Friday, 19 July 2024

What makes a certain muṣḥaf?

A muṣḥaf is not just the words of the qurʾān.

It's not just the words in a certain spelling (rasm + diacritical points + ḍabṭ)

not just these words plus pronounciation signs plus pause signs.

In this post (and this blog generally) I ignore the qiraʾāt.

In this post I further ignore the features of a printed mushaf

(lines per pages, number of pages, catch words, marginal notes).

But there is an element that some orientalists ignore:

the titel box or rather the information therein.

The makers of Coran 12-21 claim to give "The Cairo Edition (1924)"

but their list of suras and the suras themselves have no number,

no information about the number of ayas,

no information on the order of revelation,

informations the KFE (1924) had:

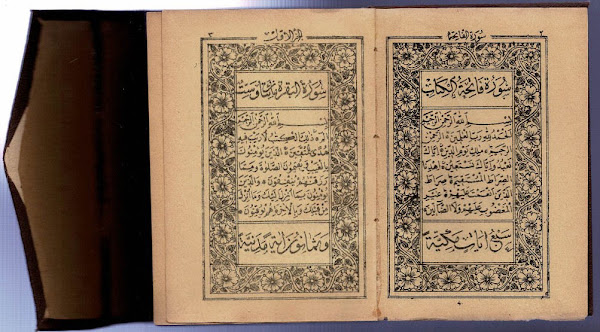

Here the titelbox of 1952 (without information about the order of revelation:

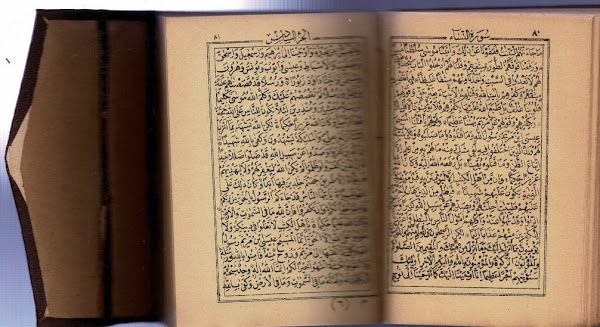

Here the titelbox of UT0 (i.e. the original ʿUṯmān Ṭaha copy as printed in Damascus:

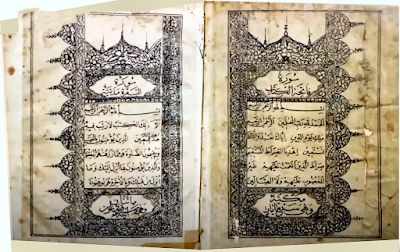

And here what the Suʿudis (KFC) made out of it (I call it UT1):

unchanged in UT2 (the text written in Madina):

Although claiming to show "The Cairo Edition (1924)",

what Coran 12-21 really shows is the Suʿudī version: without numbers (1-114), without information on the number of ayas,

without information about the order of revelation.

On top of this, Coran 12-21 has the wrong number of ayas (counting the basmala as verse 1),

and has no small letters to indicate pronounciation,

21:89 فَاسْتَجَبْنَا لَهُ وَنَجَّيْنَاهُ مِنَ الْغَمِّ وَكَذَلِكَ نُنجِي الْمُؤْمِنِينَ

21:88 نُجِۨی

In the two lines above ‒ as in the examples below ‒

always first the wrong Coran 12-21 text

and in the next line the correct Giza 1924 text (from Corpus Coranicum)

2:246 وَاللَّهُ يَقْبِضُ وَيَبْسُطُ وَإِلَيْهِ تُرْجَعُونَ

2:245 وَيَبۡصُۜطُ

7:70 فِي الْخَلْقِ بَسْطَةً فَاذْكُرُوا آلَاءَ اللَّهِ لَعَلَّكُمْ تُفْلِحُونَ

7:69 بَصۜۡطَة

88:23 لَّسْتَ عَلَيْهِم بِمُصَيْطِرٍ

88:22 بِمُصَۣيۡطِرٍ

77:21 عَلِمَ أَن لَّن

77:20 عَلِمَ أَلَّن

nor pause signs:

2:6 أُولَئِكَ عَلَى هُدًى مِّن رَّبِّهِمْ وَأُولَئِكَ هُمُ الْمُفْلِحُونَ

2:5 أُو۟لَٰٓئِكَ عَلَىٰ هُدًۭى مِّن رَّبِّهِمۡۖ

وَأُو۟لَٰٓئِكَ هُمُ ٱلۡمُفۡلِحُونَ

And while "the Cairo Edition (1924)" has three different tanwīn for each of the three vowels,

Coran 12-21 has just one, e.g.

105:6 فَجَعَلَهُمْ كَعَصْفٍ مَّأْكُولٍ

whereas Giza 1924 has a sequential kastatain

2:6 أُولَئِكَ عَلَى هُدًى مِّن رَّبِّهِمْ

It took me three days to understand:

The makers of the web site have no idea what "Cairo 1924" is,

they take a random Arab Qurʾānic text (from tanzil.net) and call it "Cairo Edition, 1924" although it is not called that in their source.

They are only interested in translations.

Fine. But:please don't call a text which does not even have waṣl-sign "Cairo 1924" -- please!

Monday, 15 July 2024

Hassan Chahdi on the King Fu'ad Edition

There is a text in the web

Chahdi is an expert on The Qur’an, its Transmission and Textual Variants: Confronting Early Manuscripts and Written Traditions,

Le muṣḥaf dans les débuts de l'islam.

Le paradoxe de la transmission du Coran : entre riwāya et qiyās ?

Entre qirā’āt et variantes du rasm

He gives as his main interests:

Élaboration des textes fondamentaux de l'islam : contexte et processus de canonisation.

Manuscrits coraniques : graphie (rasm) et variantes de lectures (qirā'āt)

Écoles théologiques et systèmes juridiques des débuts de l'islam : fondements et doctrines

Littérature et poésie arabe (pré-islamique, islamique et moderne) : analyse linguistique, stylistique et métrique,

Histoire des pouvoirs et des savoirs.

As the history of printed maṣāḥif is not among his interests,

the third of his article that is devoted to it, is just rubbish

and the two good thirds of the article have hardly to do with the KFE.

He starts like this:

-- . --

١٣٤٣ هجرّية

سـنة

As indicated in the bibliography, it is called "Muṣḥaf al-misāḥa wal amīriyya" after the institution that printed it (al-misāḥa = l'office national de l'information géographique = Egyptian General Survey Authority = Grundbuchamt = الهيئة المصرية العامة للمساحة) and the institution that published it (al-amīriyya). After the stamp, it is called "Egyptian Government Edition" or "der amtliche ägyptische Koran" (G.Bergsträßer), or "the 12 liner/مصحف 12 سطر" or "the 1925 King Fuʾād Edition" because there are slightly different editions in 1926,1927,1929 and an edition with almost 1000 changes (mostly just different pause signs) from 1952 ‒ all are called "Muṣḥaf al-Amīriyya", the first (al-Muṣḥaf al-misāḥa wa'l amīriyya) was made by al-Ḥusainī al-Ḥaddād al-Mālikī (d. 22.1. 1939) and the 1952 one by ʿAlī Muḥammad aḍ-Ḍabbāʿ(1304/1886-1380/1960) ‒ only the large editions (27 x 20 cm) were printed by al-misāḥa in Giza (already in 1925 there was a smaller offset printing press in Bulāq ‒ the one in Giza could print large maps). And while the early editions have nothing to do with al-Azhar, in 1952 ʿulemāʾ were involved. BTW, 1952, but before the revolution. 12 line is special, most others in Egypt (Muṣṭafā Naẓīf, aš-Šamarli/Muḥammad Saʿd Ibrāhīm al-Ḥaddād (1919-2011), Haǧǧ Ḥāfiẓ, ʿUṯmān Ḫalīfa QayišZāde an-Nūrī al-Burdurī d. 1894,ʿUṯmān Ṭaha) have 15 lines on a text page, the South African edition on 848 pages has 13 lines; just Pakistan where everything from 9 to 18 lines is common (even 6liner and 21liner exist), produces copies with 12 lines of Arabic text (both with and without interlinear translations).

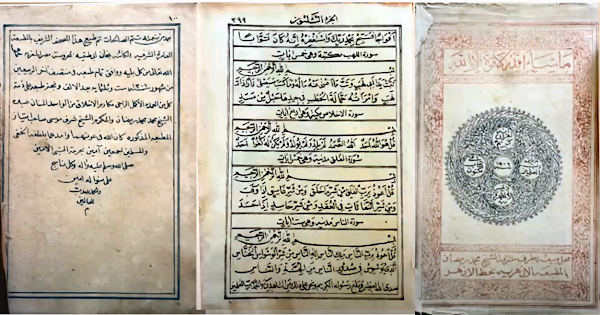

All written by they same calligrapher who wrote the tremendously important 1308/1890 edition, ʿAbd al-Ḫālliq Ḥaqqī Ibn al-Ḫawaǧa, by the editor Šaiḫ Aḥmad bin ʿAlī al-Melīǧī al-Kutbī, who had a press near al-Azhar until 1919. From a copy held in a Catholic Theological Seminar in Frankurt/Main, printed 1315/1898 on 468 pages with 17 lines:

Innahu li-Qurʾān karīm fī kitāb maknūn lā yamassahu illā al-muṭahhirūn tanzīl min ...

Miṣr : al-Maṭbaʻah al-ʻĀmirīyah, 1318 [1900]

364 pp. 19 lines ; 20 cm.

all from before "the first print in the Arab world": « le manuscrit coranique intégralement écrit de la main du savant ... al-Muhallalātī » ‒ was a book printed in 1890 in al-Qāhira (see above and below) La commission mandatée par le roi Fouad est composée d’éminents savants ‒ there was no commission, they never met, they dit not discuss the text of the edition The chief reader قارئ of Egypt Muḥammad ʿAlī al-Ḥusainī al-Ḥaddād was the only Islamic scholar in the "commission"; the other three are from the Minstry of Education or the Pedagogical College next door: Hanafî Nâsif ‒ really Ḥifnī Bey Nāṣif (on his visting card: Nassef) d.1919 ʿAnānī ‒ Muṣṭafā (al-)ʿInānī (d.1362/1943) Aḥmad al-Askandarānī ‒ Aḥmad ibn ʿAlī ibn ʿUmar al-Iskandarī (1292‒1357/1875‒1938) ‒ Ḥifnī Bey Nāṣif died before any work on the edition started. I assume it was mainly his idea; the date given for the signatures is just before his death thus honouring the initiator of the edition. among the countries that have editions of their own Pakistan is mentioned, ‒ but not India, although there were important edition before and after 1947 (in Calcutta, Hooghli, Kanpure, Lucknow, Bombay, Delhi ...) Mais seule l’édition saoudienne de Médine fait vraiment concurrence à celle du Caire ‒ I'd say the opposite: first the KFE was hardly bought by Arabs, but the edition that I call "Uṯmān Ṭaha 1 / UT1" made in Medina is the one that enshrines the text of the KFE albeit the one of the 1952 edition with minor differences le ductus consonantique correspond , schématiquement , au squelette orthographique ‒ orthographique skeleton is fine, but as the Arabic script has letters (not vowels and consonants) the first expression makes no sense La commission pour l’édition du Caire se fonde sur le système de lecture de Hafs Ibn Sulaymân, ou plus précisément sur le manuscrit coranique intégralement écrit de la main du savant égyptien Radwân b. Muhammad al-Muhallalātī ‒ Abū ʿĪd Riḍwān ibn Muḥammad ibn Sulaimān al-Muḫallalātī ( ١٢٥٠-١٣١١/1834-1893) was the editor of the important edition, but the scribe was ʿAbdelḫāliq al-Ḥaqqī Ibn al-Ḫoǧa/Ibn al-Ḫawaǧa; al-Muḫallalātī's edition is important, he broke with the Ottoman orthography, instead followed in some respects the Indian system ‒ and is closer to ad-Dānī's rasm BUT al-Ḥusainī al-Ḥaddād did not follow his orthography, but more the Moroccon (Andalusian, Western) orthography ‒ and is closer to Abu Sulaimān Ibn Naǧāḥ's rasm. And there is something that could be misunderstood: on retrouve [dans les codices anciens] notamment des variantes de lecture extra-canoniques, antérieures à la période de standardisation du corpus coranique. ‒ Marijn van Putten and others have shown that ALL manuscripts follow the ʿUṯmānic rasm (diacritica and voweling non conforming to any of the canonical readings do not amount to differences in the rasm) with the exception of the erased text of the Sanaʾa Palimpsest. If it were « antérieures à la période de standardisation» des qira'āt, riwayāt et ṭuruq, it would have been clearer. ‒ ‒ ‒ ‒ ‒ ‒

The Cairo edition was published in 1924 by the printing press of Bulaq... This edition is also called the “Royal edition” (al-malikiyya or al-amīriyya)Yes, it might have left the printing press in 1342/1924, but the press of the Survey of Egypt, which lies not in al-Qāhira, not in the City of Cairo, not even in the Cairo Governorate, but on the left side of the Nile: in Giza. yes, it was published by the Goverment Printing Press in Bulāq, the Amīriyya, but in 1343/1925: type set in Bulāq, printed in Giza, bound, stamped and published in Bulāq. طبعة الحكومية المصرّية

-- . --

١٣٤٣ هجرّية

سـنة

As indicated in the bibliography, it is called "Muṣḥaf al-misāḥa wal amīriyya" after the institution that printed it (al-misāḥa = l'office national de l'information géographique = Egyptian General Survey Authority = Grundbuchamt = الهيئة المصرية العامة للمساحة) and the institution that published it (al-amīriyya). After the stamp, it is called "Egyptian Government Edition" or "der amtliche ägyptische Koran" (G.Bergsträßer), or "the 12 liner/مصحف 12 سطر" or "the 1925 King Fuʾād Edition" because there are slightly different editions in 1926,1927,1929 and an edition with almost 1000 changes (mostly just different pause signs) from 1952 ‒ all are called "Muṣḥaf al-Amīriyya", the first (al-Muṣḥaf al-misāḥa wa'l amīriyya) was made by al-Ḥusainī al-Ḥaddād al-Mālikī (d. 22.1. 1939) and the 1952 one by ʿAlī Muḥammad aḍ-Ḍabbāʿ(1304/1886-1380/1960) ‒ only the large editions (27 x 20 cm) were printed by al-misāḥa in Giza (already in 1925 there was a smaller offset printing press in Bulāq ‒ the one in Giza could print large maps). And while the early editions have nothing to do with al-Azhar, in 1952 ʿulemāʾ were involved. BTW, 1952, but before the revolution. 12 line is special, most others in Egypt (Muṣṭafā Naẓīf, aš-Šamarli/Muḥammad Saʿd Ibrāhīm al-Ḥaddād (1919-2011), Haǧǧ Ḥāfiẓ, ʿUṯmān Ḫalīfa QayišZāde an-Nūrī al-Burdurī d. 1894,ʿUṯmān Ṭaha) have 15 lines on a text page, the South African edition on 848 pages has 13 lines; just Pakistan where everything from 9 to 18 lines is common (even 6liner and 21liner exist), produces copies with 12 lines of Arabic text (both with and without interlinear translations).

This edition is also called the “Royal edition” (al-malikiyya or al-amīriyya)This is grammatically impossible, would have to be al-muṣḥaf al-malikī or al-amīrī. In fact the first name is not used for the KFE and the second is short for al-muṣḥaf al-maṭbaʿa al-amīriyya: the Govenment Press Edition. So, here are some of Chahdi's statements ‒ and the facts: first prints in Iran en 1831-1833 ‒ really 1829 in Tehran, '30 in Shiraz, '31 in Tebriz and in Tehran ‒ first type than lithography. en Inde (en 1852) ‒ really in 1829 as Mūẓiḥ al-Qurʾān (with an Urdu translation) and many from than on En Égypte même, on imprime le Coran en 1833 ‒ there exists no trace of this print : it never existed, not even a complete ǧuz L’édition du Caire [1924] est par conséquent la première édition publiée dans le monde arabe ‒ first Cairo edition was 1299/1881/2, many for the next forty years in al-Azhar Library; to my knowledge Faz/Fès where a muṣḥaf was produced in 1879 lies in the Arab world The first complete Qurʾān printed in Cairo is the Bulaq 1299/1881/2 print ‒ both in one volume and in 10 leatherbound parts. It is well known both from the Enyclopedia of the Quran and from Kein Standard: It has 13 lines per page, 603 pages in the one-volume-edition. In 1308/1890 the most important of all Cairo editions was published: "al-Muhallalātī": In 1885 an other important Cairo edition saw the light of day ‒ this one as well with "ar-rasm al-ʿuṯmānī": Let's mention more early "Cairo Editions":

All written by they same calligrapher who wrote the tremendously important 1308/1890 edition, ʿAbd al-Ḫālliq Ḥaqqī Ibn al-Ḫawaǧa, by the editor Šaiḫ Aḥmad bin ʿAlī al-Melīǧī al-Kutbī, who had a press near al-Azhar until 1919. From a copy held in a Catholic Theological Seminar in Frankurt/Main, printed 1315/1898 on 468 pages with 17 lines:

Innahu li-Qurʾān karīm fī kitāb maknūn lā yamassahu illā al-muṭahhirūn tanzīl min ...

Miṣr : al-Maṭbaʻah al-ʻĀmirīyah, 1318 [1900]

364 pp. 19 lines ; 20 cm.

all from before "the first print in the Arab world": « le manuscrit coranique intégralement écrit de la main du savant ... al-Muhallalātī » ‒ was a book printed in 1890 in al-Qāhira (see above and below) La commission mandatée par le roi Fouad est composée d’éminents savants ‒ there was no commission, they never met, they dit not discuss the text of the edition The chief reader قارئ of Egypt Muḥammad ʿAlī al-Ḥusainī al-Ḥaddād was the only Islamic scholar in the "commission"; the other three are from the Minstry of Education or the Pedagogical College next door: Hanafî Nâsif ‒ really Ḥifnī Bey Nāṣif (on his visting card: Nassef) d.1919 ʿAnānī ‒ Muṣṭafā (al-)ʿInānī (d.1362/1943) Aḥmad al-Askandarānī ‒ Aḥmad ibn ʿAlī ibn ʿUmar al-Iskandarī (1292‒1357/1875‒1938) ‒ Ḥifnī Bey Nāṣif died before any work on the edition started. I assume it was mainly his idea; the date given for the signatures is just before his death thus honouring the initiator of the edition. among the countries that have editions of their own Pakistan is mentioned, ‒ but not India, although there were important edition before and after 1947 (in Calcutta, Hooghli, Kanpure, Lucknow, Bombay, Delhi ...) Mais seule l’édition saoudienne de Médine fait vraiment concurrence à celle du Caire ‒ I'd say the opposite: first the KFE was hardly bought by Arabs, but the edition that I call "Uṯmān Ṭaha 1 / UT1" made in Medina is the one that enshrines the text of the KFE albeit the one of the 1952 edition with minor differences le ductus consonantique correspond , schématiquement , au squelette orthographique ‒ orthographique skeleton is fine, but as the Arabic script has letters (not vowels and consonants) the first expression makes no sense La commission pour l’édition du Caire se fonde sur le système de lecture de Hafs Ibn Sulaymân, ou plus précisément sur le manuscrit coranique intégralement écrit de la main du savant égyptien Radwân b. Muhammad al-Muhallalātī ‒ Abū ʿĪd Riḍwān ibn Muḥammad ibn Sulaimān al-Muḫallalātī ( ١٢٥٠-١٣١١/1834-1893) was the editor of the important edition, but the scribe was ʿAbdelḫāliq al-Ḥaqqī Ibn al-Ḫoǧa/Ibn al-Ḫawaǧa; al-Muḫallalātī's edition is important, he broke with the Ottoman orthography, instead followed in some respects the Indian system ‒ and is closer to ad-Dānī's rasm BUT al-Ḥusainī al-Ḥaddād did not follow his orthography, but more the Moroccon (Andalusian, Western) orthography ‒ and is closer to Abu Sulaimān Ibn Naǧāḥ's rasm. And there is something that could be misunderstood: on retrouve [dans les codices anciens] notamment des variantes de lecture extra-canoniques, antérieures à la période de standardisation du corpus coranique. ‒ Marijn van Putten and others have shown that ALL manuscripts follow the ʿUṯmānic rasm (diacritica and voweling non conforming to any of the canonical readings do not amount to differences in the rasm) with the exception of the erased text of the Sanaʾa Palimpsest. If it were « antérieures à la période de standardisation» des qira'āt, riwayāt et ṭuruq, it would have been clearer. ‒ ‒ ‒ ‒ ‒ ‒

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Nairīzī

Mirza Aḥmad an-Nairīzī (ca. 1650–1747) is the last of the classical Iranian calligraher s. Informations are hard to find, because often und...

-

There are several types of madd sign in the Qurʾān, in South Asian masāhif: madd al-muttasil for a longer lengthening of the vowel used...

-

40 years ago Adrian Alan Brockett submitted his Ph.D. to the University of St.Andrews: Studies in Two Transmissions of the Qurʾān . Now...

-

Although it is often written that the King Fuʾād Edition fixed a somehow unclear text, and established the reading of Ḥafṣ according to ʿĀ...