There is nothing wrong, with having found one's field.

Everything is wrong when one finds the same mistakes from the first article to the last.

In my view, the last one (Seeing and Hearing the Book: A Moroccan Edition of the Qurʾan) is just a string of errors, not worth listing them.

In it she compares "the Saudi edition" with "the Moroccan Qur'an" aka "the muṣḥaf muḥammadī" although there are more than a hundred Saudi editions, more than hundred Moroccan Qur'an editions and three very different "Muṣḥaf Muḥammadī" (about ten with minor differences).

The "differences between THE Saudi and THE Morroccan" do not exist:

Moroccan editions are the transmission of Warš following Nafīʿ, with saǧadā signs according to the Malikī maḏhab, Madinī verse counting, Maġribī handwriting/font.

What Cohen shows as THE Saudi edition is the transmission of Ḥafṣ following ʿĀṣim, with saġadā signs according to the Hambalī maḏhab, Kūfī counting, nasḫī handwriting/font by ʿUṯmān Ṭaha, printed by KFC.

But there are Moroccan reprints of Saudi editions ... ... and the Suʿudī "King Fahd Glorious Quran Printing Complex" (KFC) publishes the Warš transmission in Maġribī handwriting.

Suʿudī is not always the same. The KFC publishes editions for North-West Africa and for India (but not for Turkey, Iran, nor Indonesia).

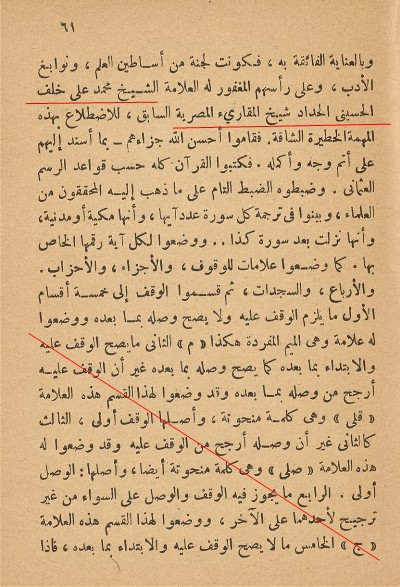

Here images that show that there is no clear cit between muṣḥaf muḥammadī"-Malikī and the rest-non-Maliki According to Cohen this is THE muṣḥaf muḥammadī fatiḥa: But this is a muṣḥaf muḥammadī fatiḥa as well: According to Cohen this is THE Saudi one But these are two more (out of many) from Madina To put it bluntly. What Cohen writes is based on 90% ignorance resp. blindness.

p.142: "According to the protocol defined in the 1920s in Cairo by al-Azhar each stage of prouction should be subject to control."

‒ no source given, definetly wrong

p.144: "the Egyptian copy [of the Qurʾān] developed at al-Azhar in 1924

‒ just wrong

p.144: "Contrary to the muṣḥaf ḥassanī, which was to be offered to distinguished guests, the muṣḥaf muḥammadī was placed under serial and industrial production."

‒ wrong, both maṣāḥif have expensive (big, colour, glossy paper) versions and cheaper ones, and none is gift only: one could buy them. Before I move on to the Warš muṣḥaf of 1929: A.Cohen writes three pp. 145-148 on the calligraphy of the "Moroccan muṣḥaf" incl. strange things like "'The line should not be so long, even if it does not change the meaning. There should be no excessive reading.'” quoting a "cleric". ‒ first, the cleric says: "There should be no extended line because that could lead to prolongation in reciting." ‒ second, "of course" there are extended lines in Maġribī maṣāḥif to justify lines. The first word /ḏālika/ is from Cohen's text, showing what is forbidden. All others are from Muṣḥaf al-Ḥasanī. Three pages, but she does not mention THE most important fact:

Let's move to what she calls "the 'Qurʾan of Zwiten,'26 26 ... Until recently, the rights to it belonged to Dar al-muṣḥaf al-sharīf, in Cairo. See Abdulrazak Fawzi, The Kingdom of the Book: The History of Printing as an Agency of Change in Morocco between 1865 and 1912 (PhD diss., University of Boston, 1990)."

Of course A. Fawzi says nothing of the kind. Why else do we not get a page number, where he would say so? A.Cohen is making it up as in most of her publications: Hot air or lies!

Of course we do not get any information about this print of reference, not even a picture of the cover, nor of any of the pages! ‒ just as in her earlier articles she wrote that it was very often reprinted without giving years, nor publishers!

As often, Bergsträßer tells us a lot

She does not know that most Western readers need the number of suras.

"al-Naml (the Ants)" should be "XXVII" or "an-Naml (27)".

ḫaṭṭ is handwriting, script, not calligraphy which is fann al-ḫaṭṭ.

taḏhīb is gilding, not illuminations.

taškīl is vocalization, not "vocalization signs"; vowel signs are harakāt.

the commander of the believers, not commanders of believers:

Why does she call his function "myth"?

She translates her French "encore" (in Voir et entendre le Livre. Une édition marocaine du Coran. 2017) (which means here « en outre »/"furthermore, moreover") as "still"/ « toujours » « quand même » .

The article feels like written by a large language model artificial intelligence.

Some sentences sound reasonable, others like halucinations

Sometimes the connection is missing: first [he writes] "on paper plates",

which are then "calligraphic tablets".

lawḥ, a wooden tablet, is defined as "a Qurʾanic tablet that combines writing and recitation"

‒ it has no loud speakers.

First she writes ‒ correctly ‒ of "the seven canonical readings (qirāʾa)",

then ‒ incorrectly ‒ of "the seven Moroccan recitations";

the seven qirāʾāt (proper plural form) neither being Moroccan, nor recitations.

similarly: "the dominant recitation in Morocco (Warsh)" ‒ the ways of recitation (taḥzzabt, muǧawwd, murattal) have nothing special to do with Warš ‒ no more than "high way" with Chrysler and Tesla.

her note 2: muṣḥaf = volume, Qurʾān = revelation, while the first is "codex", the second "reading, recitation"

In note 20 she cites Gérard Troupeau with: "To indicate the three short vowels, [Arabic] borrowed three Syriac signs" although Troupeau has not written this, and it is certainly wrong.

The most common edition is in the "Unified Maghribi script" al-ḫaṭṭ maġribī at-tūnisī al-ǧazāʾirī al-ifrīqī al-muwaḥḥad ‒