Ik bedoel jou, de beste Curanoloog, als wat er met Gotthelf, Otto, Theo en Pim is gebeurd, niet met jou gebeurt.

Als het op transcriberen aankomt, ben je erg precies. Als het gaat om edities, drukken, versies, recensies, ben je slordig.

editie betekent = "bepaalde druk van een ... boek"

uitgave, exemplaren die in één keer gedrukt worden, druk van een boek

1) Aantal gedrukte exemplaren 2) Aantal te drukken exemplaren 3) Aflevering 4) Boekuitgave 5) Deel van een krantenoplage 6) Druk 7) Druk van een boek 8) Oplaag 9) Oplaag van een boek 10) Oplage 11) Oplage van boeken

Is verschillend van "teksteditie/ tekstuitgave".

edition = The entire number of copies of a publication issued at one time or from a single set of type. / The entire number of like or identical items issued or produced as a set

Édition (Nom commun)

[e.di.sjɔ̃] / Féminin

Impression, publication et diffusion d’une œuvre artistique (livre, musique, objet d’art, etc). soit qu’elle paraisse pour la première fois, soit qu’elle ait déjà été imprimé ; ou les séries successives des exemplaires qu’on imprime pour cette publication.

Totalité des exemplaires de tel ou tel ouvrage publié et mis en vente.

Par extension, l’industrie qui a pour objet la publication d’ouvrage.

Tirage spécifique de la même édition d’un ouvrage.

Exemplaire faisant partie d’un tirage dans une édition.

(Journalisme) Tirage strictement identique de l’édition du jour d’un quotidien.

In het Frans is het bijzonder duidelijk: « maison d'édition » betekent een uitgeverij.

"editie" is niet wat an editor/een redacteur doet, maar wat an publisher/een uitgever doet.

Als je naar klassieke Arabische werken kijkt, waren er tot voor kort meestal twee of drie edities: één uit Leiden en één uit Cairo, één uit Göttingen en één uit Oxford. Hier, "the Cairo edition" maakt geen probleem.

Maar met de Koran is het anders: er zijn tegenwoordig duizenden edities. Alleen al uit Cairo zijn er tien belangrijke uitgaven van de Warš lezing.

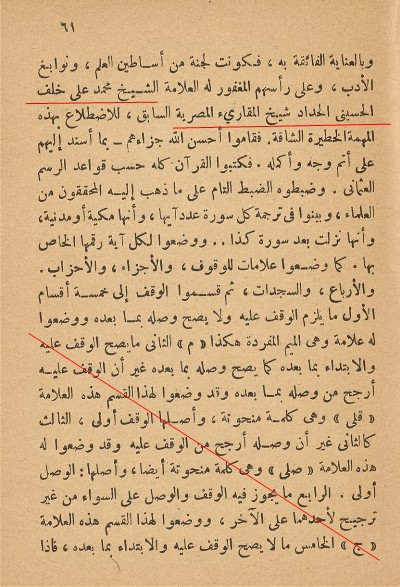

Here two images from a 1929 Cairo Warš Edition ‒ without a title page, as was common at the time:

And here from two of the oldest al-Qahira publishers, i.e. not from Bab al-Khalq, al-Faggala, from Bulaq or even Giza but from "behind" al-Azhar:

Apart from these 100% Cairo Editions, there are editions conceaved in Morocco resp. Algeria,

but produced in Cairo ‒ the Moroccan ones without production place, the Algerian ones with an

Algerian publisher's name. (Only the third edition of the third sherifian muṣḥaf was

produced in Morocco.)

Er is niet meer "de editie van Caïro" dan er "de Ayatollah" of "de roman van Parijs" is.

Alleen drukwerkspecialisten zijn geïnteresseerd in drukwerk (hoeveel regels per pagina, hoeveel pagina's per ǧuz, aanduiding van chronologie, saǧadat, sakatāt, typografie, kalligrafie...). Curanaloogen zijn geïnteresseerd in de rasmen, de verzendingen, de orthografie.

Zelfs als we alleen kijken naar de belangrijkste Ḥafṣ uitgaven, zijn er enkele uit 1881, 1890, 1924, 1952, 1975, 1976. Zelfs de uitgaven van de Amīriyya uit 1926 en 1929 verschillen van de Gizeh-prent uit 1924.

Ik weet niet welke editie bedoeld wordt ‒ zou kunnen bedoeld worden ‒ met "cairo edition".

Ik heb de indruk dat u de Uthman rasm bedoelt, het gebruikelijke schrift zonder extra alifen, dat gebruikelijk werd in het Ottomaanse Rijk en Iran.

De prent van Gizeh uit 1924 is bijna nergens in de islamitische wereld te vinden, maar vaak wel in Duitse, Nederlandse en Zwitserse bibliotheken.

80% van de Moslims gebruiken totaal verschillende uitgaven, zij het verschillende lezingen, zij het verschillende spellingen. Tot in de jaren tachtig gebruikten de Arabers van Mašriq ook overwegend Ottoaanse edities.

Tegenwoordig gebruiken veel Arabieren, Maleisiërs en Salafisten edities in de spelling van de 1952 editie van de Koran, maar alleen Oriëntalisten hebben ooit de Amīriyya editie gebruikt.

Een derde van de moslims is afkomstig van het Indiase subcontinent, zodat Indiase kwesties wereldwijd het meest voorkomen.

Bijna een zesde van de moslims gebruikt Indonesische edities.

Turkije heeft zijn eigen standaard, Iran heeft er meerdere.

Saturday, 6 November 2021

Thursday, 4 November 2021

Mistake in the Andalusian/Maghribi/Arab Style

One of the errors in the 1924 Qur'an that Indians, Indonesians, Persians and Turks take exception to is that "God" is written with a short a: ʾallah instead of ʾaḷḷāh.

In "Kein Srandard" I call that a clear mistake.

But what is 100% clear?

The Arab advocates of the 1924 reform might say:

Even Ibn al-Bawwāb wrote like this I reply:

yes, but raḥmān is also with short a and ḏālika too.

I reply:

yes, but raḥmān is also with short a and ḏālika too.

If there is no long /ā/ sign in the whole codex,

then you don't need one in ʾaḷḷāh.

But in the Giza Qur'an there is Long-ā (fatḥa + dagger-alif) everywhere where needed!

As explained in "Kein Standard" Bergsträßer and experts have overlooked that

the 1924 orthography is not an invention, but just copied from a Warš muṣḥaf:

If there is no long /ā/ sign in the whole codex,

then you don't need one in ʾaḷḷāh.

But in the Giza Qur'an there is Long-ā (fatḥa + dagger-alif) everywhere where needed!

As explained in "Kein Standard" Bergsträßer and experts have overlooked that

the 1924 orthography is not an invention, but just copied from a Warš muṣḥaf:

And just as these do not spell ʾaḷḷāh correctly

but incorrectly,

And just as these do not spell ʾaḷḷāh correctly

but incorrectly,

so does G24 and since 1990 all Arabs (esp. Madina).

At least, they write ʾallah all the time:

instead of ʾaḷḷāh:

the Nizām of Hyderabad had it corrected (1938, reprinted by the Islamic Call Society 1976f.):

but not in allahumma (nowhere, and in none of the bilingual editions ‒ cf. first line)

so does G24 and since 1990 all Arabs (esp. Madina).

At least, they write ʾallah all the time:

instead of ʾaḷḷāh:

the Nizām of Hyderabad had it corrected (1938, reprinted by the Islamic Call Society 1976f.):

but not in allahumma (nowhere, and in none of the bilingual editions ‒ cf. first line)

Two examples from Dalīl al-Ḫairāt, one from Mali without long /ā/, one from the Ottoman Empire with long /ā/:

I reply:

yes, but raḥmān is also with short a and ḏālika too.

I reply:

yes, but raḥmān is also with short a and ḏālika too.

If there is no long /ā/ sign in the whole codex,

then you don't need one in ʾaḷḷāh.

But in the Giza Qur'an there is Long-ā (fatḥa + dagger-alif) everywhere where needed!

As explained in "Kein Standard" Bergsträßer and experts have overlooked that

the 1924 orthography is not an invention, but just copied from a Warš muṣḥaf:

If there is no long /ā/ sign in the whole codex,

then you don't need one in ʾaḷḷāh.

But in the Giza Qur'an there is Long-ā (fatḥa + dagger-alif) everywhere where needed!

As explained in "Kein Standard" Bergsträßer and experts have overlooked that

the 1924 orthography is not an invention, but just copied from a Warš muṣḥaf:

And just as these do not spell ʾaḷḷāh correctly

but incorrectly,

And just as these do not spell ʾaḷḷāh correctly

but incorrectly,

so does G24 and since 1990 all Arabs (esp. Madina).

At least, they write ʾallah all the time:

instead of ʾaḷḷāh:

the Nizām of Hyderabad had it corrected (1938, reprinted by the Islamic Call Society 1976f.):

but not in allahumma (nowhere, and in none of the bilingual editions ‒ cf. first line)

so does G24 and since 1990 all Arabs (esp. Madina).

At least, they write ʾallah all the time:

instead of ʾaḷḷāh:

the Nizām of Hyderabad had it corrected (1938, reprinted by the Islamic Call Society 1976f.):

but not in allahumma (nowhere, and in none of the bilingual editions ‒ cf. first line)

Two examples from Dalīl al-Ḫairāt, one from Mali without long /ā/, one from the Ottoman Empire with long /ā/:

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Nairīzī

Mirza Aḥmad an-Nairīzī (ca. 1650–1747) is the last of the classical Iranian calligraher s. Informations are hard to find, because often und...

-

There are several types of madd sign in the Qurʾān, in South Asian masāhif: madd al-muttasil for a longer lengthening of the vowel used...

-

40 years ago Adrian Alan Brockett submitted his Ph.D. to the University of St.Andrews: Studies in Two Transmissions of the Qurʾān . Now...

-

Although it is often written that the King Fuʾād Edition fixed a somehow unclear text, and established the reading of Ḥafṣ according to ʿĀ...