoticed:

Kabul 1352/1934

There is just one muṣḥaf that is type set and offset printed

‒ just like Gizeh 1924. It went largely unnoticed:

Kabul 1352/1934

Gizeh 1924 and Kabul 1934 side by side.

Gizeh 1924 and Kabul 1934 side by side.

Gizeh 1924 and Kabul 1934 side by side.

Gizeh 1924 and Kabul 1934 side by side.

Sunday, 10 March 2019

The Ḥafṣ ʿan ʿĀṣim King Fuʾād 1924/5 edition

I have just published an essay on Qurʾān prints on Amazon:

I want to blog about that and from it here.

(this is my German post translated by deepl)

In the course of time I will probably bring everything from the book - but slowly...

Since 1972, when thousands of very old Qurʾān fragments were discovered in a walled-up attic of the Great Mosque of Ṣanʿāʾ, more precisely since 2004, when Sergio Noga Noseda was allowed to produce high-resolution colour photographs, since scholars have recognised that leaves kept in up to seven different collections formed one codex and that they can be studied thanks to online and printed publications.

Since thousands of short texts carved in stone from Syria, Jordan and Sa'udi Arabia can be read (ever better), research into the Arabic language and script of the centuries immediately before and after Muḥammad has been the most exciting part of Islamic studies.

Since the destruction of the Twin Towers in Manhattan, reflections on Islam as a late ancient civilisation and/or religion related to Judaism and Christianity have been particularly popular.

Unfortunately, experts in these interesting fields also comment on a subject they have not studied ‒ because it is not interesting enough - and write almost nothing but nonsense about it.

The field of printed editions of the Qur'an needs to be cleaned up. And that is what I want to do here. Many German Orientalists refer to the official Egyptian edition of 1924/5 as "the standard Qur'an", others call it "Azhar Qur'an". Some call it "THE Cairo Edition/CE" ‒ utter nonsense. Many false ideas circulate about the King Fuʾād edition, the Giza Qur'an, the Egyptian Survey Authority print (المصحف الشريف لطبعة مصلحة المساحة المصرية), the 12-liner (مصحف 12 سطر). Some believe they are looking at a manuscript, Andreas Ismail Mohr and Prof. Dr. Murks call it "type printing". Yet the epilogue ‒ from 1926 even more clearly than the first one (1924/5) ‒ makes everything clear: The book written by Egypt's šaiḫ al-maqāriʾ Muḥammad ibn ʿAlī ibn Ḫalaf al-Ḥusainī al-Mālikī aṣ-Ṣaʿīdī al-Ḥaddād (1282/1865-1357/ 22.1. 1939) ‒ not to be confused with the calligrapher Muḥammad ibn Saʿd ibn Ibrāhīm al-Ḥaddād (1919-2011) ‒ was set in Būlāq with five tiers per line (pause signs; fatḥa, damma, sukūn; letters [for baseline hamza including the vowel sign]; kasra; spacing).

Type printing is a letterpress process. The types/sorts leave small indentations on the paper: the types/sorts press the printing ink into the paper. Offset is planographic: the paper absorbs the ink; you can't find indentations. With his eyes, Mohr saw that it was not handwritten. But he does not know that type print can only be recognised with the sense of touch (not by vision). And neither did Prof. Dr. Murks.

"That's nonsense, instead of elaborately typesetting and printing that ONCE, why not have a calligrapher write it?" This fails to appreciate the technoid sense of accuracy of the editors of 1924. To this day, there is no one except ʿUṯmān Ṭaha (UT) who is as accurate as the typesetting or the computer.

Two examples to illustrate.

While UT clearly reads yanhā, the beautiful Ottoman handwriting reads naihā; while the three vowel signs (fatḥa, sukūn, Lang-ā) are clearly in the right order (there is no other way, they are all on top), nūn (perhaps) comes before yāʾ (does the nūn dot come before the yāʾ dots). Incidentally, the two "tooth" letters have a tooth or spine in UT, but none in court Ottoman! While there is clearly nothing between heh (I use the Unicode name to clearly distinguish it from ḥāʾ) and alif maqṣūra in UT, there could well be a tooth in Ottoman: You only needed to put two dots over it and it would be hetā or something like that.

Second example: wa-malāʾikatihī Whereas in the 1924/5 Qur'an (below) and UT (in the middle) there is a substitute alif-with-madda hovering BEFORE the tooth above the baseline, in Muṣḥaf Qaṭar (above) there is a hamza-kasra hovering AFTER the change alif-with-madda below the baseline, which changes the yāʾ-tooth into a (lengthening) alif. There is nothing wrong with this (sound and rasm are the same, after all), but it is a different orthography and should not be, according to the conception of people who do not tolerate any approximation in the Qur'an.

Now the whole of page 3 in comparison. Giza print and UT: the Amiriyya is more calligraphic than UT, which can be seen in the examples in the right margin.

All in all, UT follows the default. Baseline and clear from right to left. Only in the spacing between words is it less modern than the Amiriyya (which is why Dar al-Maʿrifa increased the spacing).

I want to blog about that and from it here.

(this is my German post translated by deepl)

In the course of time I will probably bring everything from the book - but slowly...

Since 1972, when thousands of very old Qurʾān fragments were discovered in a walled-up attic of the Great Mosque of Ṣanʿāʾ, more precisely since 2004, when Sergio Noga Noseda was allowed to produce high-resolution colour photographs, since scholars have recognised that leaves kept in up to seven different collections formed one codex and that they can be studied thanks to online and printed publications.

Since thousands of short texts carved in stone from Syria, Jordan and Sa'udi Arabia can be read (ever better), research into the Arabic language and script of the centuries immediately before and after Muḥammad has been the most exciting part of Islamic studies.

Since the destruction of the Twin Towers in Manhattan, reflections on Islam as a late ancient civilisation and/or religion related to Judaism and Christianity have been particularly popular.

Unfortunately, experts in these interesting fields also comment on a subject they have not studied ‒ because it is not interesting enough - and write almost nothing but nonsense about it.

The field of printed editions of the Qur'an needs to be cleaned up. And that is what I want to do here. Many German Orientalists refer to the official Egyptian edition of 1924/5 as "the standard Qur'an", others call it "Azhar Qur'an". Some call it "THE Cairo Edition/CE" ‒ utter nonsense. Many false ideas circulate about the King Fuʾād edition, the Giza Qur'an, the Egyptian Survey Authority print (المصحف الشريف لطبعة مصلحة المساحة المصرية), the 12-liner (مصحف 12 سطر). Some believe they are looking at a manuscript, Andreas Ismail Mohr and Prof. Dr. Murks call it "type printing". Yet the epilogue ‒ from 1926 even more clearly than the first one (1924/5) ‒ makes everything clear: The book written by Egypt's šaiḫ al-maqāriʾ Muḥammad ibn ʿAlī ibn Ḫalaf al-Ḥusainī al-Mālikī aṣ-Ṣaʿīdī al-Ḥaddād (1282/1865-1357/ 22.1. 1939) ‒ not to be confused with the calligrapher Muḥammad ibn Saʿd ibn Ibrāhīm al-Ḥaddād (1919-2011) ‒ was set in Būlāq with five tiers per line (pause signs; fatḥa, damma, sukūn; letters [for baseline hamza including the vowel sign]; kasra; spacing).

added later: If you want to see/understand what was made "between Būlāq and Giza"/between type setting and printing" have a look at the Hyderabad print of 1938: they used the same sorts/metal types but not not "lift" kasra, resulting in a less clear lines.These were made into printing plates in Giza ‒ where they already had experience with printing maps in offset. Printing was also done there.

for the latestest on the King Fuʾād Edition

Type printing is a letterpress process. The types/sorts leave small indentations on the paper: the types/sorts press the printing ink into the paper. Offset is planographic: the paper absorbs the ink; you can't find indentations. With his eyes, Mohr saw that it was not handwritten. But he does not know that type print can only be recognised with the sense of touch (not by vision). And neither did Prof. Dr. Murks.

"That's nonsense, instead of elaborately typesetting and printing that ONCE, why not have a calligrapher write it?" This fails to appreciate the technoid sense of accuracy of the editors of 1924. To this day, there is no one except ʿUṯmān Ṭaha (UT) who is as accurate as the typesetting or the computer.

Two examples to illustrate.

While UT clearly reads yanhā, the beautiful Ottoman handwriting reads naihā; while the three vowel signs (fatḥa, sukūn, Lang-ā) are clearly in the right order (there is no other way, they are all on top), nūn (perhaps) comes before yāʾ (does the nūn dot come before the yāʾ dots). Incidentally, the two "tooth" letters have a tooth or spine in UT, but none in court Ottoman! While there is clearly nothing between heh (I use the Unicode name to clearly distinguish it from ḥāʾ) and alif maqṣūra in UT, there could well be a tooth in Ottoman: You only needed to put two dots over it and it would be hetā or something like that.

Second example: wa-malāʾikatihī Whereas in the 1924/5 Qur'an (below) and UT (in the middle) there is a substitute alif-with-madda hovering BEFORE the tooth above the baseline, in Muṣḥaf Qaṭar (above) there is a hamza-kasra hovering AFTER the change alif-with-madda below the baseline, which changes the yāʾ-tooth into a (lengthening) alif. There is nothing wrong with this (sound and rasm are the same, after all), but it is a different orthography and should not be, according to the conception of people who do not tolerate any approximation in the Qur'an.

Now the whole of page 3 in comparison. Giza print and UT: the Amiriyya is more calligraphic than UT, which can be seen in the examples in the right margin.

All in all, UT follows the default. Baseline and clear from right to left. Only in the spacing between words is it less modern than the Amiriyya (which is why Dar al-Maʿrifa increased the spacing).

Also from page 3 Comparison of Muṣḥaf Qaṭar and UT. In the first and last examples, Abū ʿUmar ʿUbaidah Muḥammad Ṣāliḥ al-Banki / عبيدة محمد صالح البنكي does not place the yāʾ-dots EXACTLY under the tooth (in the first case because of the close nūn, in the second case without need). Three cases show tooth letters without a tooth. And a cuddle-mīm, which makes its vowel sign sit wrong (for modern readers): the mīm is to the right of the lām, but the mīm vowel sign is to the left, because the mīm is to be pronounced after the lām. So it is rightly "wrong".

Before I stop (for today): a map of Cairo 1920, on which I have marked the Amiriyya and the Land Registry with arrows in the Nil, as well as Midan Tahrir and the place where the government printing press is now located. Also the Ministry of Education and the Nāṣirīya, where three of the signatories of the afterword worked.

Everything to the right of the Nile plus the islands is Cairo, everything to the left (Imbaba, Doqqi, Giza) not only does not belong to the city of Cairo, but is in another province.

Important: the typesetting workshop and the offset workshop were well connected by car, tram and boat. The assembled pages did not have a long way to go.

The two Arabic texts are the 1924 and 1952 printer's notes, both from the copies in the Prussian State Library, which owns five editions. And here is the very last (unpaginated) page of the original print.

"al-Qāhira" has to wait till the Fifties to appear.

"al-Qāhira" has to wait till the Fifties to appear.

Before I stop (for today): a map of Cairo 1920, on which I have marked the Amiriyya and the Land Registry with arrows in the Nil, as well as Midan Tahrir and the place where the government printing press is now located. Also the Ministry of Education and the Nāṣirīya, where three of the signatories of the afterword worked.

Everything to the right of the Nile plus the islands is Cairo, everything to the left (Imbaba, Doqqi, Giza) not only does not belong to the city of Cairo, but is in another province.

Important: the typesetting workshop and the offset workshop were well connected by car, tram and boat. The assembled pages did not have a long way to go.

The two Arabic texts are the 1924 and 1952 printer's notes, both from the copies in the Prussian State Library, which owns five editions. And here is the very last (unpaginated) page of the original print.

"al-Qāhira" has to wait till the Fifties to appear.

"al-Qāhira" has to wait till the Fifties to appear.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Nairīzī

Mirza Aḥmad an-Nairīzī (ca. 1650–1747) is the last of the classical Iranian calligraher s. Informations are hard to find, because often und...

-

There are several types of madd sign in the Qurʾān, in South Asian masāhif: madd al-muttasil for a longer lengthening of the vowel used...

-

40 years ago Adrian Alan Brockett submitted his Ph.D. to the University of St.Andrews: Studies in Two Transmissions of the Qurʾān . Now...

-

Although it is often written that the King Fuʾād Edition fixed a somehow unclear text, and established the reading of Ḥafṣ according to ʿĀ...