When you want to understand The French Revolution, you should not start with Storming the Bastille,

but with the economic, social and political situation in the decade before.

In order to understand the importance of the King Fuʾād Edition,

we will have a look on the technical side of book printing,

the science of

"rasm and dabṭ",

the calligraphers writing

maṣāḥif.

Let's start with debunking a statement made in the

Muqaddima which was a leaflet put into the KFE.

In it it is stated that the government used to import foreign copies to be used in state schools,

but that these often had to be distroyed because of mistakes. Around 1900 a substantial numbers

had to be buried in the Nile.

I take it for a mystification. Imports came from Bairut, Damascus or Istanbul,

all part of the Ottoman Empire, to which Egypt belonged upto November 1914.

I do not believe a story without exact year, numbers of copies confiscated and a list of mistakes

‒ and who paid how much in compensation to the owner of the books.

In the forty years before the KFE

several times the text of the qurʾān had been type printed in Būlāq:

both in Ottoman Style (eg. صِراط) with

ḥarakāṭ

and

bir-rasm al-ʿUṭmānī: as reported in Dānī's

Muqniʿ, Ibn Naǧāḥ's

Tabyīn

or aš-Šāṭibī's

ʿAqīla without

ḥarakāt (صرط).

Local printers reproduced Ottoman lithographies (written by

Hâfız Osman (1642–1698),

by

Haǧǧ Ḥāfiẓ

ʿUṯmān Ḫalīfa QayišZāde an-Nūrī al-Burdurī d. 1894

or by Muṣṭafā Naẓīf Qadirġālī/ Kadirğali d. 1913 ‒ do not mix up with his fellow calligrapher

Mehmed Naẓīf, who died in the same year) ‒ both with

tafsīr and without.

That something is not the case,

is difficult to prove.

But I declare ‒ whatever others say: A 1833

Būlāq Muṣḥaf does not exist!

Before 1873, in the Ottoman Empire it was forbidden to print a

muṣḥaf.

(For an illegal one

see here.)

Starting 1874 many have been printed in Istanbul ‒ both by private and state presses.

Private printers (notably Muṣṭafā

al-Bābī al-Ḥalabī)

are said to have produced lithograph

maṣāḥif in Cairo starting in the 1860s.

Because no exact years are given, and no name of the calligraphers,

and because in the 1880s more copies of Istanbul lithographs were printed in Cairo than local calligraphers,

I doubt that there were many ‒ anonymous ‒ Egyptian

muṣḥaf writers before the 1880s.

The first Cairo lithograph I have seen is in the Azhar library (several copies there, one in Utah and at least one in Princeton)

In Michael W. Albin's article "Printing of the Qurʾān" in Brill's

Encyclopedia of the Quran

it is mentioned as two different ones: one by the printer Muḥammad Abū Zaid, and one [directed, edited] by Muḥammad Raḍwān [sic].

It is the 1308/1890 copy directed/edited by Abū ʿĪd Riḍwān ibn

Muḥammad ibn Sulaimān al-Muḫallalātī ( ١٢٥٠هـ-١٣١١هـ /

1834-1893), written by ʿAbdelḫāliq al-Ḥaqqī Ibn al-Ḫoǧa/Ibn al-Ḫawaǧa

Both in Istanbul

and Cairo

type set

tafāṣīr with different spellings in the frame and at the margin were published

‒ in Būlāq the unvocalized

rasm at the margin.

Both in large size for the use in Mosques,

gilded, with red as second colour for men of eminence,

and small for craftsmen and housewives

lithographies written by the chief calligrapher of the Ottoman Marine were published.

Foundations, Tombs of Holy Men were offered expensive prints,

schools sets of cheap ones.

Three of his

maṣāḥif are reproduced in other cities:

The one with 15 lines on 522 pages in Bairut, St. Petersburg, Tehran,

in Cairo by ten different publishers ‒ as late as 1954

in the original Ottoman spelling by ʿAlī Yūsuf Sulaimān 1956

sometimes by the minstery of the Interior in the 1924 spelling,

the one with 15 lines on 604 pages in Tehran and Germany with red as additional colour,

in Nusantara in black and white (enriched with the {Indian} sign for /ū/,

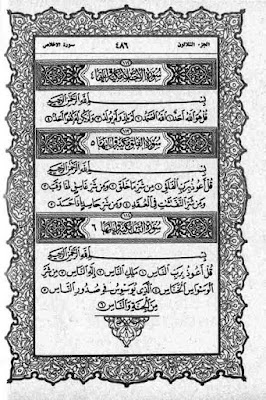

the one with 17 lines on 486 pages in Damascus and by Turks in Germany.

Sometimes with

tafsīr at the margins.

Sometimes with a different orthography.

Until today the version written by Muḥammad Saʿd al-Ḥaddād for aš-Šamarlī ‒ in style very similar to Muṣṭafā Naẓīf and line by line identical to the 522 page version is very popular ‒ a thousand times more popular than the Amiriyya prints, whose 855 page edition was never bought by normal Egyptians: it is no coincidence that the only copies of the original Giza prints survive in Orientalists libraries and studies.

In the 1960s aš-Šamarli had published the original by MNQ in the Q52 orthography (see on the left),

but from 1977 he sold al-Ḥaddād in different sizes, hardcover, plastic and soft;

on the right the original in Ottoman spelling;

Here a Bairūt edition in Q52 with explanations of words on the margin:

Here the Ottoman original

published by Muṣṭafā al-Bābī al-Ḥalābī before MNQ had died (1913)

The 815 page

muṣḥaf by Hafiz Osman (1642-98) was printed in Cairo with one of the bigger Tafsir around, in Syria it was till about 1960

the muṣḥaf

Here pages 2 + 3 from the Cairo print (without the commentary)

At least until islamist Qaṭar supplied islamist forces in Syria with arms and money

thus starting a bitter "civil" war, in Aleppo "Ottoman" parts of the Qurʾān were printed:

and until 1990 in al-ʿIrāq two Ottoman

maṣāḥif were printed by the state.

in the Turkish Republic only expensive facsimiles reproduce old manuscripts,

"reprints" for believers are heavily edited.

In 1370/1951 the ʿIrāqi Dīwān al-ʾAuqāf had it printed under the

supervision of Naǧmaddīn al-Wāʾiz with Kufi numbers after each verse and sura title boxes written

by Hāšim Muḥammad al-Ḫaṭṭāt al-Baġdādī,

1386/1966 for the ʿirāqī state by Lohse in Frankfurt/Main,

1398/1978 for the suʿūdī government in West Germany,

1400/1979 in Qaṭar, 1401/1981 for Ṣaddām.

In 1236 Muḥammad Amīn ar-Rušdī had written the original

muṣḥāf. In 1278 ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz's

mother offered it to the tomb of

Junaid in Baghdād. Today it is kept in the library

of the tomb of

Abu Ḥanīfa.

Whereas in the manuscript ‒ as I guess ‒

waṣl-sign were only on

alifs before sun-letters,

in the ʿIrāqi print most initial

alifs have one, which leads to the annomaly that

sometimes an

alif has both "waṣl" underneath and a

waṣl-sign above.

After every tenth verse a

yāʾ (in the

abjad system: ten) hovers before the number (see above); what was helpful

in the original manuscript that had only end-of-verse-markers, is kind of ridiculous

in the printed edition.

Of interest as well:

"bi-yāʾ wāhida" under

riyyīn in 5:111,

which in another Ottoman

muṣḥaf is written yāʾ +

šadda + turned

kasra +

yāʾ and in the mordern Turkish ones with one

yāʾ and in Q24

with a normal

yāʾ plus a high small one.

Brockett studied in Edinburgh an Ottoman Manuscript from 1800, in which under 41:47

bi-ʾaidin bi-yāʾain is written. How-to-write-notes were common (in the same Ms. in 43:3 under a hamza-letter

"bi-ġair alif" is written.

The Dīwān al-auqāf published ‒ with similar front and back matter ‒ reprints by

Ḥafiz ʿUṯmān and Ḥasan Riḍā.

on the right the cover of the M.A. ar-Rušdī edition,

in the middle Ḥasan Riḍā, on the left the editor. ‒ After the US-intervention

there are two authorities:

Dīwān al-waqf as-sunnī and

... aš-šiʿī, both published

maṣāḥif on 604 pages:

the Sunni took the text from KFC (UT1, cf

Kein Standard), the Ši'i had the ʿirāqī

Calligrapher,

Hādī ad-Darāǧī, write it.

In anear

lier

post (and above) I retold the history of the manuscript and its prints.

Except for the backmatter and the division into

aḥzāb they are all the same:

al-Wāʾiz's edition

Recently I learned that in 1415/1994 an Iranian reprint was made ‒ not based on the manuscript but on the ʿirāqī version.

While the

ihmal-sign were deleted already in 1370/1951, forty years later other "confusing" stuff had to go:

‒ high

yāʾ barī for every tenth verse,

‒ the differentiation between leading alif followed by a

ḥarf sākin

and others ‒ now ALL alifs-waṣl have a

waṣl-sign (head of صـ)

‒ signs for pauses or vowels are placed nearer to "their" base letter

‒ sometimes the space between words is enlarged, a swash nūn replaced by a normal one

‒ a normal

ḍamma-sign was replaced by a turned one, where it is pronouinced ū (due to rules of prosody)

‒ Mūsā gets a long-

fatḥa,

Is there someone who has images of the manuscript?

on the right the first "normal" page of Muḥ. ʾAmīn ar-Rušdī's

muṣḥaf, on the left: Ḥasan Riḍā:

Remarkable below:

‒ in lignes 3,5,6,7,9: the boundary

between words is between alifs

‒ in lign 2: before (10) a small high yāʾ, which in the manucrpt was needed to signal: 10

‒ some Ihmal-signs below letter signalling: without dot

> ... es sei denn du fast ihn selbst "verbessert"!

Haǧǧ Ḥāfiẓ ʿUṯmān Ḫalīfa QayišZāde an-Nūrū al-Burdurī (Hac Hattat Kayışzade Hafis Osman Nuri Efendi Burdurlu) schrieb 106 1/2

maṣāḥif.

Den auf 815 Seten (ohne das Abschlussgebet, den Index und das Kolophon) ist sehr oft und sehr lange in Syrien

(und auch in Ägypten allein oder mit

tafsīr) nachgedruckt worden, einen der 604seitigen gibt es immer noch in der Türkei.

Links ein Damaszener Druck vor 1950 mit vielen Zeichen, die später getilgt wurden:

kleines

hā' und

yā' für Fünf und Zehn (15,20, 25,30 ...)

zwei Kleinbuchstaben (immer eines davon

bā') über baṣrische Verszählung

kleine punktlose Buchstaben unter oder über einem punktlosen Buchstaben, um zu betonen, dass da kein Punkt fehlt

(oder auch لا, was wie ein V oder VogelFlügel aussieht ‒ in manchen Manuskripten bekommen

dāl und

rāʾ

einen Punkt darunter, um zu sagen nicht

-zāʾ, nicht

-ḏāl).

In der Mittel (auf blassgrünem Grund) habe ich zwei Stellen hervorgehoben:

bei der ersten haben die modernen türkischen Bearbeiter (siehe rechts /gelblich)

die zwei Wörter von anderen Stellen im

muṣḥaf hierhinkopiert, damit es klar und deutlich von Rechts nach links geht,

damit jedes Vokalzeichen "richtig" platziert ist.

bei der zweiten Stelle haben sich die Herausgeber an dem 815er

muṣḥaf bedient, um den

rasm zu "korrigieren":

beginning of verse 94 of Ṭaha 94:

Modern editors often improve old manuscripts.

In Ottoman mss. there are

waṣl-signs on alifs ONLY before an unvowelled letter

‒ most of the time before the

lām of the article before a sun-letter.

Modern Iranian reprint editors put

waṣl-signs wherever one puts them according to modern rules.

Turkish editors follow the Indian practise: no

waṣl-signs (vowel-sign includes

hamza, no sign IS

waṣl)

In the mss. wau

-hamza stands sometimes for wau

plus hamza.

When the wau is ONLY

hamza-carrier, sometimes ‒ when a misreading is deemed likely ‒ one finds

qṣr under the wau.

Now in Turkey,

always when it is not

ḥarf al-madd plus hamza, one finds the reading help ‒ and

madd underneath when it is both hamza and /ū/.

Modernity demands clarity: either always (Iran) or never (Turkey).

Ḥasan Riḍā and Muḥ ar-Rušdī (second and forth line of ʿiraqī prints with verse numbers and title boxes) have no "qiṣr" seeing no danger that one could read it /ūʾ/.

1a) Diyanet gets ridd of all "confusing" signs.

In the first line (of a "14th" print of a Hafiz Osman

muṣḥaf, 1987) there is still a

waṣl-sign (more clearly in the third line ‒ an Hafiz Osman original ‒

now it is gone.

I guess that the Diyanet editor did not realized that the (now missing)

alif-waṣl reminds of

Ibn.

2.) Diyanet moves slightly from the Ottoman practise to the Suʿudi standard (Q52).

Here they follow ad-Dānī: three (real) word as one.

In his 1309er (hiǧri)

muṣḥaf (last line before the computer set one) Hafiz Osman had written "oh, mother's son" in one word.

Diyanet has established a standard of 604/5 pages, often moves word or letters to make old manuscripts according to the new set.

In the forty years before the KFE several times the text of the qurʾān had been type printed in Būlāq:

(eg. صِراط) with

(صرط).

d. 1894

or by Muṣṭafā Naẓīf Qadirġālī/ Kadirğali d. 1913 ‒ do not mix up with his fellow calligrapher Mehmed Naẓīf, who died in the same year) both with tafsīr and without.