While India has a long tradition of spelling maṣāḥif,

there is one šaiḫ, Ẓafār Iqbāl as-Sīālkōtī, who published a mix of Indian and African spelling:

he keeps the long vowel signs

he adds hamza sign (which in IPak is included in vowel sign)

he adds differenciated tanwin signs (an improvement, but not necessary: determined by the following letter)

he does not differentiate between ī and ĭ (determined by the following letters)

he has both the normal ǧazm/head of ǧim without dot and the "Calcutta" angle for sukūn (why?)

Showing posts with label Indo-Pak. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Indo-Pak. Show all posts

Monday, 7 April 2025

Sunday, 22 December 2024

No Standard ‒ Main Points

there is no standard copy of the qurʾān.

There are 14 readings (seven recognized by all, three more, and four (or five) of contested status).

there are 14 canonical transmissions (riwājāt) (two of each of the Seven),

each of which has ways/paths (ṭuruq) and versions/faces (wuǧuh).

All of this is not our main interest, because

‒ except in the greater Maghrib, Sudan, Somalia and Yaman and among the Bohras ‒

rank and file Muslims read only one riwāja: Ḥafṣ ʿan ʿĀṣim.

The second big difference between copies of the qurʾān that does not interest us here,

is the rasm: there are three main rasm authorities to follow: ad-Dānī, Ibn Naǧāḥ, al-Ḫarrāz, and al-Ārkātī

As far as I know most editions follow a mix of diverent authorities ‒ the Lybian Qālūn Edition (muṣḥaf al-jamāhīriya, 1987, second ed. 1989, Libyan after the death of the prophet 1399) following ad-Dānī being an exception.

Authorities in Iran and Indonesia publish lists where they follow whom, others just have their (secret) way.

What interests me is

the spelling and

the layout.

Other points are important, like the

pauses and

the divisions (juz, ḥizb, para, manzil, niṣf ...),

but I do not know enough to post about them.

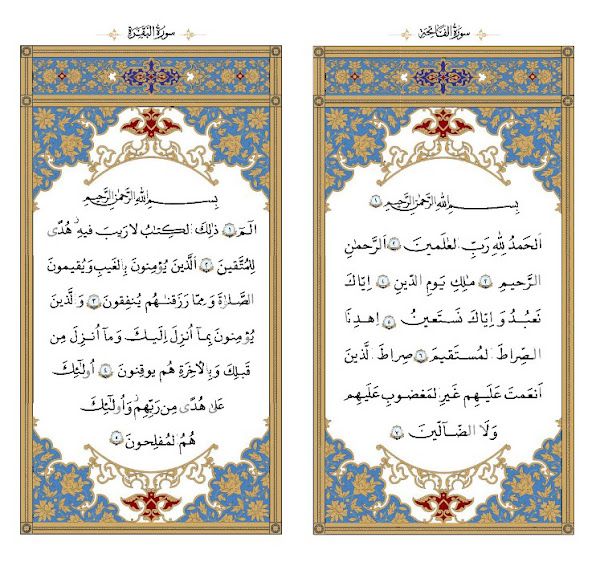

There are two main spellings: western and eastern

IPak is THE eastern spelling;

Ottoman, Persian, Turk, Tartar, NeoIran, Indonesian are eastern sub-spellings.

G24 and Q52 are realisation of the western spelling, Mag being their "mother".

The main difference between West and East is the writing of long vowel.

While in the East the (short) signs are turned to make them long,

in the West a lengthening vowel has to follow: either one that is part of the rasm or a small substitute.

G24/Q52 differentiate between /a/ and /ā/, but not between /i/ and /ī/ when there is a yāʾ in the text.

IPak always makes the difference.

(just to make clear: in the middle column, in /hāḏā/ the dagger in IPak is a vowel sign, in Mag it is a small letter lengthening the sign before it ‒ although they look the same, they are different things)

Mag, G24, Q52 have three kinds of tanwin, Bombay instead has izhar nun, IPak, Osm ... have nothing

Maybe the most remarkable difference are the initial alif: the Africa they have ḥamza-sign or a waṣl-sign.

In Asia a voyell-sign includes ḥamza, absence of all sign signifies "mute" or waṣl.

Because letters without any sign the four yāʾs in the three lines standing for ī need a sukūn not to be ignored.

all in all: a large part of the letters have a different sign in Africa and Asia.

Another differences lies in assimilation: both Mag and IPak do mark assimilation, Osm, Turk, Pers, NIran do not. While IPak has three different madd signs, Mag/G24/Q52 have only one. The main feature of page layout is the number of lines per page. Leaving the layout with a page for a thirtieth or sixtieth on the side there are layouts with nine to twenty lines per page, the berkenar with 604 pages of 15 lines being the most common (due to Hafiz Osman and ʿUṯmān Ṭaha). My motivation was anger about old German orientalists calling the King Fuʾād Edition "the Standard Edition"; later I came across young orientalist calling it "CE" / "the Cairo Edition", althought there are more than a thousand maṣāḥif printed in Cairo, more than a hundred conceived in Cairo, so calling one of these the "CE" is madness, ignorance, carelessness. The only new thing about the KFE: it is type set, but offset printed; its text is not new, but a switch. It turns out that there are different KFEs, 27 cm high ones printed 1924, 1925, 1952, 1953 in the Survey of Egypt in Giza, later in the press of Dar al-Kutub in Gamāmīz, and 20 cm high oneS printed in Būlāq; there is one written by Muḥammad ibn ʿAlī ibn Ḫalaf al-Ḥusainī al-Mālikī aṣ-Ṣaʿīdī al-Ḥaddād and one revised under the guidance of ʿAlī b. Muḥammad b. Ḥasan b. Ibrāhīm al-Maṣrī aḍ-Ḍabbāʿ. The text of 1924 is history, the text of 1952 survives in the "Shamarly" written by Muḥammad Saʿd Ibrāhīm al-Ḥaddād and in the Ḥafṣ 604 page maṣāḥif written by ʿUṯmān Ṭaha. The Amīriyya itself printed the text of 1952 in the large KFE printed in Gamāmīz and the Muṣḥaf al-Azhar aš-Šarīf (with four in-between-pause-signs merged into one) printed in Būlāq; but their small kfes have the '24 text with a few '52 changes ‒ a strange mix that stayed largely unnoticed. Just as there are seven different KFE/kfe, there are four different UTs: UT0 1399‒1404 with (up to) five mistakes, basically KFE II, without afterword ‒ printed in Damascus, Istanbul, Tehran UT1 1405‒1421 without mistakes, with a dagger under hamza in 2:72, and the small sīn under ṣād eliminated in 8:22 ("photoshopded") ‒ first with the 1924 afterword, later with "mostly" added ‒ printed in Madina and many places UT2 1422‒'38 without space between words and no leading between lines (written by UT in Madina) ‒ and printed in Madina UT3 since 1438 without headers at the bottom of pages, without end if aya at the beginning of lines, with corrected sequential fathatan ‒ rearranged and printed in Madina When you compare UT2 (above) with UT3 you see: they are very similar; but while there are small differences between the same words in UT2 the same word in UT3 is identical. Another difference: in UT2 sometimes there is zero space between words; that does not occur in UT3. ‒

Because letters without any sign the four yāʾs in the three lines standing for ī need a sukūn not to be ignored.

all in all: a large part of the letters have a different sign in Africa and Asia.

Another differences lies in assimilation: both Mag and IPak do mark assimilation, Osm, Turk, Pers, NIran do not. While IPak has three different madd signs, Mag/G24/Q52 have only one. The main feature of page layout is the number of lines per page. Leaving the layout with a page for a thirtieth or sixtieth on the side there are layouts with nine to twenty lines per page, the berkenar with 604 pages of 15 lines being the most common (due to Hafiz Osman and ʿUṯmān Ṭaha). My motivation was anger about old German orientalists calling the King Fuʾād Edition "the Standard Edition"; later I came across young orientalist calling it "CE" / "the Cairo Edition", althought there are more than a thousand maṣāḥif printed in Cairo, more than a hundred conceived in Cairo, so calling one of these the "CE" is madness, ignorance, carelessness. The only new thing about the KFE: it is type set, but offset printed; its text is not new, but a switch. It turns out that there are different KFEs, 27 cm high ones printed 1924, 1925, 1952, 1953 in the Survey of Egypt in Giza, later in the press of Dar al-Kutub in Gamāmīz, and 20 cm high oneS printed in Būlāq; there is one written by Muḥammad ibn ʿAlī ibn Ḫalaf al-Ḥusainī al-Mālikī aṣ-Ṣaʿīdī al-Ḥaddād and one revised under the guidance of ʿAlī b. Muḥammad b. Ḥasan b. Ibrāhīm al-Maṣrī aḍ-Ḍabbāʿ. The text of 1924 is history, the text of 1952 survives in the "Shamarly" written by Muḥammad Saʿd Ibrāhīm al-Ḥaddād and in the Ḥafṣ 604 page maṣāḥif written by ʿUṯmān Ṭaha. The Amīriyya itself printed the text of 1952 in the large KFE printed in Gamāmīz and the Muṣḥaf al-Azhar aš-Šarīf (with four in-between-pause-signs merged into one) printed in Būlāq; but their small kfes have the '24 text with a few '52 changes ‒ a strange mix that stayed largely unnoticed. Just as there are seven different KFE/kfe, there are four different UTs: UT0 1399‒1404 with (up to) five mistakes, basically KFE II, without afterword ‒ printed in Damascus, Istanbul, Tehran UT1 1405‒1421 without mistakes, with a dagger under hamza in 2:72, and the small sīn under ṣād eliminated in 8:22 ("photoshopded") ‒ first with the 1924 afterword, later with "mostly" added ‒ printed in Madina and many places UT2 1422‒'38 without space between words and no leading between lines (written by UT in Madina) ‒ and printed in Madina UT3 since 1438 without headers at the bottom of pages, without end if aya at the beginning of lines, with corrected sequential fathatan ‒ rearranged and printed in Madina When you compare UT2 (above) with UT3 you see: they are very similar; but while there are small differences between the same words in UT2 the same word in UT3 is identical. Another difference: in UT2 sometimes there is zero space between words; that does not occur in UT3. ‒

Sunday, 14 April 2024

a book by Saima Yacoob, Charlotte, North Carolina

At the start of this year's Ramaḍān Saima Yacoob, Charlotte, North Carolina published a book on differences between printed maṣāḥif. Although her starting point and her conclusions are worthy, the book is full of mistakes.

Let's start with the positive:

• I believe that it would be a great loss to our ummah if we were to insist on abandoning [the existing] diversity [in] apply[ing] the rules of ḍabṭ ... • The framework of the science of ḍabṭ is that diacritics be used to ensure that the Qurʾān can be recited correctly by the average Muslim, and that there is enough regional standardization ... that the people of an area may read the Qurʾān correctly through the maṣāḥif published ... in that area. • Because of the flexibility [in] the science of ḍabṭ, new conventions of ḍabṭ may be added even today to meet the changing needs of Muslims in a particular region. A modern example of this is the tajwīd color coded maṣāḥif.This is an important point: maṣāḥif do not have to be identical to be valid. Only the last remark is wrong: color coded maṣāḥif are not "particular [to a] region". I will give an example that springs from a particular region: The Irani Muṣḥaf with simple vowel signs: While we used to have two basic ways of writing vowels (the Western/"African" with three vowel signs, sukūn, and three small lengthening letters, the Eastern/"Asian" with three short vowel signs, three long vowel signs, and sukūn/ǧasm)); now there is a third (the new "Iranian" with six vowel signs in which the sign for /ū/ is not a turned ḍamma as in Indo-Pak and Indonesia, but looks like the Maġribian/Afro-Arab small waw, without sukūn, but with a second color for "silent, unpronounced"): Only the vowel signs count, vowel letters are ignored when the consonant before has a vowel sign and they have none; when a consonant has no vowel sign it is read without vowel (sukūn is not needed). When a "vowel letter" has a vowel sign, it is a consonant. There is no head of ʿain on/below alif (when there is a vowel sign, hamza is spoken). There are no small vowel lettes ‒ instead of "turned ḍamma/ulta peš" a small waw is used: it look like the small letter used in the West/Maghrib/Arab Countries, but is a vowel sign. The main point of Differing Diacritics is: there are different ways to mark the fine points, and that's okay. The maṣāḥif have the same text, but the notation is not exactely the same. On page 2 of the book the diactrics are defined. Šaiḫa Saima Yacoob states that there are three kinds: 1.) "letters that are additional or omitted in the rasm" 2.) "fatḥah, kasrah, ḍammah, shaddah, etc." "Thirdly, those markings that aid the reader to apply the general rules of tajwīd correctly, such as the sign for madd, or a shaddah that indicates idghām, etc." ALL wrong. First come the dots that distinguish letter with the same shape: د <‒>ذ ص <‒> ض ب <‒> ن ي ط <‒> ظ Second: fatḥa, kasra, ḍamma, šaddah, sukūn, plus in "Asia" turned fatḥa, turned kasra, turned ḍamma Third: tanwīn signs and signs for madd ‒ in Asia there are three kinds of madd signs, in "Africa" three kinds of tanwīn signs for each of the short vowels ‒ small vowel "letters that are additional or omitted in the rasm" exist only in the African/Andalusian/Arab system the tiny groups of small consonant letters (sīn, mīm, nūn) that modify pronounciation, and the signs for išmām and imāla come fourth and fifth. (In Turkey "qaṣr" and "madd" are a sixth group.) On page 4 the šaiḫa writes: "the reader could easily get confused by the two sets of dots, those for vowels, and those that distinguished similarly shaped letters from each other" I disagree: the dots for vowels are in gold/yellow, green, red or blue (and usually big), those distinguishing letters with the same base form are in black (like the letters, because they are part of the letters). How can one confuse (big) coloured and (smaller) black dots? BTW, "distinguished similarly shaped letters from each other" ‒ what I called the first function of diacritics ‒ is missing from her definition of ḍabṭ on page 2. Yacoob sometimes repeats what is written in well known books, but makes no sense: "symbols [for vowels] were taken from shortened versions of their original form, such as ... a portion of yāʾ for kasrah" (p.4). While fatḥa and ḍamma look like small alif resp. waw, kasra is neither a shortened yāʾ nor a part of yāʾ ‒ to me it looks like a transposed fatḥa.

Unfortunately, I found very little information about the ḍabṭ of the South Asian muṣḥaf in Arabic. (p. 7)okay, she did not find anything, but it is available and it is all in Arabic (although written by a Muslim from Tamil Nadu).

the Chinese muṣḥaf. (p. 7)As far as I know, there is no printed Chinese muṣḥaf, definetly not "the Chinese muṣḥaf". I have two maṣāḥif from China: a Bejing reprint of the King Fuad Edition of 1924/5 and a Kashgar reprint of the Taj edition with the text on 611 pages like the South Asian one printed by the King Fahd Complex. That a reprint of a Taj edition follows the IndoPak rules goes without saying, but that is not "the Ch. m."! Enough, it goes on like this: mistake after mistake. I don't understand how a careful person can write a book like this ‒ and not revise it in due course.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Nairīzī

Mirza Aḥmad an-Nairīzī (ca. 1650–1747) is the last of the classical Iranian calligraher s. Informations are hard to find, because often und...

-

There are several types of madd sign in the Qurʾān, in South Asian masāhif: madd al-muttasil for a longer lengthening of the vowel used...

-

40 years ago Adrian Alan Brockett submitted his Ph.D. to the University of St.Andrews: Studies in Two Transmissions of the Qurʾān . Now...

-

Although it is often written that the King Fuʾād Edition fixed a somehow unclear text, and established the reading of Ḥafṣ according to ʿĀ...