There is only one qur'ān.

But there are many differences in the editions.

‒ differences in the style of writing, the graphic form

‒ different divisions (verses,

manāzil, aḥzāb, pages ...)

BTW: the suras and their order are the same in all editions,

but their names can be different,

the information given in the Header can be different,

‒ differences in the words, the sound of the qurʾān, the (micro)meaning ‒

this is meant with the ten canonical readings,

the twenty transmissions, the four additional

(less canonical) readings plus all the variants that are not recognized.

HERE I do not talk about the recitation style, nor about the (national) accents of recitors,

but just about

‒ differences in the letters, writing of the words = the

rasm,

‒ differences in the additional signs for vowells, doubeling,

extra length, silence, required response.

When you multiply all of these, there are thousands of possibilities.

You might say, but when one writes in Fāsī style, it is the transmission of Warš,

the

rasm of Ḫarrāz with Maġribian subdivisions and additonal signs, Medinese verse endings.

Yes, very likely, but not certain.

Here images from two printed Tunisian editions

of the transmission of Ḥafṣ written in Maġribī style:

If you a sceptical and lazy, here is mālik from the Fatiḥa with /ā/ red added alif:

And here the one verse where Ḥafs allows both fatḥa (black) and ḍamma (red): /ḍaffin/, /ḍuffin/

And when you think, that for the

rasm there are five, six or maybe ten possibilities, you are wrong.

When you write a

muṣḥaf (or prepare a printing) you do not have to stick to one authority.

You are free to write one word (even a word at one particular place) with a vowel letter or without.

The King Fahd Complex has adopted the

rasm of the Qahira1952 Edition (which is rather obscure) changed

one word (in 2:72), Qaṭar has changed another word

(in 56:2). Indonesia (Ministry of Religious Affairs) and Iran (the Center for the Printing and Distribution of the Holy Quran) have made wild choices ‒ at least these are documented (albeit not in the

muṣḥaf).

BTW, I called Q52 obscure, because it does itself not stick to an authority. Therefore careful editors have added "mostly"/ġāliban or "in the most"/fil ġālib to the statement made in the afterword, that the

rasm is according to Ibn Naǧāḥ.

So millions of different ‒ equally valid ‒ editions are possible, thousands do exist.

I am mainly interested in orthography:

i.e. the list of the written words ‒ but unlike

Webster or

Le Dictionaire de l'Académie Franҫaise a word can be written differently at different places

(سِيمَىٰهُمۡ (7:48

(2:273, 47:40, 55:41) سِيمَـٰهُمۡ

(سِيمَاهُمۡ (48:29

The German expert for Qurʾānic paleo-orthography, who has studied the old mss.

‒ Diem has "just" studied the Nabataen precursor ‒

is convinced that

first the yāʾ was used for writing the /ā/,

then nothing,

before the modern strategy ‒ using an

alif ‒ became common.

I do not give his name because I have to critize him strongly:

Although quoting the text of the Gizeh Qurʾān (1924/Būlāq 1952), which he calls "The Standard Text",

he uses a dotted

yāʾ where Gizeh uses an undotted one,

and he uses the circle for sukûn, where Gizeh uses the Indian (by now Qurʾānic)

Jazm-sign.

He does not see that graphic style, divisions,

rasm writing, and the way of voweling are independent of each each.

what I have shown above.

Or even more to the point:

the differences in sounds (the

qiraʾāt) reflected in very few differences in the

rasm,

in few cases by different diacritical points,

but mainly by

hamza sign,

šadda and vowel signs

and most

rasm differences (differences in writing long vowels)

are two separate things.

Just because the only edition of the transmission of Qālūn according to Nāfiʿ he owns,

follows the

rasm described by ad-Dānī in the

Muqnī,

he calls that

rasm "the Qālūn

rasm",

he takes the delivery boy for the pizza backer.

Okay, I went too far.

Between Kufa (Ḥafṣ and five others) and Medina (Warš and Qālūn) there are 30 differences in the rasm.

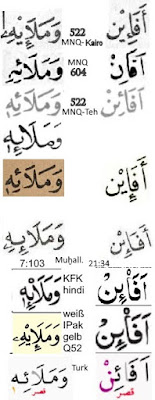

When you look at the beginning of 46:15 in my pictures, there are two differences:

aḥsana(n) vs. ḥusna(n); this is a difference in sound, a difference between qiraʾāt, and

insān written with alif or without (i.e. with substitution alif = dagger alif = small alif = quṣair);

this is a difference in writing only, a difference in the rasm.

The three last lines are all the transmission of Qālūn, the last but three with the Dānī-rasm,

the two at the very bottom with Ibn Naǧāḥ's rasm,

which is common for Warš and Qālūn ‒ except for the edition pushed by Qaḏḏāfī ‒ and is used for Ḥafṣ since 1924 (common by now).

There are a few thousand difference in words/sound/local meaning ‒ rarely changing great things.

There are a few thousand difference in writing ‒ not affecting the sound/words/meaning at all.

Qālūn vs. Ḥafs belongs to the first category,

rasm writing (according to ad-Dānī or al-Arkātī or based on nine good editions) on the second.

And there is a little overlap: 30 differences in the rasm reflecting differences in the "readings".

but the Qālūn muṣḥaf the expert had in his hand is now called muṣḥaf ad-Dānī, because that's what sets it apart, not the reading.

Here Turks (last line) have the same silent alif; they shorten it, i.e. the fatḥa is valid, the alif is not.

BTW: In one of the three maṣāḥif of Muṣṭafā Naẓīf the yāʾ is missing -> the alif carries the hamza+kasra (first line on the right side).

Here Turks (last line) have the same silent alif; they shorten it, i.e. the fatḥa is valid, the alif is not.

BTW: In one of the three maṣāḥif of Muṣṭafā Naẓīf the yāʾ is missing -> the alif carries the hamza+kasra (first line on the right side).

Here Turks (first line) actually have an otisose alif LESS (END of my snippet)

What these experts want to say:

There are more Alif Matres lectionis, i.e. alifs standing for /a/.

Here Turks (first line) actually have an otisose alif LESS (END of my snippet)

What these experts want to say:

There are more Alif Matres lectionis, i.e. alifs standing for /a/.