Strange that the experts write again and again of THE King Fuʾād Edition,

although there are many, different ones ‒ different not only in size and binding, but in content.

The first one ‒ lets called it KFE I was printed in Giza because only the Egyptian Survey could make offset prints ‒ they had experience in the technique because they produced colour maps.

The second one ‒ KFE Ib ‒ was produced in Būlāq, since the Government Press had aquired

offset presses.

The second one ‒ KFE Ib ‒ was produced in Būlāq, since the Government Press had aquired

offset presses.Like KFE I ... ... kfe Ib was stamped after binding because the year of publication giving in the book could not be met, so a stamp indicating the next year was put on the bound copy.

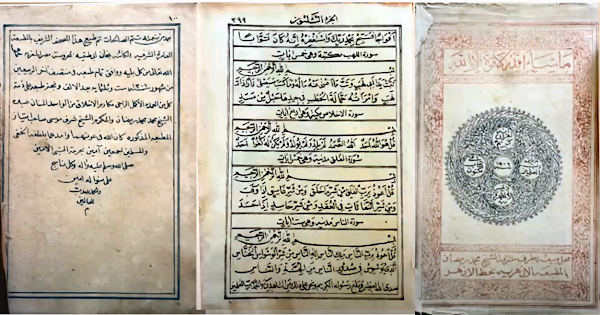

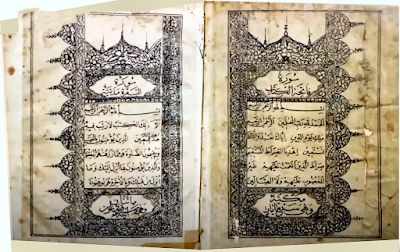

There are changes on two pages ‒ both times: right the Giza print, left the first Būlāq print:

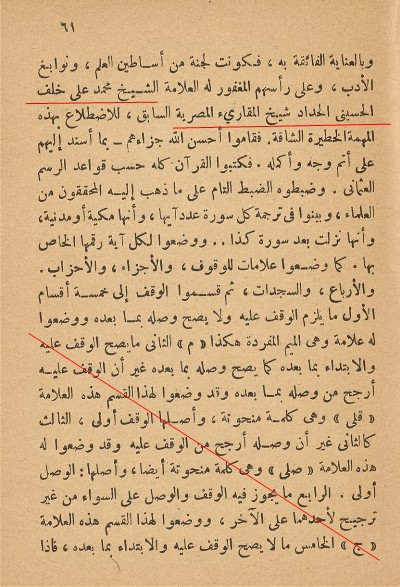

At least as important as seals/stamps instead of signatures is an added word. Because there were no gaps between sorts as was typical in Būlāq prints, readers had assumed handwritten pages. The word "model" made clear that al-Ḥusainī al-Ḥaddād al-Mālikī had "only" written a copy for the type setters.

In the third edition ‒ kfe Ic ‒ one more page was changed: the first page afer the qurʾānic text: In the fourth edition ‒ kfe Id ‒ one more page was changed, the only change IN the qurʾānic text before 1952 (in the first line a (silent) nūn was added): Sorry, here the Gizeh print is on the left. Note, that the the second edition, printed in Bulaq is smaller, but largely due to smaller margins. After 1952, for many years there will be two editions: ‒ a bigger one with seven pages on differences between the edition of 1924/5 and the present one (starting 1952) and with all these changes (almost a thousand) being implemented ‒ a smaller one without this information ‒ and with only a small part of the changes made (on the plate of kfe Ib) . Note that the fourth edition is not printed in Gīza (as the fist), not in Būlāq (as the second), but "in Miṣr" ‒ later yet it will be "in al-Qāhira". Let's resume:

all KFEs were Amīriyya editions,

the first one was printed 1924 in Giza

from 1925 to 1972 they were printed in Būlāq but a 1961 print was made in Darb al-Gamāmīz whether by a private printer or a second factory of the press, I do not know, from 1972 to 1975 print was in Imbāba. All KFEs have 827 pages of qurʾānic text with 12 lines

+ 24 (or 22) paginated backmatter pages + four unpaginated pages for the tables of content.

(until 1952: 24 pages, after the revolution: without the leaf mentioning King Fuʾād)

None of the KFEs has a title page;

they are all hardcover and octavo size (20x28 cm the big one, 17x22 cm the small one ‒ the difference is more in the margin than in the text itself)

All KFE-like editions by commercial Egyptian presses and forgein editions (except the Frommann edition) do have title pages, most of them have one continuous pagination.

There was one miniature reprint of KFE I and at least two private editions + the 1955 Peking reprint; of KFE II there were many re-editions, many rearranged with 14 or 15 (often longer) lines ‒ in many sizes, on thinner paper and with different covers ‒ from Bairut to Taschkent.

In Egypt all the time, editions with 522, 525 (later 604) pages of qurʾānic text were more popular.

For the 15 lines, 525 page, type set Amīriyya print (Muṣḥaf al-Azhar aš-Šarīf) follow the link.

The changes of the second, third and fourth edition did not survive the big change of 1952, which had about 900 changes, but reverted in things just mentioned ("dedication", aṣl, extra nūn in allan) to the first print.

Many private and foreign reprints (and later ʿUṯmān Ṭaha) keep the silent nūn.