Showing posts with label Petersburg. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Petersburg. Show all posts

Monday, 29 July 2024

St. Petersburg 1787

The first print by and for Muslims (with the help of Muslims by Russians) was paid by Catharina II.

Here as always in the blog (and on other sites) first click on the bad images than choose (after left-click in windows, alt-click on the Mac) "open link in new tab" (not:"open image..."), possible "+" (plus) et voilà

This blog is called "no standard", i.e. many standards, no single standard:

numerically the most important standard is the Indo-Pakistani or Eastern standard (with slight variants in Bombay, Kerala, Bengal ...),

among Orientalists and since about 1980 the standard among Arabs and Malaysia is the Western/Maghrebian/Andalusian/Giza24-Cairo52 standard;

where I am (Berlin) the Turkish standard (based on Ottoman practice) is important,

the most populous Muslim country has a standard of its own,

Persian and modern Iranian standards are (like Ottoman ones) based on the Indian one.

As we will see now the Russian-Tartarian standard is similar to the Turkish one.

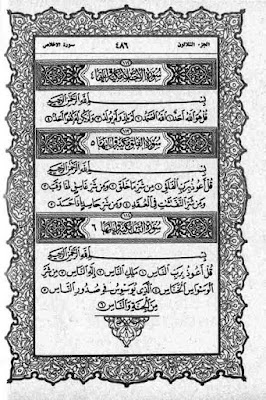

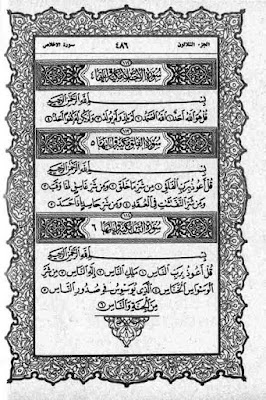

The images show the beginning of the Qurʾān first in the Modern Arab Standard, the IndoPak, the Turkish and than the Russian:

as in the first part of verse 7 the long-ā of /ʿalā/ is marked by a madda,

I added this part from two Kazan prints (1880 and 2000) in which this particularity is normalized:

(Note: In verse 10 happened what was mentioned earlier: the personal pronoun that is part of the word فَزَادَهُمُ is put on the next line.)

now the first line of the next page ‒ because it has the first /lahū/ that is not written with a wau; long-ū is marked in the first two examples, but not in the Turkish, nor in the

Russian print:

Here two pages corrected according to the list of errors published in the print:

I have been asked about complete sets of scans of St.Petersburg prints.

So here are four more pages from two different scans:

‒

Sunday, 30 May 2021

The Pope, The Cairo Edition

Among Catholics one may speak of "the pope", among "normal" people one SHOULD say "the Roman pope", "the pope of the Occident", "the bishop of Rome", because ‒ leaving metaphorical use aside ‒ there are two more popes: the Coptic and the Greek "bishof of Alexandria and all Africa" in Cairo ((the bishops of Antiochia and All the Orient are not styled as pope)). What is common knowledge among Egyptian Christians is unknown to many people in the States or in the UK.

Unlike popes, of which there are only three at a time, there are literaly thousand Cairo editions of the qurʾān. But some young scholars write of "The Cairo Edition". Out of ignorance or stupitity? Maybe they do not know the difference between "a" and "the" ... When I alerted one, s/he added "colloquially known", an other just shrugged h*r/s shoulders, a third admitted that s/he has never looked into another muṣḥaf ‒ although as Professor of Islamic Studies s/he should have been to a mosque and/or an islamic bookshop and opened a muṣḥaf used by local Muslims (and they certainly do NOT use the KFE/King Fuʾād Edition = idiot's "CE"!)

Sometimes one sees "the St. Petersburg edition of the Qurʾān". I do not know how many editions exist ‒ certainly not just one: First we know of editions in 1787, 1789, 1790, 1793, 1796 and 1798. Copies of these six editions have no year on the title page or in the backmatter ... ... so one could treat them as one: the 1787-98 Mollah Ismaʿīl ʿOsman St. Petersburg edition: Because there are more, like the 1316/1898 Muṣṭafā Naẓīf Qadirġalī St. Petersburg edition Note the title: Kalām Qadīm

which does not refer to an antique shop, to antiquarian,

but to the pre-existence of the kalāmullāh ὁ λόγος "THE St.Petersburg" edition is illogical. Only ignorant or stupid people use that expression. (Of course some are ignorant, stupid AND amoral.))

Unlike popes, of which there are only three at a time, there are literaly thousand Cairo editions of the qurʾān. But some young scholars write of "The Cairo Edition". Out of ignorance or stupitity? Maybe they do not know the difference between "a" and "the" ... When I alerted one, s/he added "colloquially known", an other just shrugged h*r/s shoulders, a third admitted that s/he has never looked into another muṣḥaf ‒ although as Professor of Islamic Studies s/he should have been to a mosque and/or an islamic bookshop and opened a muṣḥaf used by local Muslims (and they certainly do NOT use the KFE/King Fuʾād Edition = idiot's "CE"!)

Sometimes one sees "the St. Petersburg edition of the Qurʾān". I do not know how many editions exist ‒ certainly not just one: First we know of editions in 1787, 1789, 1790, 1793, 1796 and 1798. Copies of these six editions have no year on the title page or in the backmatter ... ... so one could treat them as one: the 1787-98 Mollah Ismaʿīl ʿOsman St. Petersburg edition: Because there are more, like the 1316/1898 Muṣṭafā Naẓīf Qadirġalī St. Petersburg edition Note the title: Kalām Qadīm

which does not refer to an antique shop, to antiquarian,

but to the pre-existence of the kalāmullāh ὁ λόγος "THE St.Petersburg" edition is illogical. Only ignorant or stupid people use that expression. (Of course some are ignorant, stupid AND amoral.))

Saturday, 10 April 2021

Efim Rezvan: Orthography in EQ3

The editors of Brill's Encyclopedia of the Quran thought it wise to let Efim Rezvan write an article, unfortunately about a subject, he did not master.

I just want to point out some of the mistakes:

"Arabic writing at that time conveyed only consonants"

As I have shown, Arabic at the time had just letters, that could stand for consonants and vowels.

"..., which permitted a shift from a scriptio defectiva to a scriptio plena."

Although Rezvan does not say it explicitly ‒ nor does he state the contrary ‒, he gives the impression that the early manuscripts had no diactrics, nor vowel signs. But ALL early manuscripts has SOME diacritics and vowel (and hamza) signs.

"al-Ḥajjāj [introduced] a system to designate long and short vowels"

Since we still do not have ONE system to designate ALL long and ALL short vowels, I'd like to read more about the system of the 8th century.

"In practice only two of the systems noted by Ibn Mujāhid became widespread: the Kūfan, Ḥafṣ (d. 246⁄860) ʿan ʿĀṣim (d. 127⁄744), and, to a lesser degree, the Medinan, Warsh (d. 197⁄812) ʿan Nafiʿ (d. 169⁄785)."

just wrong. That TODAY only four systems are widely used ‒ of which he mentioned only two ‒ does NOT mean AT ALL, that at Ibn Mujāhid (245-324/859-935)'s time or in the following centuries 12 of his 14 riwāyāt were hardly used. The opposite is true: more than his fourteen were used.

"It is possible that [the St.Petersburg/Kazan] edition played a decisive role in the centuries-long process of standardizing qurʾānic orthography."

"The final stage of the work on the unification of the qurʾānic text is connected with the appearance in Cairo in 1342⁄ 1923-4 of a new edition of the text"

nonsense

it was "Drawn up by a special panel of Muslim scholars"

nonsense, it was ONE man, Egypt's main recitor of the qurʾān (šayḫ al-maqāriʾ al-miṣrīya)

"today accepted throughout the Muslim world"

just wrong.

"in Zaydī Yemen, traditions remain which go back to a different transmitter of the text, Warsh."

it seems that Yamanī Zaydīs read Qālūn

The last two paragraphes are gibberish.

I just want to point out some of the mistakes:

"Arabic writing at that time conveyed only consonants"

As I have shown, Arabic at the time had just letters, that could stand for consonants and vowels.

"..., which permitted a shift from a scriptio defectiva to a scriptio plena."

Although Rezvan does not say it explicitly ‒ nor does he state the contrary ‒, he gives the impression that the early manuscripts had no diactrics, nor vowel signs. But ALL early manuscripts has SOME diacritics and vowel (and hamza) signs.

"al-Ḥajjāj [introduced] a system to designate long and short vowels"

Since we still do not have ONE system to designate ALL long and ALL short vowels, I'd like to read more about the system of the 8th century.

"In practice only two of the systems noted by Ibn Mujāhid became widespread: the Kūfan, Ḥafṣ (d. 246⁄860) ʿan ʿĀṣim (d. 127⁄744), and, to a lesser degree, the Medinan, Warsh (d. 197⁄812) ʿan Nafiʿ (d. 169⁄785)."

just wrong. That TODAY only four systems are widely used ‒ of which he mentioned only two ‒ does NOT mean AT ALL, that at Ibn Mujāhid (245-324/859-935)'s time or in the following centuries 12 of his 14 riwāyāt were hardly used. The opposite is true: more than his fourteen were used.

"It is possible that [the St.Petersburg/Kazan] edition played a decisive role in the centuries-long process of standardizing qurʾānic orthography."

"The final stage of the work on the unification of the qurʾānic text is connected with the appearance in Cairo in 1342⁄ 1923-4 of a new edition of the text"

nonsense

it was "Drawn up by a special panel of Muslim scholars"

nonsense, it was ONE man, Egypt's main recitor of the qurʾān (šayḫ al-maqāriʾ al-miṣrīya)

"today accepted throughout the Muslim world"

just wrong.

"in Zaydī Yemen, traditions remain which go back to a different transmitter of the text, Warsh."

it seems that Yamanī Zaydīs read Qālūn

The last two paragraphes are gibberish.

Monday, 27 July 2020

Kazan

Since 1802/3 (parts of) the Kur'an were printed in the Tartar centre of Tsarist Russia, Kazan.

Here the first and last page of a book from the Bavarian National Library;

Here the first and last page of a book from the Bavarian National Library;

the left side is page 58 of ǧuz 5 -- each ǧuz is paginated afresh

Like the 1787 Mollah Ismaʿīl ʿOsman St.Petersburg Muṣḥaf they were type printed.

I know of no studies on the orthography, the pauses, liturgical divisions and so

one.

and orthography: Where the original (black on white) is close to Ottoman, the modern one (black on yellow) has hamzat on alif, madda for lengthening, and alif alif for /ʾā/

Here the first and last page of a book from the Bavarian National Library;

Here the first and last page of a book from the Bavarian National Library;the left side is page 58 of ǧuz 5 -- each ǧuz is paginated afresh

Like the 1787 Mollah Ismaʿīl ʿOsman St.Petersburg Muṣḥaf they were type printed.

It clearly belongs to the Asian school, closest to Ottoman.

In the first 200

years there are small changes in calligraphy

and orthography: Where the original (black on white) is close to Ottoman, the modern one (black on yellow) has hamzat on alif, madda for lengthening, and alif alif for /ʾā/

Added later:

Walter Burnikel and Gerd-R. Puin published

„Gustav Flügels Vorworte, kommentiert. Ein Rückblick

auf die Geschichte des Korandrucks in Europa“ in

Markus Groß /Robert M. Kerr (Hg.):

Die Entstehung einer Weltreligion VI.

Vom umayyadischen Christentum zum abbasidischen Islam.

Berlin: Schiler & Mücke 2021, ISBN 978-3-89930-389-6

(INÂRAH Schriften zur frühen Islamgeschichte und zum Koran, Band 10), S. 64-129

with observations not only on Flügel and Redslob, but on Kazan (and Hamburg and Padua) too.

Since 2011 the rasm is very close to Gizeh 1924

The Tartar (both in Kazan and on the Crimea) most of the time have as title "Kalam Šarīf" (or al-Muṣḥaf aš-Ṣarīf) ‒ not "al-Qurʾān al-Karīm" (like the Arabs), nor "Q. maǧid" (like in Iran) nor "Q ḥakīm" (like in Hind).

Japanese Tartars being the exception:

here a page from a Japanese YaSīn edition:

Walter Burnikel and Gerd-R. Puin published

„Gustav Flügels Vorworte, kommentiert. Ein Rückblick

auf die Geschichte des Korandrucks in Europa“ in

Markus Groß /Robert M. Kerr (Hg.):

Die Entstehung einer Weltreligion VI.

Vom umayyadischen Christentum zum abbasidischen Islam.

Berlin: Schiler & Mücke 2021, ISBN 978-3-89930-389-6

(INÂRAH Schriften zur frühen Islamgeschichte und zum Koran, Band 10), S. 64-129

with observations not only on Flügel and Redslob, but on Kazan (and Hamburg and Padua) too.

Since 2011 the rasm is very close to Gizeh 1924

Sunday, 12 January 2020

Kein Standard Six, Before 1924

When you want to understand The French Revolution, you should not start with Storming the Bastille,

but with the economic, social and political situation in the decade before.

In order to understand the importance of the King Fuʾād Edition,

we will have a look on the technical side of book printing,

the science of "rasm and dabṭ",

the calligraphers writing maṣāḥif.

Let's start with debunking a statement made in the Muqaddima which was a leaflet put into the KFE.

In it it is stated that the government used to import foreign copies to be used in state schools, but that these often had to be distroyed because of mistakes. Around 1900 a substantial numbers had to be buried in the Nile.

I take it for a mystification. Imports came from Bairut, Damascus or Istanbul, all part of the Ottoman Empire, to which Egypt belonged upto November 1914.

I do not believe a story without exact year, numbers of copies confiscated and a list of mistakes

‒ and who paid how much in compensation to the owner of the books.

In the forty years before the KFE

several times the text of the qurʾān had been type printed in Būlāq:

both in Ottoman Style (eg. صِراط) with ḥarakāṭ

and bir-rasm al-ʿUṭmānī: as reported in Dānī's Muqniʿ, Ibn Naǧāḥ's Tabyīn or aš-Šāṭibī's ʿAqīla without ḥarakāt (صرط).

Local printers reproduced Ottoman lithographies (written by Hâfız Osman (1642–1698), by Haǧǧ Ḥāfiẓ ʿUṯmān Ḫalīfa QayišZāde an-Nūrī al-Burdurī d. 1894 or by Muṣṭafā Naẓīf Qadirġālī/ Kadirğali d. 1913 ‒ do not mix up with his fellow calligrapher Mehmed Naẓīf, who died in the same year) ‒ both with tafsīr and without.

That something is not the case,

is difficult to prove.

But I declare ‒ whatever others say: A 1833 Būlāq Muṣḥaf does not exist!

Before 1873, in the Ottoman Empire it was forbidden to print a muṣḥaf.

(For an illegal one see here.)

Starting 1874 many have been printed in Istanbul ‒ both by private and state presses.

Private printers (notably Muṣṭafā al-Bābī al-Ḥalabī) are said to have produced lithograph maṣāḥif in Cairo starting in the 1860s.

Because no exact years are given, and no name of the calligraphers,

and because in the 1880s more copies of Istanbul lithographs were printed in Cairo than local calligraphers,

I doubt that there were many ‒ anonymous ‒ Egyptian muṣḥaf writers before the 1880s.

The first Cairo lithograph I have seen is in the Azhar library (several copies there, one in Utah and at least one in Princeton)

In Michael W. Albin's article "Printing of the Qurʾān" in Brill's Encyclopedia of the Quran

it is mentioned as two different ones: one by the printer Muḥammad Abū Zaid, and one [directed, edited] by Muḥammad Raḍwān [sic].

It is the 1308/1890 copy directed/edited by Abū ʿĪd Riḍwān ibn Muḥammad ibn Sulaimān al-Muḫallalātī ( ١٢٥٠هـ-١٣١١هـ / 1834-1893), written by ʿAbdelḫāliq al-Ḥaqqī Ibn al-Ḫoǧa/Ibn al-Ḫawaǧa

Both in Istanbul

and Cairo

type set tafāṣīr with different spellings in the frame and at the margin were published

‒ in Būlāq the unvocalized rasm at the margin.

Both in large size for the use in Mosques,

gilded, with red as second colour for men of eminence, and small for craftsmen and housewives

lithographies written by the chief calligrapher of the Ottoman Marine were published.

Foundations, Tombs of Holy Men were offered expensive prints,

schools sets of cheap ones.

Three of his maṣāḥif are reproduced in other cities:

The one with 15 lines on 522 pages in Bairut, St. Petersburg, Tehran, in Cairo by ten different publishers ‒ as late as 1954 in the original Ottoman spelling by ʿAlī Yūsuf Sulaimān 1956

sometimes by the minstery of the Interior in the 1924 spelling,

the one with 15 lines on 604 pages in Tehran and Germany with red as additional colour,

in Nusantara in black and white (enriched with the {Indian} sign for /ū/,

the one with 17 lines on 486 pages in Damascus and by Turks in Germany.

Sometimes with tafsīr at the margins.

Sometimes with a different orthography.

Until today the version written by Muḥammad Saʿd al-Ḥaddād for aš-Šamarlī ‒ in style very similar to Muṣṭafā Naẓīf and line by line identical to the 522 page version is very popular ‒ a thousand times more popular than the Amiriyya prints, whose 855 page edition was never bought by normal Egyptians: it is no coincidence that the only copies of the original Giza prints survive in Orientalists libraries and studies.

In the 1960s aš-Šamarli had published the original by MNQ in the Q52 orthography (see on the left),

but from 1977 he sold al-Ḥaddād in different sizes, hardcover, plastic and soft;

Until today the version written by Muḥammad Saʿd al-Ḥaddād for aš-Šamarlī ‒ in style very similar to Muṣṭafā Naẓīf and line by line identical to the 522 page version is very popular ‒ a thousand times more popular than the Amiriyya prints, whose 855 page edition was never bought by normal Egyptians: it is no coincidence that the only copies of the original Giza prints survive in Orientalists libraries and studies.

In the 1960s aš-Šamarli had published the original by MNQ in the Q52 orthography (see on the left),

but from 1977 he sold al-Ḥaddād in different sizes, hardcover, plastic and soft;

on the right the original in Ottoman spelling;

Here a Bairūt edition in Q52 with explanations of words on the margin:

Here the Ottoman original

published by Muṣṭafā al-Bābī al-Ḥalābī before MNQ had died (1913)

Here the Ottoman original

published by Muṣṭafā al-Bābī al-Ḥalābī before MNQ had died (1913)

The 815 page muṣḥaf by Hafiz Osman (1642-98) was printed in Cairo with one of the bigger Tafsir around, in Syria it was till about 1960 the muṣḥaf

Here pages 2 + 3 from the Cairo print (without the commentary)

At least until islamist Qaṭar supplied islamist forces in Syria with arms and money thus starting a bitter "civil" war, in Aleppo "Ottoman" parts of the Qurʾān were printed:

and until 1990 in al-ʿIrāq two Ottoman maṣāḥif were printed by the state.

in the Turkish Republic only expensive facsimiles reproduce old manuscripts,

"reprints" for believers are heavily edited.

In 1370/1951 the ʿIrāqi Dīwān al-ʾAuqāf had it printed under the supervision of Naǧmaddīn al-Wāʾiz with Kufi numbers after each verse and sura title boxes written by Hāšim Muḥammad al-Ḫaṭṭāt al-Baġdādī,

1386/1966 for the ʿirāqī state by Lohse in Frankfurt/Main,

1398/1978 for the suʿūdī government in West Germany,

1400/1979 in Qaṭar, 1401/1981 for Ṣaddām.

In 1236 Muḥammad Amīn ar-Rušdī had written the original muṣḥāf. In 1278 ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz's mother offered it to the tomb of Junaid in Baghdād. Today it is kept in the library of the tomb of Abu Ḥanīfa.

Whereas in the manuscript ‒ as I guess ‒ waṣl-sign were only on alifs before sun-letters, in the ʿIrāqi print most initial alifs have one, which leads to the annomaly that sometimes an alif has both "waṣl" underneath and a waṣl-sign above.

After every tenth verse a yāʾ (in the abjad system: ten) hovers before the number (see above); what was helpful in the original manuscript that had only end-of-verse-markers, is kind of ridiculous in the printed edition.

Of interest as well: "bi-yāʾ wāhida" under riyyīn in 5:111, which in another Ottoman muṣḥaf is written yāʾ + šadda + turned kasra + yāʾ and in the mordern Turkish ones with one yāʾ and in Q24 with a normal yāʾ plus a high small one. Brockett studied in Edinburgh an Ottoman Manuscript from 1800, in which under 41:47 bi-ʾaidin bi-yāʾain is written. How-to-write-notes were common (in the same Ms. in 43:3 under a hamza-letter "bi-ġair alif" is written.

The Dīwān al-auqāf published ‒ with similar front and back matter ‒ reprints by Ḥafiz ʿUṯmān and Ḥasan Riḍā.

on the right the cover of the M.A. ar-Rušdī edition, in the middle Ḥasan Riḍā, on the left the editor. ‒ After the US-intervention there are two authorities: Dīwān al-waqf as-sunnī and ... aš-šiʿī, both published maṣāḥif on 604 pages: the Sunni took the text from KFC (UT1, cf Kein Standard), the Ši'i had the ʿirāqī Calligrapher, Hādī ad-Darāǧī, write it.

In anearlier post (and above) I retold the history of the manuscript and its prints.

Except for the backmatter and the division into aḥzāb they are all the same: al-Wāʾiz's edition Recently I learned that in 1415/1994 an Iranian reprint was made ‒ not based on the manuscript but on the ʿirāqī version. While the ihmal-sign were deleted already in 1370/1951, forty years later other "confusing" stuff had to go:

‒ high yāʾ barī for every tenth verse,

‒ the differentiation between leading alif followed by a ḥarf sākin and others ‒ now ALL alifs-waṣl have a waṣl-sign (head of صـ)

‒ signs for pauses or vowels are placed nearer to "their" base letter

‒ sometimes the space between words is enlarged, a swash nūn replaced by a normal one

‒ a normal ḍamma-sign was replaced by a turned one, where it is pronouinced ū (due to rules of prosody)

‒ Mūsā gets a long-fatḥa,

Is there someone who has images of the manuscript?

on the right the first "normal" page of Muḥ. ʾAmīn ar-Rušdī's muṣḥaf, on the left: Ḥasan Riḍā:

Remarkable below:

Remarkable below:

‒ in lignes 3,5,6,7,9: the boundary between words is between alifs

‒ in lign 2: before (10) a small high yāʾ, which in the manucrpt was needed to signal: 10

‒ some Ihmal-signs below letter signalling: without dot

In order to understand the importance of the King Fuʾād Edition,

we will have a look on the technical side of book printing,

the science of "rasm and dabṭ",

the calligraphers writing maṣāḥif.

Let's start with debunking a statement made in the Muqaddima which was a leaflet put into the KFE.

In it it is stated that the government used to import foreign copies to be used in state schools, but that these often had to be distroyed because of mistakes. Around 1900 a substantial numbers had to be buried in the Nile.

I take it for a mystification. Imports came from Bairut, Damascus or Istanbul, all part of the Ottoman Empire, to which Egypt belonged upto November 1914.

I do not believe a story without exact year, numbers of copies confiscated and a list of mistakes

‒ and who paid how much in compensation to the owner of the books.

In the forty years before the KFE

several times the text of the qurʾān had been type printed in Būlāq:

both in Ottoman Style (eg. صِراط) with ḥarakāṭ

and bir-rasm al-ʿUṭmānī: as reported in Dānī's Muqniʿ, Ibn Naǧāḥ's Tabyīn or aš-Šāṭibī's ʿAqīla without ḥarakāt (صرط).

Local printers reproduced Ottoman lithographies (written by Hâfız Osman (1642–1698), by Haǧǧ Ḥāfiẓ ʿUṯmān Ḫalīfa QayišZāde an-Nūrī al-Burdurī d. 1894 or by Muṣṭafā Naẓīf Qadirġālī/ Kadirğali d. 1913 ‒ do not mix up with his fellow calligrapher Mehmed Naẓīf, who died in the same year) ‒ both with tafsīr and without.

That something is not the case,

is difficult to prove.

But I declare ‒ whatever others say: A 1833 Būlāq Muṣḥaf does not exist!

Before 1873, in the Ottoman Empire it was forbidden to print a muṣḥaf.

(For an illegal one see here.)

Starting 1874 many have been printed in Istanbul ‒ both by private and state presses.

Private printers (notably Muṣṭafā al-Bābī al-Ḥalabī) are said to have produced lithograph maṣāḥif in Cairo starting in the 1860s.

Because no exact years are given, and no name of the calligraphers,

and because in the 1880s more copies of Istanbul lithographs were printed in Cairo than local calligraphers,

I doubt that there were many ‒ anonymous ‒ Egyptian muṣḥaf writers before the 1880s.

The first Cairo lithograph I have seen is in the Azhar library (several copies there, one in Utah and at least one in Princeton)

In Michael W. Albin's article "Printing of the Qurʾān" in Brill's Encyclopedia of the Quran

it is mentioned as two different ones: one by the printer Muḥammad Abū Zaid, and one [directed, edited] by Muḥammad Raḍwān [sic].

It is the 1308/1890 copy directed/edited by Abū ʿĪd Riḍwān ibn Muḥammad ibn Sulaimān al-Muḫallalātī ( ١٢٥٠هـ-١٣١١هـ / 1834-1893), written by ʿAbdelḫāliq al-Ḥaqqī Ibn al-Ḫoǧa/Ibn al-Ḫawaǧa

Both in Istanbul

and Cairo

type set tafāṣīr with different spellings in the frame and at the margin were published

‒ in Būlāq the unvocalized rasm at the margin.

Both in large size for the use in Mosques,

gilded, with red as second colour for men of eminence, and small for craftsmen and housewives

lithographies written by the chief calligrapher of the Ottoman Marine were published.

Foundations, Tombs of Holy Men were offered expensive prints,

schools sets of cheap ones.

Three of his maṣāḥif are reproduced in other cities:

The one with 15 lines on 522 pages in Bairut, St. Petersburg, Tehran, in Cairo by ten different publishers ‒ as late as 1954 in the original Ottoman spelling by ʿAlī Yūsuf Sulaimān 1956

sometimes by the minstery of the Interior in the 1924 spelling,

the one with 15 lines on 604 pages in Tehran and Germany with red as additional colour,

in Nusantara in black and white (enriched with the {Indian} sign for /ū/,

the one with 17 lines on 486 pages in Damascus and by Turks in Germany.

Sometimes with tafsīr at the margins.

Sometimes with a different orthography.

Until today the version written by Muḥammad Saʿd al-Ḥaddād for aš-Šamarlī ‒ in style very similar to Muṣṭafā Naẓīf and line by line identical to the 522 page version is very popular ‒ a thousand times more popular than the Amiriyya prints, whose 855 page edition was never bought by normal Egyptians: it is no coincidence that the only copies of the original Giza prints survive in Orientalists libraries and studies.

In the 1960s aš-Šamarli had published the original by MNQ in the Q52 orthography (see on the left),

but from 1977 he sold al-Ḥaddād in different sizes, hardcover, plastic and soft;

Until today the version written by Muḥammad Saʿd al-Ḥaddād for aš-Šamarlī ‒ in style very similar to Muṣṭafā Naẓīf and line by line identical to the 522 page version is very popular ‒ a thousand times more popular than the Amiriyya prints, whose 855 page edition was never bought by normal Egyptians: it is no coincidence that the only copies of the original Giza prints survive in Orientalists libraries and studies.

In the 1960s aš-Šamarli had published the original by MNQ in the Q52 orthography (see on the left),

but from 1977 he sold al-Ḥaddād in different sizes, hardcover, plastic and soft;on the right the original in Ottoman spelling;

Here a Bairūt edition in Q52 with explanations of words on the margin:

Here the Ottoman original

published by Muṣṭafā al-Bābī al-Ḥalābī before MNQ had died (1913)

Here the Ottoman original

published by Muṣṭafā al-Bābī al-Ḥalābī before MNQ had died (1913)

The 815 page muṣḥaf by Hafiz Osman (1642-98) was printed in Cairo with one of the bigger Tafsir around, in Syria it was till about 1960 the muṣḥaf

Here pages 2 + 3 from the Cairo print (without the commentary)

At least until islamist Qaṭar supplied islamist forces in Syria with arms and money thus starting a bitter "civil" war, in Aleppo "Ottoman" parts of the Qurʾān were printed:

and until 1990 in al-ʿIrāq two Ottoman maṣāḥif were printed by the state.

in the Turkish Republic only expensive facsimiles reproduce old manuscripts,

"reprints" for believers are heavily edited.

In 1370/1951 the ʿIrāqi Dīwān al-ʾAuqāf had it printed under the supervision of Naǧmaddīn al-Wāʾiz with Kufi numbers after each verse and sura title boxes written by Hāšim Muḥammad al-Ḫaṭṭāt al-Baġdādī,

1386/1966 for the ʿirāqī state by Lohse in Frankfurt/Main,

1398/1978 for the suʿūdī government in West Germany,

1400/1979 in Qaṭar, 1401/1981 for Ṣaddām.

In 1236 Muḥammad Amīn ar-Rušdī had written the original muṣḥāf. In 1278 ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz's mother offered it to the tomb of Junaid in Baghdād. Today it is kept in the library of the tomb of Abu Ḥanīfa.

Whereas in the manuscript ‒ as I guess ‒ waṣl-sign were only on alifs before sun-letters, in the ʿIrāqi print most initial alifs have one, which leads to the annomaly that sometimes an alif has both "waṣl" underneath and a waṣl-sign above.

After every tenth verse a yāʾ (in the abjad system: ten) hovers before the number (see above); what was helpful in the original manuscript that had only end-of-verse-markers, is kind of ridiculous in the printed edition.

Of interest as well: "bi-yāʾ wāhida" under riyyīn in 5:111, which in another Ottoman muṣḥaf is written yāʾ + šadda + turned kasra + yāʾ and in the mordern Turkish ones with one yāʾ and in Q24 with a normal yāʾ plus a high small one. Brockett studied in Edinburgh an Ottoman Manuscript from 1800, in which under 41:47 bi-ʾaidin bi-yāʾain is written. How-to-write-notes were common (in the same Ms. in 43:3 under a hamza-letter "bi-ġair alif" is written.

The Dīwān al-auqāf published ‒ with similar front and back matter ‒ reprints by Ḥafiz ʿUṯmān and Ḥasan Riḍā.

on the right the cover of the M.A. ar-Rušdī edition, in the middle Ḥasan Riḍā, on the left the editor. ‒ After the US-intervention there are two authorities: Dīwān al-waqf as-sunnī and ... aš-šiʿī, both published maṣāḥif on 604 pages: the Sunni took the text from KFC (UT1, cf Kein Standard), the Ši'i had the ʿirāqī Calligrapher, Hādī ad-Darāǧī, write it.

In anearlier post (and above) I retold the history of the manuscript and its prints.

Except for the backmatter and the division into aḥzāb they are all the same: al-Wāʾiz's edition Recently I learned that in 1415/1994 an Iranian reprint was made ‒ not based on the manuscript but on the ʿirāqī version. While the ihmal-sign were deleted already in 1370/1951, forty years later other "confusing" stuff had to go:

‒ high yāʾ barī for every tenth verse,

‒ the differentiation between leading alif followed by a ḥarf sākin and others ‒ now ALL alifs-waṣl have a waṣl-sign (head of صـ)

‒ signs for pauses or vowels are placed nearer to "their" base letter

‒ sometimes the space between words is enlarged, a swash nūn replaced by a normal one

‒ a normal ḍamma-sign was replaced by a turned one, where it is pronouinced ū (due to rules of prosody)

‒ Mūsā gets a long-fatḥa,

Is there someone who has images of the manuscript?

on the right the first "normal" page of Muḥ. ʾAmīn ar-Rušdī's muṣḥaf, on the left: Ḥasan Riḍā:

‒ in lignes 3,5,6,7,9: the boundary between words is between alifs

‒ in lign 2: before (10) a small high yāʾ, which in the manucrpt was needed to signal: 10

‒ some Ihmal-signs below letter signalling: without dot

‒ genau wie bei Rušdi gibt es vor ḥurūf sākina, also vor einem Buchstaben mit sukûn oder vor weg-assimiliertem lām, also vor Buchstaben mit šadda; das waṣl-Zeichen ist überflüssig; heute (im Standard der türkischen Republik) wird es weggelassen.) ‒ Das /fī/ in Zeile drei besteht nur aus Fehlern: Was machen die Punkte beim End-yāʾ? cf. /fī qulubihim/ two lines above has no dots, althought there it is /ī/

Was macht das Langvokalzeichen vor Doppelkonsonanz? Und wieso steht das (Lang-)kasra über dem yāʾ statt darunter? ‒ Ist aber üblich so.

‒ in den Zeile 1,3 und 7 gibt es ǧazm-Zeichen über ḥurûf al-madd.

‒‒‒ dass man den Bezug zwischen ǧazm-Zeichen über dem ḥarf al-madd der ersten Zeile besser sieht, habe ich die Zeichen so platziert, wie sie nach "modernem" Verständnis sitzen müssen.

hier ist ein Blatt los, man erkennt trotzdem den Anfang von Baqara

hier ist ein Blatt los, man erkennt trotzdem den Anfang von Baqara Hier sieht man, dass MNQ ‒ vielleicht mit Ausnahme der ersten und letzten Seiten ‒ nur ein paar Mal alles geschrieben hat, die Verleger daraus viele unterschiedliche Fassungen zauberten.

Hier sieht man, dass MNQ ‒ vielleicht mit Ausnahme der ersten und letzten Seiten ‒ nur ein paar Mal alles geschrieben hat, die Verleger daraus viele unterschiedliche Fassungen zauberten.

Manchmal schöner aus einer Ausgabe mit schwarzen und roten Madd-Zeichen

aus einer Ausgabe mit schwarzen und roten Madd-Zeichen

Eine Ausgabe auf 485 Seiten ‒ die letzte Sure steht auf S. 486, weil die erste Sure auf Seite 2 steht ‒ wurde in Damaskus auf Glanzpapier "edel" und in Deutz in wattiertem Plastikumschlag preiswert veröffentlicht, nur die deutschen Türken geben den Kalligraphen an.

Eine Ausgabe auf 485 Seiten ‒ die letzte Sure steht auf S. 486, weil die erste Sure auf Seite 2 steht ‒ wurde in Damaskus auf Glanzpapier "edel" und in Deutz in wattiertem Plastikumschlag preiswert veröffentlicht, nur die deutschen Türken geben den Kalligraphen an.

aus einer Ausgabe mit schwarzen und roten Madd-Zeichen

aus einer Ausgabe mit schwarzen und roten Madd-Zeichen

Eine Ausgabe auf 485 Seiten ‒ die letzte Sure steht auf S. 486, weil die erste Sure auf Seite 2 steht ‒ wurde in Damaskus auf Glanzpapier "edel" und in Deutz in wattiertem Plastikumschlag preiswert veröffentlicht, nur die deutschen Türken geben den Kalligraphen an.

Eine Ausgabe auf 485 Seiten ‒ die letzte Sure steht auf S. 486, weil die erste Sure auf Seite 2 steht ‒ wurde in Damaskus auf Glanzpapier "edel" und in Deutz in wattiertem Plastikumschlag preiswert veröffentlicht, nur die deutschen Türken geben den Kalligraphen an.

> ... es sei denn du fast ihn selbst "verbessert"!

Haǧǧ Ḥāfiẓ ʿUṯmān Ḫalīfa QayišZāde an-Nūrū al-Burdurī (Hac Hattat Kayışzade Hafis Osman Nuri Efendi Burdurlu) schrieb 106 1/2 maṣāḥif. Den auf 815 Seten (ohne das Abschlussgebet, den Index und das Kolophon) ist sehr oft und sehr lange in Syrien (und auch in Ägypten allein oder mit tafsīr) nachgedruckt worden, einen der 604seitigen gibt es immer noch in der Türkei.

Links ein Damaszener Druck vor 1950 mit vielen Zeichen, die später getilgt wurden:

kleines hā' und yā' für Fünf und Zehn (15,20, 25,30 ...)

zwei Kleinbuchstaben (immer eines davon bā') über baṣrische Verszählung

kleine punktlose Buchstaben unter oder über einem punktlosen Buchstaben, um zu betonen, dass da kein Punkt fehlt (oder auch لا, was wie ein V oder VogelFlügel aussieht ‒ in manchen Manuskripten bekommen dāl und rāʾ einen Punkt darunter, um zu sagen nicht-zāʾ, nicht-ḏāl).

In der Mittel (auf blassgrünem Grund) habe ich zwei Stellen hervorgehoben:

bei der ersten haben die modernen türkischen Bearbeiter (siehe rechts /gelblich) die zwei Wörter von anderen Stellen im muṣḥaf hierhinkopiert, damit es klar und deutlich von Rechts nach links geht, damit jedes Vokalzeichen "richtig" platziert ist.

bei der zweiten Stelle haben sich die Herausgeber an dem 815er muṣḥaf bedient, um den rasm zu "korrigieren":

beginning of verse 94 of Ṭaha 94:

Modern editors often improve old manuscripts.

In Ottoman mss. there are waṣl-signs on alifs ONLY before an unvowelled letter ‒ most of the time before the lām of the article before a sun-letter.

Modern Iranian reprint editors put waṣl-signs wherever one puts them according to modern rules.

Turkish editors follow the Indian practise: no waṣl-signs (vowel-sign includes hamza, no sign IS waṣl)

In the mss. wau-hamza stands sometimes for wau plus hamza. When the wau is ONLY hamza-carrier, sometimes ‒ when a misreading is deemed likely ‒ one finds qṣr under the wau.

Now in Turkey, always when it is not ḥarf al-madd plus hamza, one finds the reading help ‒ and madd underneath when it is both hamza and /ū/.

Modernity demands clarity: either always (Iran) or never (Turkey).

Ḥasan Riḍā and Muḥ ar-Rušdī (second and forth line of ʿiraqī prints with verse numbers and title boxes) have no "qiṣr" seeing no danger that one could read it /ūʾ/.

1a) Diyanet gets ridd of all "confusing" signs. In the first line (of a "14th" print of a Hafiz Osman muṣḥaf, 1987) there is still a waṣl-sign (more clearly in the third line ‒ an Hafiz Osman original ‒ now it is gone.

I guess that the Diyanet editor did not realized that the (now missing) alif-waṣl reminds of Ibn.

2.) Diyanet moves slightly from the Ottoman practise to the Suʿudi standard (Q52).

Here they follow ad-Dānī: three (real) word as one. In his 1309er (hiǧri) muṣḥaf (last line before the computer set one) Hafiz Osman had written "oh, mother's son" in one word.

Diyanet has established a standard of 604/5 pages, often moves word or letters to make old manuscripts according to the new set.

Haǧǧ Ḥāfiẓ ʿUṯmān Ḫalīfa QayišZāde an-Nūrū al-Burdurī (Hac Hattat Kayışzade Hafis Osman Nuri Efendi Burdurlu) schrieb 106 1/2 maṣāḥif. Den auf 815 Seten (ohne das Abschlussgebet, den Index und das Kolophon) ist sehr oft und sehr lange in Syrien (und auch in Ägypten allein oder mit tafsīr) nachgedruckt worden, einen der 604seitigen gibt es immer noch in der Türkei.

Links ein Damaszener Druck vor 1950 mit vielen Zeichen, die später getilgt wurden:

kleines hā' und yā' für Fünf und Zehn (15,20, 25,30 ...)

zwei Kleinbuchstaben (immer eines davon bā') über baṣrische Verszählung

kleine punktlose Buchstaben unter oder über einem punktlosen Buchstaben, um zu betonen, dass da kein Punkt fehlt (oder auch لا, was wie ein V oder VogelFlügel aussieht ‒ in manchen Manuskripten bekommen dāl und rāʾ einen Punkt darunter, um zu sagen nicht-zāʾ, nicht-ḏāl).

In der Mittel (auf blassgrünem Grund) habe ich zwei Stellen hervorgehoben:

bei der ersten haben die modernen türkischen Bearbeiter (siehe rechts /gelblich) die zwei Wörter von anderen Stellen im muṣḥaf hierhinkopiert, damit es klar und deutlich von Rechts nach links geht, damit jedes Vokalzeichen "richtig" platziert ist.

bei der zweiten Stelle haben sich die Herausgeber an dem 815er muṣḥaf bedient, um den rasm zu "korrigieren":

beginning of verse 94 of Ṭaha 94:

Modern editors often improve old manuscripts.

In Ottoman mss. there are waṣl-signs on alifs ONLY before an unvowelled letter ‒ most of the time before the lām of the article before a sun-letter.

Modern Iranian reprint editors put waṣl-signs wherever one puts them according to modern rules.

Turkish editors follow the Indian practise: no waṣl-signs (vowel-sign includes hamza, no sign IS waṣl)

In the mss. wau-hamza stands sometimes for wau plus hamza. When the wau is ONLY hamza-carrier, sometimes ‒ when a misreading is deemed likely ‒ one finds qṣr under the wau.

Now in Turkey, always when it is not ḥarf al-madd plus hamza, one finds the reading help ‒ and madd underneath when it is both hamza and /ū/.

Modernity demands clarity: either always (Iran) or never (Turkey).

Ḥasan Riḍā and Muḥ ar-Rušdī (second and forth line of ʿiraqī prints with verse numbers and title boxes) have no "qiṣr" seeing no danger that one could read it /ūʾ/.

1a) Diyanet gets ridd of all "confusing" signs. In the first line (of a "14th" print of a Hafiz Osman muṣḥaf, 1987) there is still a waṣl-sign (more clearly in the third line ‒ an Hafiz Osman original ‒ now it is gone.

I guess that the Diyanet editor did not realized that the (now missing) alif-waṣl reminds of Ibn.

2.) Diyanet moves slightly from the Ottoman practise to the Suʿudi standard (Q52).

Here they follow ad-Dānī: three (real) word as one. In his 1309er (hiǧri) muṣḥaf (last line before the computer set one) Hafiz Osman had written "oh, mother's son" in one word.

Diyanet has established a standard of 604/5 pages, often moves word or letters to make old manuscripts according to the new set.

In the forty years before the KFE several times the text of the qurʾān had been type printed in Būlāq:

both in Ottoman Style (eg. صِراط) with ḥarakāṭ

and bir-rasm al-ʿUṭmānī: as reported in Dānī's Muqniʿ, Ibn Naǧāḥ's Tabyīn or aš-Šāṭibī's ʿAqīla without ḥarakāt (صرط).

Local printers reproduced Ottoman lithographies (written by Hâfız Osman (1642–1698), by Haǧǧ Ḥāfiẓ ʿUṯmān Ḫalīfa QayišZāde an-Nūrī al-Burdurī d. 1894 or by Muṣṭafā Naẓīf Qadirġālī/ Kadirğali d. 1913 ‒ do not mix up with his fellow calligrapher Mehmed Naẓīf, who died in the same year) both with tafsīr and without.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Nairīzī

Mirza Aḥmad an-Nairīzī (ca. 1650–1747) is the last of the classical Iranian calligraher s. Informations are hard to find, because often und...

-

There are several types of madd sign in the Qurʾān, in South Asian masāhif: madd al-muttasil for a longer lengthening of the vowel used...

-

40 years ago Adrian Alan Brockett submitted his Ph.D. to the University of St.Andrews: Studies in Two Transmissions of the Qurʾān . Now...

-

Although it is often written that the King Fuʾād Edition fixed a somehow unclear text, and established the reading of Ḥafṣ according to ʿĀ...