Gabriel Said Reynolds and others say that all Qur'anic texts are identical: letter for letter.

the various editions of the Qur'an printed today (with only extra-ordinary exceptions) are identical, word for word, letter for letter.

"Introduction to The Qur'an in its Historical Context, Abingdon: Routledge 2008, p.1.

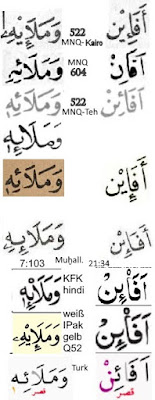

Nonsense! There are probably a thousand different ways of writing or typesetting Qurans.

That does not mean that the prints say different things. They don't. They are similar enough -> mean the same.

The differences that the exact same text allows in interpretation are certainly 100 times more significant than all the differences between different prints. Many differences are purely orthographic (such as folxheršaft and Volksherrschaft, night and nite, le roi and le rwa), others change the sense of a word, even a sentence, but do not really change the passage.

I am not at all concerned with contradictions in the Qur'an, with differences in content between one and another, I am only concerned with differences in orthography (that is, the spelling rules and particular cases).

Nor am I concerned with the differences between the seven/ten canonical readers, the fourteen/ twenty transmitters, the hundreds of tradents. These primarily concern the phonetic structure (sometimes a "min" or "wa", an alif or a consonant doubling more or less); the variants only say whether a vowel is lengthened fivefold or threefold, whether the basmala is repeated between two suras or a takbir is spoken before a particular one. I am not concerned with all this.

I am interested in the differences between Ottoman and Moroccan, Persian and Indian

maṣāḥif ‒ and how the official Egyptian Qurʾān of 1924 differs from those before it. Because there is a lot of nonsense circulating about this.

Qurans differ in a hundred ways. I will not present this systematically. For example, reading style, writing style, lines per page, whether verses may be spread over two pages, whether 30th must begin on a new page, whether

rukuʿat are displayed in the text and on the margin, whether verses have numbers and whether pages have custodians/catch words on the bottom of each (second) page, whether there are one, three, four, five, six ... or sixteen pause signs. All this can occur, but will not be systematically discussed.

I focus attention on two points:

the spelling of words, the Quranic vocabulary, so to speak ‒ although (unlike

Le Dictionaire de l'Academie, Meriam-Webster, Duden) the same word is not to be written the same way in all places;

the rules of how vowel length, shortening and diphtongs are notated, like assimilation of consonants.

I am particularly interested in prints.

There are two main spellings/set of rules: African (Maghrebi, Andalusian, Arabic) and Asian (Indo-Pakistani, Indonesian, Persian, Ottoman): Africans always need two signs for long vowels: a vowel sign and a matching elongating vowel letter; if the latter is not in the

rasm, it is added in small (or a non-matching one is made suitable by a Changing-Alif).

Asians have three short vowel signs and three long vowel signs (plus

Sukūn/Ǧazm). But according to today's IPak rules, for ū and ī, one uses the short vowel signs IF the matching vowel letter follows (which gets a

ǧazm). With long ā, Persians and Ottomans/Turks always used the long vowel sign; Indians today use it only if no

alif follows (i.e.

wau, [dotless]

yāʾ or no vowel at all); if an

alif follows, the consonant before it only gets a

Fatḥa. In the case of long-ī, Persians and Ottomans always used the Lang-ī sign (regardless of whether it is followed by yāʾ or not); Indians today proceed similarly to ā: if it is not followed by a

yāʾ, the long-ī sign is used: before

yāʾ, however, there is (only)

Kasra and the

yāʾ gets a

ǧazm. (According to IPak, sign-less letters are silent!).

For long ū, Ottomans put

"madd" under a wau; for the elongated personal pronoun

-hū the elongation remains unnotated.

Indians and Indonesians use the long ū sign but the short u sign before wau,

while before 1800, Indians always used the long-ū-sign, following wau remained without any sign was thus silent (to be ignored when reading) ‒ if it is second part of the diphtong au, it got and gets a

Ǧazm, thus is to be spoken. Always the long ī sign. Always the long-ā-sign. In other words:

In 1800, there were two systems of noting

long vowels: the Maghrebian, which always included two parts, a vowel sign

(fatḥa, kasra, ḍamma, imāla-point) and a lengthening vowel (belonging to the

rasm or a small complement). And an Indian system based entirely on long vowel signs, in which the vowel letters present in the

rasm were completely ignored. The Maghrebi system is used today in Africa and Arabia. The Indian system is used in weakened forms in Turkey, Persia, India and Indonesia. In India and Indonesia, IPak applies, where long ā continues to be used before (dotless)

yāʾ, but before alif it has been replaced by

fatḥa (like in the African system) Before ī-

yāʾ / ū

-waw stand

kasra / ḍamma; abobve the vowel letter stands

ǧazm ‒ otherwise they had no influence on pronounciation. The old Indian system only applies where no vowel letter follows.

How widespread this clear Indian system was, I do not know. I came across several manuscripts using it, but no print.

No trace of the word in question.

What we do find in the verse before looks very different from what van Putten calls "Cairo"

No trace of the word in question.

What we do find in the verse before looks very different from what van Putten calls "Cairo"

Please call it "Basic Quranic Text" "rasm plus" or anything of the sort.

"Cairo" short for "Gizeh 1924" is not a sceleton, it is a masoretic text!

a bundle of features that make a muṣḥaf!

I am sure you have no idea what "Gizeh 1924" aka "King Fu'ad" is.

You could have taken ANY muṣḥaf in the WORLD (except Turkey and Persia!)!

Please call it "Basic Quranic Text" "rasm plus" or anything of the sort.

"Cairo" short for "Gizeh 1924" is not a sceleton, it is a masoretic text!

a bundle of features that make a muṣḥaf!

I am sure you have no idea what "Gizeh 1924" aka "King Fu'ad" is.

You could have taken ANY muṣḥaf in the WORLD (except Turkey and Persia!)!

They all have the same Basic Quranic Text, and that's all that you are interested in here.

So please, stop calling "it" "Cairo"!

They all have the same Basic Quranic Text, and that's all that you are interested in here.

So please, stop calling "it" "Cairo"!