Sunday, 22 September 2019

Qurʾānic Orthography

And that they are written alright.

The opposite is true:

there are many different qurʾanic "ortho"graphies and none is ortho/right.

b, k, l, m, n, t ... are fine. Paleo-Linguists argue about ض ص ط ظ

But for modern readers only the vowels are problematic: short and long vowels.

Basically there are two systems:

an Indian system with seven vowel signs (a ā i ī u ū x)

an African System which needs for each long vowel a vowel sign plus the corresponding lengthening letter.

The African system is today common in the Arab world. When there is no lengthening letter (waw, yāʾ, alif) after ḍamma, kasra, fatḥa in the rasm, a small letter is added. When the rules of prosody require an "ī" although no yāʾ is in the rasm, a small yāʾ barī (i.e with the tail to the front) is added.

But when the rules of prosody require a (written/long) yāʾ to be shortened,

that is not reflected in the text.

I am shocked because the lengthening of vowels required by prosody IS shown.

I had no problem with sticking to the base letters, but adding reading helps sometimes defies God's logic.

(Turks and Persians do never show the niceties of quranic assimilation. ‒ That I can understand.)

(Turks note lengthened ī, but not lengthened ū ‒ something corrected in all Indonesian and some Iranian reprints.)

Indians, Turks, Persians, Indonesians are not happy with this. The Arab attitude "everybody knows that these letters do not lengthen the vowel at these places" sounds arrogant in non-Arab hears.

In XXX:10 /ʾasāʾŭ s-sūʾā/ in India (second line) and Indonesia (last, right) there is no vowell sign about the wau in /ʾasāʾŭ/, hence it is not pronounced (just as the following alif).

In Kerala (first, right) and Turkey (fourth line) that wau is silent because it is only the "seat" of hamza (there would be written "madd" underneath if it were to be pronounced).

In the new Iranian orthography (fifth line, right) all silent letter are pink.

But in the third line (right: Madina: ʿUṯmān Ṭaha; left: Damascus: Dār al-Maʿrifa) there is no Silent-Sign above the wau.

The same in the last line, left (Tunis: Nous-mêmes) ‒ wrong as I see it.

But two of the taǧwīd-Editions based on UT do show the silence of that wau: On the top, left from Bairut (blueish for silence), on the fifth line, left from Damascus (grey triange above for silence).

When shortening doesn't follow a general rule, but applies just to particular places within the text = when a vowel is short because it must rhyme with lines before and after, this IS reflected in the Arab-African text. So why not: all the time?

Here you see words from an Indian manuscript (from Surat Hūd) in which ONLY the vowel SIGNS count, the "lengthening" vowel letters are IGNORED (hence: NO sign above or below) ‒ al-farīqaini in the last line has jazm above the yāʾ because in the diphthong yāʾ is NOT silent.

((Added later: I first had seen just one manuscript from around 1800 with the sign-only orthography, by now I have seen some more ‒ up to the time when lithographs became common, lithographs with the modern/ mixed way of writing long vowel letters)

on the margin I added doctored versions: signs were moved to a place easier to read for the modern reader

The modern Indian system (black on white background) is a mix of the old consistent system and the African one: when the CORRESPONDING letter follows a vowel sign, the SHORT vowel sign is used (as in Africa), only when there is a different letter or no "lengthening" letter at all, the long vowel sign is used.

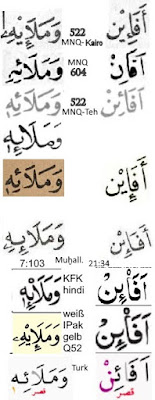

In 7:103, 10:75, 11:97 and 43:46 (and 10:83 with an added mīm for plural) pronounciation and rasm are the same; there is only disagreement on whether the alif or the yāʾ is mute:

wa-malaʾihī

IPak: وَمَلَا۠ئِهٖ

Q52: وَمَلَإِي۠هِۦ

In the rasm there are matres (ḥurūf al-madd) for both /a/ and /i/,

‒ indeed here letters (not consonants!) stand for short vowels,

because there was no other way to notice them.

in India alif is silent (the short fatḥa is valid, not the alif), yāʾ carries hamza,

in Arabia alif "carries" hamza below, yāʾ is silent.

In 21:34 ʾa-faʾin

IPak: افَا۠ئِنْ

Q52: اَفإي۠ن

India and osm/Tur make the alif silent

(Indians used to leave the alif without any sign, now they put the silent making circle,

Turks write qaṣr underneath)

for Arabs alif carries hamza, yāʾ is silent.

Muṣṭafā Naẓīf in one of his manuscripts (the 604 pages berkenar one) just drops the otiose letter. اَفَإنْ

It does not help to observe that in his other maṣāḥif he has the superfluous letter. The 604 page muṣḥaf is often reprinted (not as often as the 522 page one, but in different countries) without "correction".

Similar 6:24 min-nabaʾi In Q52 alif "carries" hamza and /i/, yāʾ is silent and in IPak alif is silent, yāʾ carries hamza and /i/.

Sunday, 8 September 2019

forward to the Middle Ages (the Dark Age)

So the earth was created some five thousand years ago in six days -- including plants, birds, fish, animals, and snakes -- and Adam & Eve.

And in Jerusalem, there was first The First Temple and then The Second Temple.

After the advent of Modernity, scholars made observations, experiments, and excavations.

And no traces of a central temple for the people of Israel was found in Jerusalem, and what is more: There was no United Kingdom.

IF there were David and Salomon, they were petty chieftains.

Of course, if you are looking for a map of the Garden of Eden in the Hebrew Bible, you can believe the existence of the First Temple.

Or you can read the books of Israel Finkelstein (and Neil Asher Silberman) and know what can be known.

Even if there are no traces, one can assume that there was a local temple in Jerusalem and that it was destroyed by Pharaoh Šošeq's army.

The Judean King Jehoaš had a second temple built after 835.

Destroyed around 700 BCE by the Assyrian King Sîn-aḫḫe-eriba.

The third temple was destroyed 597 by the Babylonians, and 586 annihilated.

The fourth ‒ the first of regional importance, but still not THE only temple for יהוה ‒ was built by Zerubbabel and Joshua 520 BCE

or 445 by Nehemiah and Ezra (or was that the fifth?

500 years later Herod the Great built the Sixth Temple.

Around it, he had erected an artificial mount supported by huge stones blocks.

To call this temple the Second is like saying that Pei erected the Louvre and Forster the Reichstag.

And to speak of "Solomon's Temple" is like saying King Arthur defended the UK.

If you say: But the Jews ... I call to your attention that the national socialist Ben Gurion proclaimed the Third Reich (בית השלישי) after "his" army had conquered the Sinai Peninsula.

CC (in the "the World of the Quran" module) talks of Salomon's Temple, showing that they just reproduce what others say, reproducing phrases used by Believers in the Hebrew Bible, showing that they live in the Middle Ages, are not "Wissenschaftler".

To say "around the turn of the eras", "in the third century before ..." is better than "in the so-called Second Temple Period", but it is okay. To calls Herod's temple "The Second Temple" is wrong -- and whoever does it is stupid.

Wednesday, 19 June 2019

Cairo1924 Standard Text Cairo

No trace of the word in question.

What we do find in the verse before looks very different from what van Putten calls "Cairo"

No trace of the word in question.

What we do find in the verse before looks very different from what van Putten calls "Cairo"

Please call it "Basic Quranic Text" "rasm plus" or anything of the sort.

"Cairo" short for "Gizeh 1924" is not a sceleton, it is a masoretic text!

a bundle of features that make a muṣḥaf!

I am sure you have no idea what "Gizeh 1924" aka "King Fu'ad" is.

You could have taken ANY muṣḥaf in the WORLD (except Turkey and Persia!)!

Please call it "Basic Quranic Text" "rasm plus" or anything of the sort.

"Cairo" short for "Gizeh 1924" is not a sceleton, it is a masoretic text!

a bundle of features that make a muṣḥaf!

I am sure you have no idea what "Gizeh 1924" aka "King Fu'ad" is.

You could have taken ANY muṣḥaf in the WORLD (except Turkey and Persia!)!

They all have the same Basic Quranic Text, and that's all that you are interested in here.

So please, stop calling "it" "Cairo"!

They all have the same Basic Quranic Text, and that's all that you are interested in here.

So please, stop calling "it" "Cairo"!

Tuesday, 18 June 2019

Madd al-Muttasil and Madd al-Munfasil

an Ottoman muṣḥaf (MNQ) with a black madda sign withIN words, red ones at the end of words, when the next words starts with hamza.

and here sniplets from a Persian one (Nairizī):

an Ottoman muṣḥaf (MNQ) with a black madda sign withIN words, red ones at the end of words, when the next words starts with hamza.

and here sniplets from a Persian one (Nairizī):

hier an Indo-Pak muṣḥaf (with different signs):

hier an Indo-Pak muṣḥaf (with different signs):

and an modern Indonesian one:

and an modern Indonesian one:

In the muṣḥaf muʿallim riwāyat Qālūn of Edition Nous-Mêmes in Tunis there are three different madda signs.

In the muṣḥaf muʿallim riwāyat Qālūn of Edition Nous-Mêmes in Tunis there are three different madda signs.The thick one for the "mysterious" letters and within a word (2 madda), the thin/normal one at the end of a word (before hamza) (1 madda):

Note: I am not using the Arab terms -- and warn against them -- because the editors use them differently:

Note: I am not using the Arab terms -- and warn against them -- because the editors use them differently:

note further:

They have a third madda sign: 1 1/2 madda before a pause.

Since some of the pauses are optional, the lengthening is conditional on the actual pause: when the reader chooses not to pause this a "1 madda"

I guess it would be best to encode four madda signs:

the very long one ‒ used only in the East for the "mysterious" letters

the long one ‒ for lengthening within a word (and the"mysterious" letters)

the longer one ‒ (1 1/2 before pause, seldom used)

the normal one ‒ used at the end of words and in MSA.

The "small madda" should not be used in the data stream,

type technology chooses a size according to the letter.

note further:

They have a third madda sign: 1 1/2 madda before a pause.

Since some of the pauses are optional, the lengthening is conditional on the actual pause: when the reader chooses not to pause this a "1 madda"

I guess it would be best to encode four madda signs:

the very long one ‒ used only in the East for the "mysterious" letters

the long one ‒ for lengthening within a word (and the"mysterious" letters)

the longer one ‒ (1 1/2 before pause, seldom used)

the normal one ‒ used at the end of words and in MSA.

The "small madda" should not be used in the data stream,

type technology chooses a size according to the letter.

Saturday, 15 June 2019

@marijn van putten QCT

The QCT is defined as the text reflected in the consonantal skeleton of the Quran, the form in which it was first written down, without the countless additional clarifying vocalisation marks. The concept of the QCT is roughly equivalent to that of the rasm, the … undotted consonantal skeleton of the Quranic text, but there is an important distinction. The concept of QCT ultimately assumes that not only the letter shapes, but also the consonantal values are identical to the Quranic text as we find it today. As such, when ambiguities arise, for example in medial ـثـ ،ـتـ ،ـبـ ،ـنـ ،ـيـ etc., the original value is taken to be identical to the form as it is found in the Quranic reading traditions today. This assumption is not completely unfounded.You are right: the assumption is not completely unfounded, it is logically impossible, ‒ because there is no COMMON CONsonantal text. The "QCT" is not purely consonantal: ‒ there are letters for long vowels and diphtongs, ‒ there are letters for short vowels, the u in ulaika being the most common, but there are others: (26:197; 35:28) اولى , العُلَمَـٰوا۠ نَبَواْ (14:9 = 64:5, 38:21, 38:67) but (9:70) نَبَا Or ساورىكم (7:145, 21:37), لاوصلٮٮكم (7:124, 20:71, 26:49) Look at the 22nd word in 3:195 واودوا six letters, not six consonants, ‒ the alifs after final waw are no consonants but just end-of-word-markers. often اولٮك rarely وملاٮه (7:103 الأعراف١٠٣) وملاٮه ( bei dem man heute zwei stumme Buchstaben sieht: einen hamza-Träger und einen überflüssigen; ursprünglich standen die für (Kurz-)Vokale (a i, aʾi, ayi). Genau so ist es bei اڡاىں (3;144 + 21:34) IPak: افَا۠ئِنْ Q52: اَفإي۠ن In the common اولٮك waw stood for /u/; today it is seen as mute/otiose, because the ḍamma above alif stands for /u/. ‒ because there is no "Quranic text as we find it today" either. There is no rasm al-ʿUṯmānī either, i.e. not a single rasm, there are five or more. There are about 40 differences between the maṣāḥif written at the behest of ʿUṯmān. There must be almost 100 lists of these floating around, inter alia in my book Kein Standard (based on Bergsträßer GdQ3), and on this Turkish site, that is pffline now. The QCT can not be "identical to the Quranic text as we find it today" because there is no "identical Quranic text … found in the Quranic reading traditions today". You seem to believe that the qirāʾāt just differ in "the countless additional clarifying vocalisation marks". That's wrong. There are many books showing the differences between the ten readers, twenty transmitters and more than 50 recognized waysplus three multi-volume encyclopediae for the un-recognized readings. As there are many more differences than in ḥarakāt and tašdīd, and I just have to give some examples, to prove my case, I take them from Adrian Alan Brocketts Ph.D., words differently dotted in Ḥafṣ and Warš: ءَاتَيۡتُكُم ءَاتَيۡتنَٰكُم (3:81) تَعۡمَلُونَ يَعۡمَلُونَ (2:85) تَعۡمَلُونَ يَعۡمَلُونَ (2:140) (3:188) تَحۡسَبَنَّ تَحۡسِبَنَّ (4:73) تَكُن يَكُن (2:259) نُنشِزُهَا نُنشِرُهَا (2:58) يُغۡفَرۡ نَّغۡفِرۡ (2:165) يَرَى تَرَى ترونهم يرونهم (3:13) (3:83) يَبۡغُونَ تَبۡغُونَ يُرۡجَعُونَ تُرۡجَعُونَ(3:83) (3:115)يَفۡعَلُوا تَفۡعَلُوا يُكۡفَرُوهُ تُكۡفَرُوهُ (3:115) يَجۡمَعُونَ تَجۡمَعُونَ (3:157) (2:271) يُكَفِّرُ نُكَفِّر (3:57) فَنُوَفِّيهمُ فَنُوَفِّيهمُۥۤ (4:13) يُدۡخِلۡهُ نُدۡخِلۡهُ (4:152) يُؤۡتِيهِمۡ نُوتِيهِمُۥٓ What is true for the first four suras, is true for the rest. And what is true for these two transmissions, is true for all others. Okay, more than 90% of the words are the same in all transmissions, but that's not good enough to speak of a common consonantal text. It would be nice, when the Sultan of Oman (or someone else), paid Thomas Milo to make one muṣḥaf that represents sixty maṣāhif: ‒ a basic Common Quranic Text CQT with the possibility to make disappear: the vowel letters, and/or the end-of-word-markers, and the possibility to add letters specific to an old muṣḥaf (Kûfā, Baṣra, ) ‒ in a special colour to add diacritical points for transmissions ‒ in an other colour plus ḥarakāt specific to certain transmissions. plus assimilation marks, plus pause signs, plus ihmāl signs. Maybe even with verse numbers according to Kufa, to Ḥims, to Medina II … and one day even following MS. O....xyz ‒ God willing. BTW: The old grammar knows just letters/sounds/particles/ḥurūf,

no con-sonants and sonants.

It makes no sense to call Phoenician, Hebrew, Arabic

letters "consonants."

Only after Greeks used some letters ONLY for sonants/vowels,

the other letters became con-sonants.

As long as these signs function as end-of-word-markers (silent

alif after waw, mem sofit, khaf sofit, many Arab end-letters),

stand for a con-sonants or for a long vowel or for a short vowel

or for a diphtong ‒ as in the qurʾān ‒

there ARE NO "consonants", just letters.

Tuesday, 21 May 2019

experts say ...

| Q52 IPak | Q52 IPak | Q52 IPak | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| There are | leading | middle | trailing | Alifs |

| hamza | ء vsign | ء ء | ء ء | |

| mater lec. | ‒ | X | X | |

| silent | waṣla X | circle X | circle X X X | Alif wiqāya accusative marker |

Here Turks (last line) have the same silent alif; they shorten it, i.e. the fatḥa is valid, the alif is not.

BTW: In one of the three maṣāḥif of Muṣṭafā Naẓīf the yāʾ is missing -> the alif carries the hamza+kasra (first line on the right side).

Here Turks (last line) have the same silent alif; they shorten it, i.e. the fatḥa is valid, the alif is not.

BTW: In one of the three maṣāḥif of Muṣṭafā Naẓīf the yāʾ is missing -> the alif carries the hamza+kasra (first line on the right side).

Here Turks (first line) actually have an otisose alif LESS (END of my snippet)

What these experts want to say:

There are more Alif Matres lectionis, i.e. alifs standing for /a/.

Here Turks (first line) actually have an otisose alif LESS (END of my snippet)

What these experts want to say:

There are more Alif Matres lectionis, i.e. alifs standing for /a/.

millions good editions possible

If you a sceptical and lazy, here is mālik from the Fatiḥa with /ā/ red added alif:

And here the one verse where Ḥafs allows both fatḥa (black) and ḍamma (red): /ḍaffin/, /ḍuffin/

If you a sceptical and lazy, here is mālik from the Fatiḥa with /ā/ red added alif:

And here the one verse where Ḥafs allows both fatḥa (black) and ḍamma (red): /ḍaffin/, /ḍuffin/

And when you think, that for the rasm there are five, six or maybe ten possibilities, you are wrong.

When you write a muṣḥaf (or prepare a printing) you do not have to stick to one authority.

You are free to write one word (even a word at one particular place) with a vowel letter or without.

The King Fahd Complex has adopted the rasm of the Qahira1952 Edition (which is rather obscure) changed one word (in 2:72), Qaṭar has changed another word (in 56:2). Indonesia (Ministry of Religious Affairs) and Iran (the Center for the Printing and Distribution of the Holy Quran) have made wild choices ‒ at least these are documented (albeit not in the muṣḥaf).

BTW, I called Q52 obscure, because it does itself not stick to an authority. Therefore careful editors have added "mostly"/ġāliban or "in the most"/fil ġālib to the statement made in the afterword, that the rasm is according to Ibn Naǧāḥ.

So millions of different ‒ equally valid ‒ editions are possible, thousands do exist.

I am mainly interested in orthography:

i.e. the list of the written words ‒ but unlike Webster or Le Dictionaire de l'Académie Franҫaise a word can be written differently at different places

(سِيمَىٰهُمۡ (7:48

(2:273, 47:40, 55:41) سِيمَـٰهُمۡ

(سِيمَاهُمۡ (48:29

The German expert for Qurʾānic paleo-orthography, who has studied the old mss.

‒ Diem has "just" studied the Nabataen precursor ‒

is convinced that first the yāʾ was used for writing the /ā/,

then nothing, before the modern strategy ‒ using an alif ‒ became common.

I do not give his name because I have to critize him strongly:

Although quoting the text of the Gizeh Qurʾān (1924/Būlāq 1952), which he calls "The Standard Text",

he uses a dotted yāʾ where Gizeh uses an undotted one,

and he uses the circle for sukûn, where Gizeh uses the Indian (by now Qurʾānic) Jazm-sign.

He does not see that graphic style, divisions, rasm writing, and the way of voweling are independent of each each.

what I have shown above.

Or even more to the point:

the differences in sounds (the qiraʾāt) reflected in very few differences in the rasm,

And when you think, that for the rasm there are five, six or maybe ten possibilities, you are wrong.

When you write a muṣḥaf (or prepare a printing) you do not have to stick to one authority.

You are free to write one word (even a word at one particular place) with a vowel letter or without.

The King Fahd Complex has adopted the rasm of the Qahira1952 Edition (which is rather obscure) changed one word (in 2:72), Qaṭar has changed another word (in 56:2). Indonesia (Ministry of Religious Affairs) and Iran (the Center for the Printing and Distribution of the Holy Quran) have made wild choices ‒ at least these are documented (albeit not in the muṣḥaf).

BTW, I called Q52 obscure, because it does itself not stick to an authority. Therefore careful editors have added "mostly"/ġāliban or "in the most"/fil ġālib to the statement made in the afterword, that the rasm is according to Ibn Naǧāḥ.

So millions of different ‒ equally valid ‒ editions are possible, thousands do exist.

I am mainly interested in orthography:

i.e. the list of the written words ‒ but unlike Webster or Le Dictionaire de l'Académie Franҫaise a word can be written differently at different places

(سِيمَىٰهُمۡ (7:48

(2:273, 47:40, 55:41) سِيمَـٰهُمۡ

(سِيمَاهُمۡ (48:29

The German expert for Qurʾānic paleo-orthography, who has studied the old mss.

‒ Diem has "just" studied the Nabataen precursor ‒

is convinced that first the yāʾ was used for writing the /ā/,

then nothing, before the modern strategy ‒ using an alif ‒ became common.

I do not give his name because I have to critize him strongly:

Although quoting the text of the Gizeh Qurʾān (1924/Būlāq 1952), which he calls "The Standard Text",

he uses a dotted yāʾ where Gizeh uses an undotted one,

and he uses the circle for sukûn, where Gizeh uses the Indian (by now Qurʾānic) Jazm-sign.

He does not see that graphic style, divisions, rasm writing, and the way of voweling are independent of each each.

what I have shown above.

Or even more to the point:

the differences in sounds (the qiraʾāt) reflected in very few differences in the rasm,in few cases by different diacritical points, but mainly by hamza sign, šadda and vowel signs and most rasm differences (differences in writing long vowels) are two separate things. Just because the only edition of the transmission of Qālūn according to Nāfiʿ he owns, follows the rasm described by ad-Dānī in the Muqnī, he calls that rasm "the Qālūn rasm", he takes the delivery boy for the pizza backer. Okay, I went too far. Between Kufa (Ḥafṣ and five others) and Medina (Warš and Qālūn) there are 30 differences in the rasm. When you look at the beginning of 46:15 in my pictures, there are two differences: aḥsana(n)

Monday, 13 May 2019

thousand different editions

Perhaps the best known example for the importance of pauses is 3:7 (the seventh verse of surat Āl ʿImrān) Here are almost twenty published English translation of the same (exactly the same!) words: SahihIntern: And no one knows its [true] interpretation except Allah. But those firm in knowledge say, "We believe in it. All [of it] is from our Lord." Muhammad Taqi-ud-Din al-Hilal & Dr Muhammad Muhsin Khani (KFC): but none knows its hidden meanings save Allah. And those who are firmly grounded in knowledge say: "We believe in it; the whole of it (clear and unclear Verses) are from our Lord." Yusuf Ali: but no one knows its hidden meanings except Allah. And those who are firmly grounded in knowledge say: "We believe in the Book; the whole of it is from our Lord:" Pickthall: None knoweth its explanation save Allah. And those who are of sound instruction say: We believe therein; the whole is from our Lord; but none knows their meaning except God; and those who are steeped in knowledge affirm: "We believe in them as all of them are from the Lord." But only those who have wisdom understand. Ali Unal: although none knows its interpretation save God. And those firmly rooted in knowledge say: "We believe in it (in the entirety of its verses, both explicit and allegorical); all is from our Lord"; Aziz Ahmed: but none know the interpretation of it except Allah. And those who are well-grounded in knowledge say, "We believe in it; it is all from our Lord"; Daryabadi: the same whereas none knoweth the interpretation thereof a save Allah. And the firmly grounded in knowledge Say: we believe therein, the whole is from our Lord. Faridul Haque: and only Allah knows its proper interpretation; and those having sound knowledge say, “We believe in it, all of it is from our Lord”; Muh Assad: but none save God knows its final meaning. Hence, those who are deeply rooted in knowledge say: Shabbir Ahmed: None encompasses their final meaning but God. Those who are well-founded in knowledge understand why the allegories have been used and they keep learning from them. They proclaim the belief that the entire Book is from their Lord. Sarvar: No one knows its true interpretations except God and those who have a firm grounding in knowledge say, "We believe in it. All its verses are from our Lord." Ali Shaker: but none knows its interpretation except Allah, and those who are firmly rooted in knowledge say: We believe in it, it is all from our Lord; AbdulMannen: But no one knows its true interpretation except Allâh, and those firmly grounded in knowledge. They say, `We believe in it, it is all (- the basic and decisive verses as well as the allegorical ones) from our Lord.´ Muh. Ali: And none knows its interpretation save Allah, and those firmly rooted in knowledge. They say: We believe in it, it is all from our Lord. Sher Ali: And none knows it except ALLAH and those who are firmly grounded in knowledge; they say, `We believe in it; the whole is from our Lord.' Rashad Khalifa: None knows the true meaning thereof except GOD and those well founded in knowledge.They say, "We believe in this - all of it comes from our Lord." But they are not different because of the English language, but because of a particular pause or absence of a pause; When you make a pause after "Allāh" he alone knows.When there is no pause, he and some humans know. Better known are the different readings, their transmissions and ways/turuq. These can differ in words, but not in meaning: "We created" and "He created" are not the same, but they say the same: God created!. Sometimes the meaning of a verse/aya in one reading differs from the same aya in another, but this never affects the meaning of a paragraph.

Saturday, 16 March 2019

not one, but three, tens, hundreds

the various editions of the Qur’an printed today (with only extra-ordinary exceptions) are identical, word for word, letter for letter."Introduction" to The Qur'ān in its Historical Context, Abingdon: Routledge 2008, p. 1

from left to right: Syrien, Qaṭar, Kuwait (al-Ḥaddād), Bahrain, Saudia, VAE (both UT1), Dubai, Saudia(UT2), Kuwait (UT1), Oman, Kerbala, Ägypten (Abu Qamar)Yes, nowaday most maṣāḥif produced in the Arab mašriq are similar, but Morocco, Libya, Sudan, Turkey, Tartaristan, Brunai, Indonesia follow different rules, and the Indian Standard (Pakistan, Bangla Desh, UK, South Africa, Surinam, Nepal, Ceylon) is numerically more important and quite different. "Nowadays" because before 1980 a Ottoman muṣḥaf written by Ḥafiz ʿUṭmān the Elder (1642‒1698) was prevalent in Syria, and two Ottoman maṣāḥif written by Ḥasan Riḍā and Muḥammad ʾAmīn ar-Rušdī respectively were produced for Dīwān al-Awqāf al-ʿIrāqī (still 1980 the governments of Qaṭar and Saʿūdī ʿArabia had copies printed of the one based on Rušdī ‒ and 1415/1994 in Tehran): It took some seventy years before the 1924 edition (or rather its 1952 offspring) had created a regional standard. Because there are THREE well established standards and a few in Indonesia, a new one in Brunei, several (competing ones) in Iran and many all over Africa ‒ where we do not only find different ways of writing the same reading (Ḥafṣ ʾan ʿĀṣim) but three more transmissions (Warš, Qālūn, ad-Dūrī ʿan Abī ʿAmr). And 100 years ago, maṣāḥif were less standardized. There are many more printed in Damascus (or Bairūt because of the war), produced in ʿAmman and the UAE and published on the world wide web, but these are mainly for study, not for devotion. But here I will not focus on the readings (and their transmissions), but on different orthographies (of the transmission Ḥafṣ ʿan ʿĀṣim). Already 35 years ago Adrian Alan Brockett found out that the 1342/1924 King-Fuʾād-Edition had not established THE standard, that even the successor of al-Ḥusainī al-Ḥaddād as the chief reciter of Egypt ‒ hence main editor of the "second edition" of 1952 ‒ ʿAlī Muḥammad aḍ-Ḍabbāʿ (1304/1886-1380/1960), had edited different editions and approved of yet more dissimilar ones. Brockett studied editions at a time when only Ḥafṣ and Warš were printed. Today one finds many editions of Qālūn, some of Dūrī and both printed ones and just pdfs for most of the others, plus many editions about the 20 canonical transmissions, plus sound files of recitations of most transmissions. When Brockett wrote, the King Fahd Complex had not started to publish different variants ‒ Ḥafṣ, Šuʿba, Warš, Qālūn, Dūrī, as-Sūsī written by ʿUṭmān Ṭāhā plus an Indian Ḥafṣ ‒ but he had noticed that Gulf States published a) in the new Egyptian style, b) an Ottoman muṣḥaf (the muṣḥaf of Muḥammad ʾAmīn ar-Rušdī with minor modifications), c) in the Indian style. 1952: Brockett's thesis is still the best English "book" available on differences between copies of the qurʾān, although it was researched before the internet facilitated research, before Unicode made it easier to reproduce Arabic script, before it was easy to get hold of all the canonical transmissions and most of the thousands of variant readings (collected in three different editions). His main conclusions ‒ the oral transmission and the one in writing reinforced each other, controlled each other, never were left without the other, and there is no single standard of writing, and no single standard of reciting the qurʾān, and the differences between transmissions (and within transmissions) are minor, they never change the meaning of a paragraph ‒ stand intact. But it was a thesis, no published book. Because the young student was not allowed to have it read by fellow researchers, it is full of mistakes, mistakes which would have been eliminated before publication as a book. I personally have no use for Brockett's "transliteration", which is neither that nor a transcription. I am sure that Brockett ‒ as many readers ‒ did not know what the two terms mean: a transliteration must render the Arabic letters faithfully and must be reversible (not necessarily pronounceable), a transcription must render the sound of the words faithfully, must be pronounceable, should be readable after some instruction, but has not to be reversable, because different sequences of letters can be pronouned (hence transcribed) the same way. I personally, hate his terminology, but at least he defines his ‒ odd ‒ terms at the outset: "graphic" means: part of the rasm, "oral" means: not part of the rasm. I say: utter nonsense! Both the rasm and the later signs (dots, hamza, waṣl, shadda, fatḥa, kasra, ḍamma, signs for imāla, tasḥīl, išmām etc.) are graphical, and have to be pronounced = are oral ‒ but there are some otiose letters, which have to be written in a real transliteration (as in R-G Puin's). "oral only" is closer to what he means, but "in the oldest manuscripts not written, at that time: only recited" is it. Sorry, "oral" is not good enough. I hardly can read his "transcription". Why does "a wavy line" means sometimes "oral", sometimes "lengthened"? Anyhow, here and now, there is no need for Brockett's "transliteration", we have Arabic letters! In spite of my criticism, his thesis is a great work of scholarship ‒ and tremendous work, done before we just googled different editions of the qurʾān. The content of this blog and my German one, you can find as book.

Friday, 15 March 2019

Gizeh 1924 <> Cairo 1952 and after

There are three differences on this page between the 1924 and 1952 edition, typical differences found throughout the muṣḥaf -- there are more than 800 of these -- plus four minor corrections.

To show that the changes did not stop 1952, I have copied two version distributed by the King Fahd Complex into the Amiriya-frame:

first ʿUṭmān Ṭāha 1

There are three differences on this page between the 1924 and 1952 edition, typical differences found throughout the muṣḥaf -- there are more than 800 of these -- plus four minor corrections.

To show that the changes did not stop 1952, I have copied two version distributed by the King Fahd Complex into the Amiriya-frame:

first ʿUṭmān Ṭāha 1 then ʿUṭmān Ṭāha 2

then ʿUṭmān Ṭāha 2 On the next pair there is no sura end, no sura title, but again one changed pause sign and on the very last word the hamza has moved from above to below the line (which is one of the four corrections mentioned in the afterwork to "the second printing").

-- the second page is not from the Amiriya but from a Bairut print, hence the page number is on top of the page and the catch word is missing.

On the next pair there is no sura end, no sura title, but again one changed pause sign and on the very last word the hamza has moved from above to below the line (which is one of the four corrections mentioned in the afterwork to "the second printing").

-- the second page is not from the Amiriya but from a Bairut print, hence the page number is on top of the page and the catch word is missing.

On the last pair there is only one difference: kalimatu (line 5) is written with ta maftuḥa vs. marbuṭa.

On the last pair there is only one difference: kalimatu (line 5) is written with ta maftuḥa vs. marbuṭa.

Tuesday, 12 March 2019

Giza 1342/3 1924/5

‒ is not an Azhar Quran

‒ did not trigger a wave of Quran printings

because there was finally a fixed, authorised text.

‒ did not immediately become the Qur'an accepted by both Sunnis and Shiites ‒ did not contribute significantly to the spread of Ḥafṣ reading;

‒ was not published in 1923 or on 10/7/1924.

But it drove the grotty Flügel edition out of German study rooms,

‒ had an epilogue by named editors (although ... see below), ;

‒ stated its sources (although ... see below),

‒ adopted ‒ except for the Kufic counting,

and the pause signs, which were based on Eastern sources.

‒ the Maghrebi rasm (largely after Abū Dāʾūd Ibn Naġāḥ)

‒ the Maghrebi small substitute vowels for elongation

‒ the Maghrebian baseline hamzae before Alif at the beginning of the word (ءادم instead of اٰدم).

‒ the Maghrebic distinction into three kinds of tanwin (above each other, one after the other, with mīm)

‒ the Maghrebic spelling at the end of the sura, which assumes that the next sura is spoken immediately afterwards (and without basmala): tanwin is modified accordingly.

‒ the Maghrebic absence of nūn quṭni.

‒ the Maghrebic non-spelling of the vowel shortening.

‒ the Maghrebic (wrong) spelling of ʾallāh.

‒ the Maghrebī (and Indian) attraction of the hamza sign by kasra

in G24 the hamza is below the baseline ‒ in the Ottoman Empire (include Egypt) and Iran the hamza stays above the line

‒ noted assimilation like in the Maghreb (an in India, Indonesia):

In both examples the first three lines are Ottoman(Rušdī, Ḥasan Riḍā in ʿIrāqī state editions, Muṣṭafā Naẓīf Qairġalī Cairo 1911), in the middle Giza 1924

bellow Maġribī Warš editions ‒ note that in the older edition the second stem (vertical stroke) of لا is lam+šadda, while in the modern Algerian one, it is the first stroke

A new feature was the differentiation of the Maghrebic sukūn into three signs:

‒ the ǧazm in the form of an ǧīms without a tail and without a dot for vowel-lessness,

‒ the circle for never to be pronounced,

‒ the (oval) zero for "only pronounced if paused".

(while before ‒ as in IPak‒ the absence of any sign signifies "not to be pronounced"). Further, word spacing,

baseline orientation and

exact placement of dots and dashes.

Nor was it the first "inner-Muslim Koran print".

Neuwirth may know a lot about the Koran, but she has no idea about Koran prints,

because since 1830 there have been many, many Koran prints by Muslims.

and Muslims were already heavily involved in the six St. Petersburg prints of 1787-98.

It was not a type print either, but ‒ like all except Venice, Hamburg, Padua, Leipzig, St.Petersburg, Kazan and the earliest Calcutta ‒ planographic printing, albeit no longer with a stone plate but a metal plate. Nor was it the first to claim to reproduce "the rasm al-ʿUṯmānī".

Two title pages of Lucknow prints from 1870 and 1877.

In 1895, a Qur'an appeared in Būlāq in ʿuṯmānī rasm, which perhaps meant "unvocalised". Kitāb Tāj at-tafāsīr li-kalām al-malik al-kabīr taʼlīf Muḥammad ʿUṯmān ibn as-Saiyid Muḥammad Abī Bakr ibn as-Saiyid ʻAbdAllāh al-Mīrġanī al-Maḥǧūb al-Makkī. Wa-bi-hāmišihi al-Qurʼān al-Maǧīd marsūman bi'r-rasm al-ʿUṯmānī.

Except for the sequence IsoHamza+Alif, which was adopted from the Maghreb in 1890 and 1924 (alif+madda was not possible, since madda was already taken for elongation), everything here is already as it was in 1924.

Incidentally, the text of the KFA is not a reconstruction, as claimed by al-Ḥusainī al-Ḥaddād (and believed by Bergsträßer); the text does not follow Abū Dāʾūd Sulaiman Ibn Naǧāḥ al-Andalusī (d. 496/1103) exactly, nor Abu ʿAbdallah Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad al-Ḫarrāz (d. 718/1318), but (except in about 100 places) the common Warš editions.

Also, the adoption of many Moroccan peculiarities (see above), some of which were revised in 1952, plus the dropping of Asian characters ‒ plus the fact that the epilogue is silent on both ‒ is a clear sign that al-Ḥusainī al-Ḥaddād al-Mālikī adapted a Warš edition.

All Egyptian readers/recitors knew the Warš and Qālun readings. As a Malikī, al-Ḥusainī al-Ḥaddād ‒ not to be confused with the scribe Muḥammad Saʿd Ibrāhīm al-Ḥaddād ‒ probably knew Warš editions even better than most.

There was the text, supposedly established in 1924, not only in the Maghreb and in Cairene Warš prints, but also already set in Būlāq in the century before.

Now to the date of publication.

One finds 1919, 1923, 1924 and 1926 in libraries and among scholars.

According to today's library rules, 1924 is valid, because that is what is written in the first printing.

But maybe it was a bit later. It says in the work itself that its printing was completed on 10.7.1924. But that can only mean that the printing of the Qurʾānic text was completed on that day. The dedication to the king, the message about the completion of the printing, can only have been set afterwards; it and the entire epilogue were only printed afterwards, and the work ‒ without a title page, without a prayer at the end ‒ was only bound afterwards ‒ probably again in Būlāq, where it had already been set and mounted ‒ and that was only in 1925, unless ten copies were first bound and then "published", which is not likely.

Or the first run was indeed published in 1924, and only the second run (again in Giza) was stamped:

Monday, 11 March 2019

India 1800 Long vowels

the various editions of the Qur'an printed today (with only extra-ordinary exceptions) are identical, word for word, letter for letter.Nonsense! There are probably a thousand different ways of writing or typesetting Qurans.

"Introduction to The Qur'an in its Historical Context, Abingdon: Routledge 2008, p.1.

That does not mean that the prints say different things. They don't. They are similar enough -> mean the same. The differences that the exact same text allows in interpretation are certainly 100 times more significant than all the differences between different prints. Many differences are purely orthographic (such as folxheršaft and Volksherrschaft, night and nite, le roi and le rwa), others change the sense of a word, even a sentence, but do not really change the passage.

I am not at all concerned with contradictions in the Qur'an, with differences in content between one and another, I am only concerned with differences in orthography (that is, the spelling rules and particular cases).

Nor am I concerned with the differences between the seven/ten canonical readers, the fourteen/ twenty transmitters, the hundreds of tradents. These primarily concern the phonetic structure (sometimes a "min" or "wa", an alif or a consonant doubling more or less); the variants only say whether a vowel is lengthened fivefold or threefold, whether the basmala is repeated between two suras or a takbir is spoken before a particular one. I am not concerned with all this.

I am interested in the differences between Ottoman and Moroccan, Persian and Indian maṣāḥif ‒ and how the official Egyptian Qurʾān of 1924 differs from those before it. Because there is a lot of nonsense circulating about this.

Qurans differ in a hundred ways. I will not present this systematically. For example, reading style, writing style, lines per page, whether verses may be spread over two pages, whether 30th must begin on a new page, whether rukuʿat are displayed in the text and on the margin, whether verses have numbers and whether pages have custodians/catch words on the bottom of each (second) page, whether there are one, three, four, five, six ... or sixteen pause signs. All this can occur, but will not be systematically discussed.

I focus attention on two points:

the spelling of words, the Quranic vocabulary, so to speak ‒ although (unlike Le Dictionaire de l'Academie, Meriam-Webster, Duden) the same word is not to be written the same way in all places;

the rules of how vowel length, shortening and diphtongs are notated, like assimilation of consonants. I am particularly interested in prints.

There are two main spellings/set of rules: African (Maghrebi, Andalusian, Arabic) and Asian (Indo-Pakistani, Indonesian, Persian, Ottoman): Africans always need two signs for long vowels: a vowel sign and a matching elongating vowel letter; if the latter is not in the rasm, it is added in small (or a non-matching one is made suitable by a Changing-Alif).

Asians have three short vowel signs and three long vowel signs (plus Sukūn/Ǧazm). But according to today's IPak rules, for ū and ī, one uses the short vowel signs IF the matching vowel letter follows (which gets a ǧazm). With long ā, Persians and Ottomans/Turks always used the long vowel sign; Indians today use it only if no alif follows (i.e. wau, [dotless] yāʾ or no vowel at all); if an alif follows, the consonant before it only gets a Fatḥa. In the case of long-ī, Persians and Ottomans always used the Lang-ī sign (regardless of whether it is followed by yāʾ or not); Indians today proceed similarly to ā: if it is not followed by a yāʾ, the long-ī sign is used: before yāʾ, however, there is (only) Kasra and the yāʾ gets a ǧazm. (According to IPak, sign-less letters are silent!).

For long ū, Ottomans put "madd" under a wau; for the elongated personal pronoun -hū the elongation remains unnotated. Indians and Indonesians use the long ū sign but the short u sign before wau, while before 1800, Indians always used the long-ū-sign, following wau remained without any sign was thus silent (to be ignored when reading) ‒ if it is second part of the diphtong au, it got and gets a Ǧazm, thus is to be spoken. Always the long ī sign. Always the long-ā-sign. In other words:

In 1800, there were two systems of noting long vowels: the Maghrebian, which always included two parts, a vowel sign (fatḥa, kasra, ḍamma, imāla-point) and a lengthening vowel (belonging to the rasm or a small complement). And an Indian system based entirely on long vowel signs, in which the vowel letters present in the rasm were completely ignored. The Maghrebi system is used today in Africa and Arabia. The Indian system is used in weakened forms in Turkey, Persia, India and Indonesia. In India and Indonesia, IPak applies, where long ā continues to be used before (dotless) yāʾ, but before alif it has been replaced by fatḥa (like in the African system) Before ī-yāʾ / ū-waw stand kasra / ḍamma; abobve the vowel letter stands ǧazm ‒ otherwise they had no influence on pronounciation. The old Indian system only applies where no vowel letter follows. How widespread this clear Indian system was, I do not know. I came across several manuscripts using it, but no print.

Nairīzī

Mirza Aḥmad an-Nairīzī (ca. 1650–1747) is the last of the classical Iranian calligraher s. Informations are hard to find, because often und...

-

There are several types of madd sign in the Qurʾān, in South Asian masāhif: madd al-muttasil for a longer lengthening of the vowel used...

-

40 years ago Adrian Alan Brockett submitted his Ph.D. to the University of St.Andrews: Studies in Two Transmissions of the Qurʾān . Now...

-

Although it is often written that the King Fuʾād Edition fixed a somehow unclear text, and established the reading of Ḥafṣ according to ʿĀ...