At the start of this year's Ramaḍān Saima Yacoob, Charlotte, North Carolina published

a book on differences between printed

maṣāḥif. Although her starting point and her conclusions are worthy, the book is full of mistakes.

Let's start with the positive:

• I believe that it would be a great loss to our ummah if we were to insist on abandoning [the existing] diversity [in] apply[ing] the rules of ḍabṭ ...

• The framework of the science of ḍabṭ is that diacritics be used to ensure that the Qurʾān can be recited correctly by the average Muslim, and that there is enough regional standardization ... that the people of an area may read the Qurʾān correctly through the maṣāḥif published ... in that area.

• Because of the flexibility [in] the science of ḍabṭ, new conventions of ḍabṭ may be added even today to meet the changing needs of Muslims in a particular region. A modern example of this is the tajwīd color coded maṣāḥif.

This is an important point:

maṣāḥif do not have to be identical to be valid. Only the last remark is wrong: color coded

maṣāḥif are not "particular [to a] region".

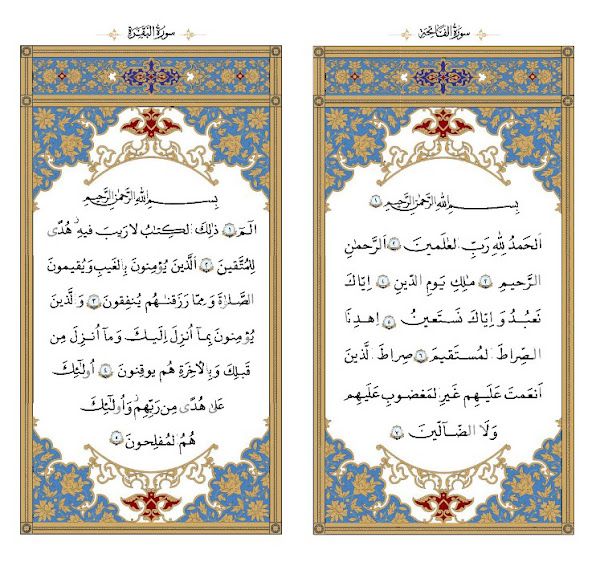

I will give an example that springs from a particular region: The

Irani Muṣḥaf with simple vowel signs:

While we used to have two basic ways of writing vowels (the Western/"African" with three

vowel signs,

sukūn, and three small lengthening

letters, the Eastern/"Asian" with three

short vowel signs, three

long vowel signs, and

sukūn/ǧasm)); now there is a third (the new "Iranian" with six vowel signs in which the

sign for /ū/ is not a turned

ḍamma as in Indo-Pak and Indonesia, but

looks like the Maġribian/Afro-Arab small waw, without

sukūn, but with a second color for "silent, unpronounced"):

Only the vowel

signs count, vowel

letters are ignored when the consonant before has a vowel

sign and they have none; when a consonant has no vowel sign it is read without vowel

(sukūn is not needed). When a "vowel letter" has a vowel sign, it is a consonant. There is no head of ʿain on/below alif (when there is a vowel sign, hamza is spoken). There are no small vowel lettes ‒ instead of "turned ḍamma/ulta peš" a small waw is used: it look like the small

letter used in the West/Maghrib/Arab Countries, but is a vowel

sign.

The main point of

Differing Diacritics is: there are different ways to mark the fine points, and that's okay. The

maṣāḥif have the same text, but the notation is not exactely the same.

On page 2 of the book the diactrics are defined. Šaiḫa Saima Yacoob states that there are three kinds:

1.) "letters that are additional or omitted in the

rasm"

2.)

"fatḥah, kasrah, ḍammah, shaddah, etc."

"Thirdly, those markings that aid the reader to apply the general rules of

tajwīd correctly, such as the sign for

madd, or a shaddah that indicates

idghām, etc."

ALL wrong.

First come the dots that distinguish letter with the same shape:

د <‒>ذ

ص <‒> ض

ب <‒> ن ي

ط <‒> ظ

Second:

fatḥa, kasra, ḍamma, šaddah, sukūn, plus in "Asia" turned

fatḥa, turned

kasra, turned

ḍamma

Third:

tanwīn signs and signs for

madd ‒ in Asia there are three kinds of

madd signs, in "Africa" three kinds of

tanwīn signs for each of the short vowels

‒ small vowel "letters that are additional or omitted in the

rasm" exist only in the African/Andalusian/Arab system

the tiny groups of small consonant letters (sīn, mīm, nūn) that modify pronounciation,

and the signs for

išmām and

imāla come fourth and fifth.

(In Turkey "qaṣr" and "madd" are a sixth group.)

On page 4 the šaiḫa writes: "the reader could easily get confused by the two sets of dots, those for vowels, and those that distinguished similarly shaped letters from each other"

I disagree: the dots for vowels are in gold/yellow, green, red or blue (and usually big), those distinguishing letters with the same base form are in black (like the letters, because they are part of the letters). How can one confuse (big) coloured and (smaller) black dots?

BTW, "distinguished similarly shaped letters from each other" ‒ what I called the first function of diacritics ‒ is missing from her definition of

ḍabṭ on page 2.

Yacoob sometimes repeats what is written in well known books, but makes no sense:

"symbols [for vowels] were taken from shortened versions of their original form, such as ... a portion of yāʾ for

kasrah" (p.4).

While

fatḥa and

ḍamma look like small alif resp. waw,

kasra is neither a shortened yāʾ nor a part of yāʾ ‒ to me it looks like a transposed

fatḥa.

Unfortunately, I found very little information about the ḍabṭ of the South Asian muṣḥaf in Arabic. (p. 7)

okay, she did not find anything, but it is

available and it is all in Arabic (although written by a Muslim from Tamil Nadu).

the Chinese muṣḥaf. (p. 7)

As far as I know, there is no printed Chinese

muṣḥaf, definetly not "the Chinese

muṣḥaf". I have two

maṣāḥif from China: a Bejing reprint of the King Fuad Edition of 1924/5 and a Kashgar reprint of the

Taj edition with the text on 611 pages like the South Asian one printed by the King Fahd Complex. That a reprint of a Taj edition follows the IndoPak rules goes without saying, but that is not "the Ch. m."!

Enough, it goes on like this: mistake after mistake. I don't understand how a careful person can write a book like this ‒ and not revise it in due course.

No comments:

Post a Comment