Some say: there are only two spellings of the qurʾān:

one on the tablet in heaven, in the ʿUṯmānic maṣāḥif and in the Medina al-Munawwara Edition (or similar to it)

and the other ‒ false ‒ ones.

They say: Both the oral and the graphic form are revealed.

Muhammad instructed his scribes how to write each word.

Polemically phrased: God vouches for the Saʿūdī muṣḥaf calligraphed by ʿUṯmān Ṭaha.

Other think: the qurʾān was revealed orally,

that God vouches only for its spoken shape,

that the written form was fixed by agreement, that it is a convention,

that there are seven ways of writing the qurʾān.

To avoid misunderstandings: Here I do not talk about the different readings,

the different sound shapes, but about ways of writing the same reading,

the rasm and the small signs around it.

First, there is اللوح المحفوظ

in heaven.

We do not know how it looks like.

(2) Then, there are the copies written at ʿUṯmān's time and sent to Baṣra, Kāfā, aš-Šām ...

Again, we do not know how they were spelt, but very old manuscripts give us an impression what they must have looked like. see

(3) Later Arabic orthography underwent change.

We have reports from the third century about the proper writing of the qurʾān.

Although the spelling reported definitely is not the same as (2), it is called "ar-rasm al-ʿUṯmānī";

the Maġrib, India (for some time) and the Arab Countries (since the 1980s) write

their maṣāḥif based on it (with small variants of the rasm, different ways of writing long vowels, different additional sign for assimilation and other fine points).

(4) In countries between the Maġrib and India (Iran, Irāq, Egypt, at some time the Ottoman and Safavid empires) the spelling

came closer to the standard spelling of Arabic ‒ never approaching it, always being different from the "normal", everyday spelling.

This writing is called plene or imlāʾi إملاء .

Turkey has fixed a standard based on the Ottoman practice, Iran is experimenting.

(5) The spelling in different colours, be it to differentiate between the "Uthmanic rasm" and the additions,

be it to show unpronounced letter, lengthened, nasalised, assimilated ones (and so on).

(6) Braille for the blind.

(7) The full (imlāʾī) spelling. In the 1980s, when many of the signs of the 1924 muṣḥaf or the Indian ones were not encoded yet

some signs necessary for Maġribī maṣāḥif are still awaiting inclusion in the fonts ‒

I downloaded such a text called muṣḥaf al-ḥuffāẓ to be used for pronouncing the text,

not to be transferred into a bound volume.

I marked words spelled not according to "ar-rasm al-ʿUṯmānī" in grey.

In Egypt and in Saʿudia rulings have been published

forbidden the writing of the qurʿān like any Arabic text.

They based their view on Mālik ibn ʿAnas, Aḥmad ibn Hambal, and the Šafiʿī al-Baihaqī.

Prominent among their critics is Grand Ayatollah Nāṣr Makārem Širāzī ناصر مکارم شیرازی, born 25 February 1927:

‒ the qurʾān was revealed orally,

‒ the prophet did not fix its written form,

‒ manuscript evidence shows clearly that the "ʿuṭmānic rasm" is not the ʿuṭmānic rasm.

‒ As long as we do not know the ʿuṭmānic rasm, we are free to write, as seems appropriate to us.

‒ Even if we know it one day, we are not bound by it: it is sanctioned "only" by iǧmāʾ ṣaḥāba.

‒ The ʿUṯmān Taha way of writing is not forbidden, BUT is it the best?

‒ There are otiose letters in it, missing letters, connected words, that are normally not connected, words written differently at different places within the muṣḥaf,

it is difficult to read = there are better ways to write it.

On the one hand, Ayatollah Makārem Širāzī points to many differences

between maṣāḥif that claim to follow the ʿuthmanic rasm,

which invalidates their claim,

on the other hand, he does not ask for a radical modern (normal) spelling,

seems to be content with a mix of modern (simpler to read) and archaic spelling,

aiming at proper pronunciation and at correct understanding,

at ease of reading and respect of tradition

(bismillāh, raḥmān ... should be written traditionally,

although their spelling is wrong).

Makārem Širāzī is not alone in attacking "ʿUṯmān Ṭaha's way of writing the qur'ān",

by which they mean to say "the Saʿūdī muṣḥaf and its copies", what Marijn van Putten calls "the Cairo edition" (if I understand him correctely, which is not certain). Ayatollahs

Ǧaʿfar Sobḥānī, Javādī Amol

and Ṣāfī have published similar opinions.

An edition is "one of a series of printings," "the entire number of copies of a publication issued at one time or from a single set of type." Novels normally have a hardcover and a softcover edition. Scholarly books mostly a first, a second and third revised edition, because at the same time and from the same set of type both hardcover and (same or reduced size) softcover are printed.

van Putten writes again and again of "the Cairo edition" and claims that that is a common term for something. But he never defines what he thinks it is.

Is it the 1924 Gizeh edition, the King Fuʾād Edition, the official Egyptian edition of 1924, the 12 liner مصحف 12 سطر, the Survey Authority edition?

Or that he means all editions that roughly have the same text?

He seems not to know, that Gizeh1924 had not a single reimpression (German: Nachdruck, which is different from "reprint");

in Egypt itself, there were only improved editions, already in 1925 there were changes (in the afterword), a completely new set of plates were used, the margins were just about a third of the 1924 edition.

The only edition that had almost the same text is the 1955 Peking edition, but it has one leaf less and all ornamental elements (frame, signs on the margin, title boxes) are different, the headers are different, and it has a title page, which is lacking in Gizeh and Cairo.

The 30st edition or so, named "second print" differs from the 1924 edition at about 900 places.

I fear that van Putten means by "the Cairo edition" all Ḥafṣ editions written by ʿUṯmān Ṭaha, although the King Fahd Complex has further changed the 1952 Amiriyya Edition (2:72, 73:20 and لا pause signs).

What he means by "edition" is not properly called "edition."

but the rasm, the dots and the set of masora of the 1952 edition ‒ ignoring small variants, and ignoring many characteristics of maṣāḥif: lines per page, pages per ǧuz, header, sura title box, margin signs, notes, catchwords and so on.

Although reading, style of writing (can be different for sura name, the basmala, the marginal notes and the text proper), rasm (& dotting), the masora often go together, they are independent of each other: the reading transmission Qālūn can have al-Ḫarrāz, Ibn Naǧāh or ad-Dānī rasm or a mix of them, can be written in Eastern Nasḫi, in Maġribī or a mix thereof, can be on 604 or 60 pages or something in between, can have the Eastern lām-alif or the Western alif-lām!

‒

Thursday, 26 December 2019

Monday, 23 December 2019

the Cairo Committee ‒ ha ha ha

Some time ago I started a blog against the German Orientalist myth of the King Fuʾād Edition as The Standard: Kein Standard. I had no idea that there are scholars outside Germany too, who ascribe this and that to this edition.

Let me admit that the edition printed 1924 in Giza, bound and blind-stamped in Būlāq "ṭabʿat al-ḥukūma al-miṣrīya sanat 1343 hijrīya" (1924/5), without a title on the cover, the spine, without a title page, is important, but not as important as many think and not for the reasons given.

طبعة الحكومية المصرّية

-- . --

١٣٤٣ هجرّية

سـنة

The edition is not and never was The Standard, it has not spread Ḥafṣ ʿan ʿĀṣim (BTW it is not an "Azhar Edition," and no "King Farūq edition" was published in 1936 or anytime). It was not the first that proclaims to follow the ʿUṯmānic rasm, and it is not type printed ‒ it is typeset, offset printed (planographic printing just as lithography). It is not the first with a postscript (Lucknow copies from the 1870s onward and the Muḫallalātī Cairo 1890 print have postscripts ‒ although the latter is sometimes bound as preface ‒ the numbers on the gatherings {malāzim, sg.: mulzama} show that it was to be the last section).

Whatever is written by "experts," the 1924 edition was not "immensely popular": the people of Egypt always preferred other editions: in the 1920s and '30s 522 pages written by Muṣṭfā Naẓīf Qadirghali (still reprinted in its Ottoman gestalt in the 1950s), since 1975 (till today) the Šamarlī (as well on 522 pages), after 1976 for a decade Muṣḥaf al-Azhar aš-Šarīf (525 pages, several sizes), since 1980 editions written by ʿUṯmān Ṭaha (on 604 pages). The people of Egypt never took to the 844 pages of the "revolutionary" King Fuʾād Edition (18,5 x 26 x 5 cm). The 1924 edition was never reprinted (the 1955 Peking edition has the same text for the qur'ān and the information, but adds a title page, suppresses the dedication to the king, has different headers, different frames etc).

To understand what went on, it helps to know that Egypt was part of the Ottoman Empire from January 1517 to November 1914. Soon after, the government found "faults" in Ottoman maṣāḥif and asked the chief qārī of Egypt to prepare a modern Egyptian edition; a former director of the Arabic department of the Ministry of Education and two professors from the Teachers Training Center Nāṣarīya (located next door) were to assist him.

It is important to note that India and the Maghreb had largely kept the qurʾān orthography of the tenth century, or they had reverted to the old spelling already sometime before.

When Hythem Sidky writes in his review article:

On the other hand, in Persia and (to a lesser extent) in the Ottoman Empire, the spelling had become closer to the "normal" spelling of Arabic ‒ this process has been labelled "classification" = writing as if the qurʾān had been put on vellum by Sībawaih & Co.

1924 brought no revolution. Already in 1890, a muṣḥaf had been printed that was pretty close to the spelling of 1924 ‒ actually closer to ad-Dānī (not to his pupil Ibn Naǧaḥ, preferred in the Maghrib).

Five years later a qurʾān "bir-rasm al-ʿUṯmānī" was type printed on the margin of a commentary.

The scholar behind the reform Abū ʿId Riḍwān al-Muḫallalātī had died the year before, but the makers of the King Fuʾād Edition pay tribute to him.

In 1930 Gotthelf Bergsträßer met Muḥammad b. ʿAlī b. Ḫalaf al-Ḥusainī al-Mālikī aṣ-Ṣaʿīdī al-Ḥaddād (and his successor ʿAlī b. Muḥammad b. Ḥasan b. Ibrāhīm al-Maṣrī aḍ-Ḍabbāʿ d.1380/ 1961). In "Die Koranlesung in Kairo" (Der Islam XX, 1932. p. 5) he writes:

Marijn van Putten recently tweeted:

I go further: al-Ḥaddād was not even aware of the "Ḥijāzī" manuscripts. He didn't "get it wrong", because he did not try to do what MvP thinks he tried. He assumed that the Maġribī scholars had preserved the ʿUṯmānic rasm.

Don't get me wrong. I am contradicting PvM not because he is particularly stupid, but because he is especially important. Whereas most scholars are just Nöldeke IV or Spitalerin 1.6 (or try to become those), MvP prepares new paths.

But MvP's "The Cairo Edition" (and Sidky's "CE") is stupidity pure:

There are more than a thousand Cairo editions, but the King Fuʾād / Survey Authority Edition is a Giza edition, not Cairo.

Marijn van Putten and Hythem Sidky are not stupid, they are just like the people of Tiznit, who call Duc Anh Vu, the only Vietnamese in town, "Chinese", they do not know from which city he is, they do not need to know, "Asia something" is good enough for them. Experts in early quranic fragments do not have to visit the hundreds of bookshops in Cairo, Karachi or Jakarta ‒ but still it would be nice if they stopped calling Duc Anh Vu "Chinese" (or the King Fuʾād Edition "CE") ‒ he/it is not.

Let me admit that the edition printed 1924 in Giza, bound and blind-stamped in Būlāq "ṭabʿat al-ḥukūma al-miṣrīya sanat 1343 hijrīya" (1924/5), without a title on the cover, the spine, without a title page, is important, but not as important as many think and not for the reasons given.

طبعة الحكومية المصرّية

-- . --

١٣٤٣ هجرّية

سـنة

The edition is not and never was The Standard, it has not spread Ḥafṣ ʿan ʿĀṣim (BTW it is not an "Azhar Edition," and no "King Farūq edition" was published in 1936 or anytime). It was not the first that proclaims to follow the ʿUṯmānic rasm, and it is not type printed ‒ it is typeset, offset printed (planographic printing just as lithography). It is not the first with a postscript (Lucknow copies from the 1870s onward and the Muḫallalātī Cairo 1890 print have postscripts ‒ although the latter is sometimes bound as preface ‒ the numbers on the gatherings {malāzim, sg.: mulzama} show that it was to be the last section).

Whatever is written by "experts," the 1924 edition was not "immensely popular": the people of Egypt always preferred other editions: in the 1920s and '30s 522 pages written by Muṣṭfā Naẓīf Qadirghali (still reprinted in its Ottoman gestalt in the 1950s), since 1975 (till today) the Šamarlī (as well on 522 pages), after 1976 for a decade Muṣḥaf al-Azhar aš-Šarīf (525 pages, several sizes), since 1980 editions written by ʿUṯmān Ṭaha (on 604 pages). The people of Egypt never took to the 844 pages of the "revolutionary" King Fuʾād Edition (18,5 x 26 x 5 cm). The 1924 edition was never reprinted (the 1955 Peking edition has the same text for the qur'ān and the information, but adds a title page, suppresses the dedication to the king, has different headers, different frames etc).

To understand what went on, it helps to know that Egypt was part of the Ottoman Empire from January 1517 to November 1914. Soon after, the government found "faults" in Ottoman maṣāḥif and asked the chief qārī of Egypt to prepare a modern Egyptian edition; a former director of the Arabic department of the Ministry of Education and two professors from the Teachers Training Center Nāṣarīya (located next door) were to assist him.

It is important to note that India and the Maghreb had largely kept the qurʾān orthography of the tenth century, or they had reverted to the old spelling already sometime before.

When Hythem Sidky writes in his review article:

"the [modern] orthographic standard of classical Arabic ... characterized nearly all muṣḥafs" before 1924 (Book Review of Daniel Alan Brubaker, Corrections in Early Qurʾānic Manuscripts in Al-ʿUṣūr al-Wusṭā 27, 2019. p. 276),he is completely wrong: There was not a single muṣḥaf written like classical Arabic and the majority (in Africa, in India, in Nusantara, in Central Asia) wrote according to ad-Dānī or close to his Muqniʿ. Egyptian ʿulamāʾ had been aware of the old spelling; books of ad-Dānī (on the rasm, on the readings, on verse numbers) were taught and studied.

On the other hand, in Persia and (to a lesser extent) in the Ottoman Empire, the spelling had become closer to the "normal" spelling of Arabic ‒ this process has been labelled "classification" = writing as if the qurʾān had been put on vellum by Sībawaih & Co.

1924 brought no revolution. Already in 1890, a muṣḥaf had been printed that was pretty close to the spelling of 1924 ‒ actually closer to ad-Dānī (not to his pupil Ibn Naǧaḥ, preferred in the Maghrib).

Five years later a qurʾān "bir-rasm al-ʿUṯmānī" was type printed on the margin of a commentary.

The scholar behind the reform Abū ʿId Riḍwān al-Muḫallalātī had died the year before, but the makers of the King Fuʾād Edition pay tribute to him.

In 1930 Gotthelf Bergsträßer met Muḥammad b. ʿAlī b. Ḫalaf al-Ḥusainī al-Mālikī aṣ-Ṣaʿīdī al-Ḥaddād (and his successor ʿAlī b. Muḥammad b. Ḥasan b. Ibrāhīm al-Maṣrī aḍ-Ḍabbāʿ d.1380/ 1961). In "Die Koranlesung in Kairo" (Der Islam XX, 1932. p. 5) he writes:

Quelle für diesen Konsonantentext sind natürlich nicht Koranhandschriften, sondern die Literatur über ihn; er ist also eine Rekonstruktion, das Ergebnis einer Umschreibung des üblichen Konsonantentextes in die alte Orthographie nach den Angaben der Literatur. Benützt ist dafür ...I think Bergsträßer is wrong, and Sidky is wrong, when he writes that the 1924 Gizeh print relied on rasm works. Yes, its makers write in the postface, that they did, but I am convinced, that in practice al-Ḥusainī al-Ḥaddad al-Mālikī just copies a Warš muṣḥaf changing it to Ḥafṣ ‒ which is easy for the chief qārī, he knows the differences between the two readings by heart; the pause signs are his creation, the verse numbers are Kufic based on works by aš-Šāṭibī and al-Muḫallalātī.

of course the source for the consonantal text are not manuscripts, but the literature about it; hence it is a reconstruction, the result of transforming the [then a.s.] common consonantal text into the old orthography according to the literature, foremost Maurid aẓ-Ẓamʾān by [abu ʿAbdallāh] Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad [ibn Ibrāhīm] al-Ummawī aš-Šarīšī known as al-Ḫarrāz and its commentary by ... and a further commentary for the marks (ḍabṭ)

Marijn van Putten recently tweeted:

The Cairo Edition clearly attempted to get to the original rasm, and was successful to a remarkable extent, but occasionally failed to get it right, as is clear from manuscript evidence. [Sometimes] Rasm works (or, at least those consulted by the committee of the Cairo edition) consistently get it wrong in comparison with the actual manuscript evidence.As I see it, MvP makes several mistakes: there was no committee work; of the four editors mentioned there was only ONE ʿālim, the others had not the slightest idea about writing and reading a muṣḥaf, they just stood for the Giza print as "government/ministry of education muṣḥaf". The editor al-Ḥusainī al-Ḥaddād did not scrutinize qurʾān manuscripts, either ancient nor recent. He just adapted a Warš muṣḥaf with verse numbers according to Medina II to the transmission of Ḥafṣ with Kūfī numbers and his own pause signs (based on the system used in the East). Although he writes in the afterword that the rasm is based on Ibn Najāḥ, it does not follow him all the time; I have the impression that it is not primarily based on rasm works (by ad-Dānī, Ibn Najāḥ, al-Ḫarrāz, aš-Šāṭibī, al-Saḫāwī or al-Murādī al-Balansī, nor the Indian al-Arkātī) but on a contemporary muṣḥaf.

I go further: al-Ḥaddād was not even aware of the "Ḥijāzī" manuscripts. He didn't "get it wrong", because he did not try to do what MvP thinks he tried. He assumed that the Maġribī scholars had preserved the ʿUṯmānic rasm.

Don't get me wrong. I am contradicting PvM not because he is particularly stupid, but because he is especially important. Whereas most scholars are just Nöldeke IV or Spitalerin 1.6 (or try to become those), MvP prepares new paths.

But MvP's "The Cairo Edition" (and Sidky's "CE") is stupidity pure:

There are more than a thousand Cairo editions, but the King Fuʾād / Survey Authority Edition is a Giza edition, not Cairo.

Marijn van Putten and Hythem Sidky are not stupid, they are just like the people of Tiznit, who call Duc Anh Vu, the only Vietnamese in town, "Chinese", they do not know from which city he is, they do not need to know, "Asia something" is good enough for them. Experts in early quranic fragments do not have to visit the hundreds of bookshops in Cairo, Karachi or Jakarta ‒ but still it would be nice if they stopped calling Duc Anh Vu "Chinese" (or the King Fuʾād Edition "CE") ‒ he/it is not.

Came across a quote by Martha C. Nussbaum, an excellent philosopher and essayist, referring to Ruhollah Musawi Khomeini as "the Ayatollah," because she does not know that there are more than 5000 Ayatollahs in Iran. It seems that some do not know that there are more than a thousand Cairo editions ‒ or they just don't care.

Thursday, 5 December 2019

Neuwirth's Nonsense: Qur'ān vs. Muṣḥaf

Once you are a diva, commoners don't prevent

you any more from writing nonsense.

Be it that they don't dare to,

be it that they think: When the goddess says so, it must be so.

But a truism for "its emergent phase".

For the "Islamic tradition" it should be easy to give lots of sources,

but does the Islamic tradition really see al-qurʾān as a communication?

Do Muslims really call the Divine Book al-muṣḥaf?

No and No.

Utter Nonsense! True Neuwirth.

Yes, Muslims make distinctions:

al-kitāb ‒ al-qurʾān ‒ al-muṣḥaf

But al-qurʾān is not a process.

It can be recitation (the core meaning of the word).

It can be the same as al-Kitāb, the divinely authored Book in heaven.

al-muṣḥaf is the rather mundane materialisation, not on a tablet in heaven,

but between two covers on earth ‒ be it written by hand, be it printed.

Before reading Neuwirth ‒ and after reading her ‒ I thought that they call the divine book al-kitāb.

If my credentials are too weak, you might rather believe Yasin Dutton:

you any more from writing nonsense.

Be it that they don't dare to,

be it that they think: When the goddess says so, it must be so.

The Qur’ān in its emergent phase is not a pre-meditated, fixed compilation, a reified literary artefact, but a still-mobile text reflecting an oral theological-philosophical debate between diverse interlocutors of various late antique denominations.So far: no problem.

Angelika Neuwirth, "Two Faces of the Qurʾan" in Kelber, Sanders (eds.): Oral-Scribal Dimensions ... Eugene, OR: Cascade 2016. p.172

But a truism for "its emergent phase".

Islamic tradition, however, does distinguish between the (divinely) “authored Book,” labelled al-muṣḥaf ... and the Qur’ānic communication process, labelled al-qur’ān.No footnote. No sources given.

first in Oral Tradition, 25/1 (2010): 141-156, here: 143

later in Werner H. Kelber, Paula A. Sanders( eds.) Oral-Scribal Dimensions of Scripture, Piety, and Practice. Eugene, OR: Cascade 2016. pp. 170-187, here: 173?

For the "Islamic tradition" it should be easy to give lots of sources,

but does the Islamic tradition really see al-qurʾān as a communication?

Do Muslims really call the Divine Book al-muṣḥaf?

No and No.

Utter Nonsense! True Neuwirth.

Yes, Muslims make distinctions:

al-kitāb ‒ al-qurʾān ‒ al-muṣḥaf

But al-qurʾān is not a process.

It can be recitation (the core meaning of the word).

It can be the same as al-Kitāb, the divinely authored Book in heaven.

al-muṣḥaf is the rather mundane materialisation, not on a tablet in heaven,

but between two covers on earth ‒ be it written by hand, be it printed.

Before reading Neuwirth ‒ and after reading her ‒ I thought that they call the divine book al-kitāb.

If my credentials are too weak, you might rather believe Yasin Dutton:

we need to distinguish between kitāb, qurʾān and muṣḥaf, which we can see as three aspects of the same thing. Kitāb, we would say, is the divinely-preserved ‘original’, which, as God’s speech (kalām) and therefore one of the divine attributes, is, strictly speaking, indefinable in human terms. In a sense it belongs to a different realm: it is ‘that book’ (dhālika l-kitāb; Q. 2. 2) rather than ‘this Qurʾān’ (hādhā al-qurʾān; e.g. Q. 6. 19, 10. 37, etc). It is, as the Qurʾān says, a book that has been sent down in the form of a qurʾān in the Arabic language (kitābun fuṣṣilat āyātuhu qurʾānan ʿarabiyyan [‘a book whose āyas (‘signs’, ‘verses’) have been demarcated (or ‘clarified’) in the form of an Arabic Qurʾān’] Q. 41. 3) so that it can be understood by people. One could say that it is from the out-of-time and comes into the in-time on the heart, and then the tongue, of the Messenger: ‘The Trustworthy Spirit brought it down onto your heart for you to be one of the warners, in a clear Arabic tongue’ (Q. 26. 193–5). But in doing so it takes on some of the characteristics of ordinary human speech: it is in their language ..."ORALITY, LITERACY AND THE 'SEVEN AḤRUF' ḤADĪTH" in Journal of Islamic Studies, Vol. 23, No. 1 (January 2012). pp38ff.

we could say that the kitāb of Allah gets expressed as qurʾān on the tongue of the Messenger, and then as ṣuḥuf and maṣāḥif by the pens of the Muslims—and all are aspects of one and the same thing. Wa-l-lāhua aʿlamu bi-l-ṣawāb.

Friday, 29 November 2019

al-muzzammil 20, page 775

In Kein Standard I show 26 images of prints by the Amiriyya and reprints, clones of surat al-muzzammil verse 20.

I started with the two copies held by the National (Prussian) Library: the first print from 1924 and a print with reduced margin from 1929.

American university libraries hold other copies. So here are page 775 from 1925:

and 1930:

I started with the two copies held by the National (Prussian) Library: the first print from 1924 and a print with reduced margin from 1929.

American university libraries hold other copies. So here are page 775 from 1925:

and 1930:

Thursday, 28 November 2019

van Putten's QCT again

"QCT" is a bad name for a bad concept.

bad name ...

because many of its letters are not consonants.

Aḥmad al-Jallad was kind enough to inform me that

these letters ARE consonants USED as something else:

consonants "repurposed", consonants functioning as vowels.

In my philosophy (and that of Wittgenstein II) this makes no sense:

words ARE what they are USED for = they have no essence apart from the way we use them.

But this is not very important.

Important is whether the text

we are dealing with

is purely consonantal.

And unlike all Safaitic, Hismaic, and Thamudic texts

the Early Quranic Text is clearly not purely consonantal.

van Putten's term QCT for the Common Early QT is wrong

because many of its letters stand for long vowels,

because many of its letters stand for diphtongs,

because one letter stand for end of word (alif after waw),

because many of its letters stand for short vowels,

‒ not only those that are marked in Giza24 by a circle (in IndoPak with no sign),

but those seen now as seat/carrier of hamza.

bad concept

Marijn van Putten:

When I look at van Putten's slide, I get what he means by "the Quranic text as we find it today":

Ḥafṣ without the "countless" marks.

The QCT can not be "identical ... to the reading traditions" ‒ because ‒ as I have shown before ‒ many skeletal words do have different dots;

skeletal words stand for different words ‒ they are identical to themselves, NOT to their brothers in another reading.

Here just some words from the first suras differently dotted for Ḥafṣ and Warš:

ءَاتَيۡتُكُم ءَاتَيۡتنَٰكُم (3:81) تَعۡمَلُونَ يَعۡمَلُونَ (2:85) تَعۡمَلُونَ يَعۡمَلُونَ (2:140) (3:188) تَحۡسَبَنَّ تَحۡسِبَنَّ (4:73) تَكُن يَكُن (2:259) نُنشِزُهَا نُنشِرُهَا (2:58) يُغۡفَرۡ نَّغۡفِرۡ (2:165) يَرَى تَرَى ترونهم يرونهم (3:13) (3:83) يَبۡغُونَ تَبۡغُونَ يُرۡجَعُونَ تُرۡجَعُونَ(3:83) (3:115)يَفۡعَلُوا تَفۡعَلُوا يُكۡفَرُوهُ تُكۡفَرُوهُ (3:115) يَجۡمَعُونَ تَجۡمَعُونَ (3:157) (2:271) يُكَفِّرُ نُكَفِّر (3:57) فَنُوَفِّيهمُ فَنُوَفِّيهمُۥۤ (4:13) يُدۡخِلۡهُ نُدۡخِلۡهُ (4:152) يُؤۡتِيهِمۡ نُوتِيهِمُۥٓ

Some other examples:

4:94

fa-tabayyanū

fa-taṯabbatū

2:74, 85, 144

yaʾmalūn

taʾmalūn

2:219

kabīr

kaṯīr

2:259

nanšuruhā

nunšizuhā

3:48 wa-nuʿallimuhu

wa-yuʿallimuhu

Yes, the rasm was not meant to be a naked drawing,

people did read it.

But to assume they read Ḥafṣ is just stupid.

Better a naked skeleton than a text fleshed out in ONE way.

It would be nice to have a COMMON Skeletal Text with all the dots,

on which ALL canonical readers agree

‒ which requires ihmal signs for rāʾ, dāl, ḫāʾ, final he, ṭāʾ, ṣād and sīn.

Just for those not familiar with ihmal signs:

for all letters V = two bird wings = لا can be used

for ḫāʾ, final he, ṭāʾ, ṣād and sīn a small letter (not unlike the little kāf in end kāf),

and for rāʾ and dāl a dot below tell us: not ǧīm, not ḫāʾ, not ẓāʾ, nod ḍād, not šīn, not zāʾ, not ḏāʾ!

bad name ...

because many of its letters are not consonants.

Aḥmad al-Jallad was kind enough to inform me that

these letters ARE consonants USED as something else:

consonants "repurposed", consonants functioning as vowels.

In my philosophy (and that of Wittgenstein II) this makes no sense:

words ARE what they are USED for = they have no essence apart from the way we use them.

But this is not very important.

Important is whether the text

we are dealing with

is purely consonantal.

And unlike all Safaitic, Hismaic, and Thamudic texts

the Early Quranic Text is clearly not purely consonantal.

van Putten's term QCT for the Common Early QT is wrong

because many of its letters stand for long vowels,

because many of its letters stand for diphtongs,

because one letter stand for end of word (alif after waw),

because many of its letters stand for short vowels,

‒ not only those that are marked in Giza24 by a circle (in IndoPak with no sign),

but those seen now as seat/carrier of hamza.

bad concept

Marijn van Putten:

The QCT is defined as the text reflected in the consonantal skeleton of the Quran, the form in which it was first written down, without the countless … vocalisation marks.

The … QCT is roughly equivalent to … the rasm, the … undotted consonantal skeleton of the Quranic text,

but there is an important distinction. The concept of QCT ultimately assumes that not only the letter shapes, but also the consonantal values are identical to the Quranic text as we find it today.

As such, when ambiguities arise, for example in medial ـثـ ،ـتـ ،ـبـ ،ـنـ ،ـيـ , the original value is taken to be identical to the form as it is found in the Quranic reading traditions today.

When I look at van Putten's slide, I get what he means by "the Quranic text as we find it today":

Ḥafṣ without the "countless" marks.

The QCT can not be "identical ... to the reading traditions" ‒ because ‒ as I have shown before ‒ many skeletal words do have different dots;

skeletal words stand for different words ‒ they are identical to themselves, NOT to their brothers in another reading.

Here just some words from the first suras differently dotted for Ḥafṣ and Warš:

ءَاتَيۡتُكُم ءَاتَيۡتنَٰكُم (3:81) تَعۡمَلُونَ يَعۡمَلُونَ (2:85) تَعۡمَلُونَ يَعۡمَلُونَ (2:140) (3:188) تَحۡسَبَنَّ تَحۡسِبَنَّ (4:73) تَكُن يَكُن (2:259) نُنشِزُهَا نُنشِرُهَا (2:58) يُغۡفَرۡ نَّغۡفِرۡ (2:165) يَرَى تَرَى ترونهم يرونهم (3:13) (3:83) يَبۡغُونَ تَبۡغُونَ يُرۡجَعُونَ تُرۡجَعُونَ(3:83) (3:115)يَفۡعَلُوا تَفۡعَلُوا يُكۡفَرُوهُ تُكۡفَرُوهُ (3:115) يَجۡمَعُونَ تَجۡمَعُونَ (3:157) (2:271) يُكَفِّرُ نُكَفِّر (3:57) فَنُوَفِّيهمُ فَنُوَفِّيهمُۥۤ (4:13) يُدۡخِلۡهُ نُدۡخِلۡهُ (4:152) يُؤۡتِيهِمۡ نُوتِيهِمُۥٓ

Some other examples:

4:94

fa-tabayyanū

fa-taṯabbatū

2:74, 85, 144

yaʾmalūn

taʾmalūn

2:219

kabīr

kaṯīr

2:259

nanšuruhā

nunšizuhā

3:48 wa-nuʿallimuhu

wa-yuʿallimuhu

Yes, the rasm was not meant to be a naked drawing,

people did read it.

But to assume they read Ḥafṣ is just stupid.

Better a naked skeleton than a text fleshed out in ONE way.

It would be nice to have a COMMON Skeletal Text with all the dots,

on which ALL canonical readers agree

‒ which requires ihmal signs for rāʾ, dāl, ḫāʾ, final he, ṭāʾ, ṣād and sīn.

Just for those not familiar with ihmal signs:

for all letters V = two bird wings = لا can be used

for ḫāʾ, final he, ṭāʾ, ṣād and sīn a small letter (not unlike the little kāf in end kāf),

and for rāʾ and dāl a dot below tell us: not ǧīm, not ḫāʾ, not ẓāʾ, nod ḍād, not šīn, not zāʾ, not ḏāʾ!

Monday, 25 November 2019

al-rasm al-ʿUṯmānī vs. "al-rasm al-ʿUṯmānī"

Orientals have a well-established narration about the collection of the qurʾān

and its subsequent dissemination to the central cities of the empire.

Orientalists ‒ keener in scrutinizing real old manuscripts ‒ had the best time ever:

first came the quranic manuscripts from the Great Mosque of San'a'

then came the realisation that a couple of fragments belong together: that they had been one codex in the ʿAmr ibn al-ʿĀṣ mosque in Fustat before being dispersed.

And after studying the famous palimpsest and the fragments in London, Paris, Petersburg Orientalists came away "assuming/knowing" what Muslims had "believed/known" for a long time:

during the caliphate of ʿUṯmān the text has been standardised.

So far, so good.

But the Orientalists made another discovery:

The early manuscripts were not written in the spelling known as "al-rasm al-ʿUṯmānī",

but in what Michael Marx calls "Hijāzī spelling" ‒ implicitly calling the common "rasm al-ʿUṯmānī" "Kūfī spelling"

‒ although one finds some "Hijāzī spelling" ( علا for على

; حتا for حتى ) in Kūfī mss.

In order not to burry the ʿUṭmānic rasm Behnam Sadeghi comes up with a new concept: the morphemo-skeletal text: nevermind the concrete rasm, as long as it is the same morpheme (David, thing, about, until) it is the same text.

I have no problem with that,

but I protest, when someone calls "al-rasm al-ʿUṯmānī" (fixed/discovered/invented about four centuries after ʿUṯmān) al-rasm al-ʿUṯmānī without quotation marks.

You can cling to ad-Dānī's rasm, but please do not call it ʿUṯmānic rasm, because it is not!

"belonging to the ʿUṯmānic text type" is fine:

Persian and Ottoman mss. have the ʿUṯmānic text, but not the "ʿUṯmānic rasm", and the ʿUṯmānic rasm is not known.

and its subsequent dissemination to the central cities of the empire.

Orientalists ‒ keener in scrutinizing real old manuscripts ‒ had the best time ever:

first came the quranic manuscripts from the Great Mosque of San'a'

then came the realisation that a couple of fragments belong together: that they had been one codex in the ʿAmr ibn al-ʿĀṣ mosque in Fustat before being dispersed.

And after studying the famous palimpsest and the fragments in London, Paris, Petersburg Orientalists came away "assuming/knowing" what Muslims had "believed/known" for a long time:

during the caliphate of ʿUṯmān the text has been standardised.

So far, so good.

But the Orientalists made another discovery:

The early manuscripts were not written in the spelling known as "al-rasm al-ʿUṯmānī",

but in what Michael Marx calls "Hijāzī spelling" ‒ implicitly calling the common "rasm al-ʿUṯmānī" "Kūfī spelling"

‒ although one finds some "Hijāzī spelling" ( علا for على

; حتا for حتى ) in Kūfī mss.

In order not to burry the ʿUṭmānic rasm Behnam Sadeghi comes up with a new concept: the morphemo-skeletal text: nevermind the concrete rasm, as long as it is the same morpheme (David, thing, about, until) it is the same text.

I have no problem with that,

but I protest, when someone calls "al-rasm al-ʿUṯmānī" (fixed/discovered/invented about four centuries after ʿUṯmān) al-rasm al-ʿUṯmānī without quotation marks.

You can cling to ad-Dānī's rasm, but please do not call it ʿUṯmānic rasm, because it is not!

"belonging to the ʿUṯmānic text type" is fine:

Persian and Ottoman mss. have the ʿUṯmānic text, but not the "ʿUṯmānic rasm", and the ʿUṯmānic rasm is not known.

Sunday, 17 November 2019

Kūfī verse numbering

It is not wise to repeat hearsay.

But sometimes we do it nevertheless.

Somewhere I had read that in India the Kufī numbering system

has five more verses than the Egyptian Kufī system ‒

without moving any end of verse (therefore both being Kufī),

just by splitting five long verses.

Adrian Alan Brockett wrote that in the 20th century the differences have been reduced

‒ without giving chapter and verse.

But here are four places where India used to differ from Arabia:

4:173, 6:73, 36:34+5 were

4:173+4 , 6:73+4 resp. 36:34

.

.

added later:

2:246 and 41:45 can be different in India from Gizeh24 (Brockett p.29)

BHO had both Kufī and Baṣrī, known 100% like "modern" Kufī.

HOQz, MNQ, (HaRi and ar-Rušdi) had exactly the same Kufī numbers as we have today ‒ like Muṣḥaf al-Muḫallalātī and KFE.

al-Muḫallalātī is even one of the four authorities giving in Hyderabad38:

But sometimes we do it nevertheless.

Somewhere I had read that in India the Kufī numbering system

has five more verses than the Egyptian Kufī system ‒

without moving any end of verse (therefore both being Kufī),

just by splitting five long verses.

Adrian Alan Brockett wrote that in the 20th century the differences have been reduced

‒ without giving chapter and verse.

But here are four places where India used to differ from Arabia:

4:173, 6:73, 36:34+5 were

4:173+4 , 6:73+4 resp. 36:34

.

.

In Encyclopedia of Islam II A.T.Welch writes that in India 18:18 was split in two. I can not confirm this. He further writes that Pickthall has this split verse ‒ correct ‒, and that it was only changed in 1976 ‒ it was changed in 1938.BTW, the Ottomans did not have here an additional end of verse:

added later:

2:246 and 41:45 can be different in India from Gizeh24 (Brockett p.29)

BHO had both Kufī and Baṣrī, known 100% like "modern" Kufī.

HOQz, MNQ, (HaRi and ar-Rušdi) had exactly the same Kufī numbers as we have today ‒ like Muṣḥaf al-Muḫallalātī and KFE.

al-Muḫallalātī is even one of the four authorities giving in Hyderabad38:

Thursday, 14 November 2019

Persian / Iran

In one of my first German posts

I show that ʿUṯmān Ṭaha writes less calligraphicly than the 1924 Egyptian government print: UT has a strict base line,

no mīm without white space in the middle = no mīm below lām: the next letter is always to the left. In the UT style

vowel signs are always near "their" letter <--> in traditional Ottoman and Persian style they must

only be in the right order.

All in all, ʿUṯmān Ṭaha is very close to the style of the Amiriyya = a simple Ottoman style.

In a German text I focus on orthography, giving most attention to the Maghrebian-Arab and to the Pakistani-Indian ones

and consequently on the new Arab calligraphic style and the new Pakistani-Indian one. Of course, I display examples from Morocco, from the Sudān, from Russia-Tartaristan as well -- and the earlier Indian style from Lucknow plus example from Punjab, from Bengal and Kerala.

I show many examples from Turkey and the Mašriq, but from Iran, I show mainly Nastaʿliq ones.

Here you see the normal Persian "qur'anic" style, taken from old maṣāḥif, all recently reproduced.

although written by three different (famous) writers, they are similar.

Note in the bottom right, that (like sometimes in India) wa is separated from the word to which it "belongs", something forbidden in Arabic.

Here two more examples of wrong wa- at the end of a line. I find the first example shocking because the silent alif-waṣl is separated from its vowel /a/.

Fist images from four Iranian ʿUṯmān Ṭāhā editions:

Now an Arab-Persian version which the original ʿUṯmān Ṭāhā writing, but

in 11 lines instead of 15 -- and again twice the grave sin against Arab orthography:

wa- at the end of line:

Now an Arab-Persian version which the original ʿUṯmān Ṭāhā writing, but

in 11 lines instead of 15 -- and again twice the grave sin against Arab orthography:

wa- at the end of line:

Here a more traditional print: 604 pages, a Persan style close to ʿUṯmān Ṭāhā, mostly with the Persian help signs:

All in all, ʿUṯmān Ṭaha is very close to the style of the Amiriyya = a simple Ottoman style.

In a German text I focus on orthography, giving most attention to the Maghrebian-Arab and to the Pakistani-Indian ones

and consequently on the new Arab calligraphic style and the new Pakistani-Indian one. Of course, I display examples from Morocco, from the Sudān, from Russia-Tartaristan as well -- and the earlier Indian style from Lucknow plus example from Punjab, from Bengal and Kerala.

I show many examples from Turkey and the Mašriq, but from Iran, I show mainly Nastaʿliq ones.

Here you see the normal Persian "qur'anic" style, taken from old maṣāḥif, all recently reproduced.

although written by three different (famous) writers, they are similar.

Note in the bottom right, that (like sometimes in India) wa is separated from the word to which it "belongs", something forbidden in Arabic.

Here two more examples of wrong wa- at the end of a line. I find the first example shocking because the silent alif-waṣl is separated from its vowel /a/.

Fist images from four Iranian ʿUṯmān Ṭāhā editions:

Now an Arab-Persian version which the original ʿUṯmān Ṭāhā writing, but

in 11 lines instead of 15 -- and again twice the grave sin against Arab orthography:

wa- at the end of line:

Now an Arab-Persian version which the original ʿUṯmān Ṭāhā writing, but

in 11 lines instead of 15 -- and again twice the grave sin against Arab orthography:

wa- at the end of line:

Here a more traditional print: 604 pages, a Persan style close to ʿUṯmān Ṭāhā, mostly with the Persian help signs:

Wednesday, 13 November 2019

never trust a reprint

never trust a reprint ... you did not "improve" yourself!

Köҫök Hafiz Osman = Haǧǧ Ḥāfiẓ ʿUṯmān Ḫalīfa QayišZāde an-Nūrī al-Burdurī (Hac Hattat Kayışzade Hafis Osman Nûri Efendi Burdurlu, d. 4.Ramaḍān 1311/ 11.March 1894) wrote 106 1/2 maṣāḥif.

BülÜk Hafiz Osman (1052/1642‒1110/1698) wrote only 25 (but many En’am-ı Şerif, and hilyeler) One on 815 pages (plus prayer, index, colophon) was often reprinted in Syria ‒ in Egypt mostly as reference in lengthy commentaries.

In Turkey one finds hundreds of different "reprints".

They never give a true picture of the original.

On the left you see a Syrian print (HO the Elder, twelve lines per pages, 815 pages) from before 1950 with many signs that are later missing:

small hā' and yā' for five and ten (fifteen, twenty and so on)

small two letter signs always including bā' giving information about Baṣrī verse numbering

small dotless letters under or above a dotless letter stressing its dotlessnes.

In the middle (HO the Younger) I have highlighted two places:

the first was changed by the modern Turkish editors (see the page on the right), because the letters and signs do not follow right-to-left clearly enough.

the second one (modern edition) show a different rasm ‒

a rasm by the way used by the same calligrapher in the other (the "Syrian") muṣḥaf:

Köҫök Hafiz Osman = Haǧǧ Ḥāfiẓ ʿUṯmān Ḫalīfa QayišZāde an-Nūrī al-Burdurī (Hac Hattat Kayışzade Hafis Osman Nûri Efendi Burdurlu, d. 4.Ramaḍān 1311/ 11.March 1894) wrote 106 1/2 maṣāḥif.

BülÜk Hafiz Osman (1052/1642‒1110/1698) wrote only 25 (but many En’am-ı Şerif, and hilyeler) One on 815 pages (plus prayer, index, colophon) was often reprinted in Syria ‒ in Egypt mostly as reference in lengthy commentaries.

In Turkey one finds hundreds of different "reprints".

They never give a true picture of the original.

On the left you see a Syrian print (HO the Elder, twelve lines per pages, 815 pages) from before 1950 with many signs that are later missing:

small hā' and yā' for five and ten (fifteen, twenty and so on)

small two letter signs always including bā' giving information about Baṣrī verse numbering

small dotless letters under or above a dotless letter stressing its dotlessnes.

In the middle (HO the Younger) I have highlighted two places:

the first was changed by the modern Turkish editors (see the page on the right), because the letters and signs do not follow right-to-left clearly enough.

the second one (modern edition) show a different rasm ‒

a rasm by the way used by the same calligrapher in the other (the "Syrian") muṣḥaf:

Monday, 4 November 2019

the script

Whereas English is written with

A a B b C c D d E e

F f G g H h I i J j

K k L l M m N n O o

P p Q q R r S s T t

U u V v W x , ; . :

! ? " - 1 2 3 4 5 6

7 8 9 0 ( ) [ ] / \

% & # ' + * ~ ^ { }

(80 chars)

the first qurʾān manuscripts just have

ا ٮ ح د ر و ه ط ك ل

م س ص ع ڡ ڡ ٯ ع ص س

* م ل ك ـه ح ٮ ں ى لا

(30 chars)

Most people know that the earliest manuscripts

do not have diacritical dots, no ḥamza sign, no numerals,

no shadda, no hyphen, colon, just an end of aya sign,

but hardly anybody is aware of two facts:

There is no space between words.

{Th. Bauer is wrong ("Words are set apart by greater spaces" in Peter T. Daniel, ed. p. 559).}

There is no hyphenation: end of line is insignificant.

Start letters and End letters are distinct letters

(although standing for the same sound, they carry a different meaning), whereas Start and Middle forms, End and Iso forms are "just" a consequence of the preceding letter.

As "conservative, liberals, god" are different from "Conservative, Liberals, God"

= A and a are not the same letter

ح and ح are not the same letter

Just as capital letters carry a meaning (person, majesty, name, start of a sentence--in German: noun),

End (resp. Iso) carries the meaning: "end of the word".

Therefore there was no "space between words" -- or was it the other way round?

And because there is no End-waw (and because two alifs can not stand WITHIN a word),

after waw at the end of a word an alif was added: the word border runs between the two alifs.

Lakhdar-Ghazal saw a core letter and end markers:

ح ع م

ٮ ل ى

س ص ں

That does not work for all letters and not for all calligraphic styles.

Unicode sees colon, space, Non-Joiner as triggering the end form of ONE letter.

That is clearly wrong for the early manuscripts.

Bauer's "each letter may occur in four different positions: initial, medial, final, and isolated" is a truism, but it shows, that he noticed that the common statement "each letter has four forms/graphic shapes" is untenable, both because many have only one form (in typewriter script), and many have more than twenty (in "high" naskhi). Not trivial is "the common designation of the Arabic script as "consonantal" is incorrect, since the long vowels are represented but consonant gemination is not." (Bauer in Daniel p.561) -- although not ALL long vowels are represented (as Bauer knows of course), and some short vowels are represented and diphthongs as well.

A a B b C c D d E e

F f G g H h I i J j

K k L l M m N n O o

P p Q q R r S s T t

U u V v W x , ; . :

! ? " - 1 2 3 4 5 6

7 8 9 0 ( ) [ ] / \

% & # ' + * ~ ^ { }

(80 chars)

the first qurʾān manuscripts just have

ا ٮ ح د ر و ه ط ك ل

م س ص ع ڡ ڡ ٯ ع ص س

* م ل ك ـه ح ٮ ں ى لا

(30 chars)

Most people know that the earliest manuscripts

do not have diacritical dots, no ḥamza sign, no numerals,

no shadda, no hyphen, colon, just an end of aya sign,

but hardly anybody is aware of two facts:

There is no space between words.

{Th. Bauer is wrong ("Words are set apart by greater spaces" in Peter T. Daniel, ed. p. 559).}

There is no hyphenation: end of line is insignificant.

Start letters and End letters are distinct letters

(although standing for the same sound, they carry a different meaning), whereas Start and Middle forms, End and Iso forms are "just" a consequence of the preceding letter.

As "conservative, liberals, god" are different from "Conservative, Liberals, God"

= A and a are not the same letter

ح and ح are not the same letter

Just as capital letters carry a meaning (person, majesty, name, start of a sentence--in German: noun),

End (resp. Iso) carries the meaning: "end of the word".

Therefore there was no "space between words" -- or was it the other way round?

And because there is no End-waw (and because two alifs can not stand WITHIN a word),

after waw at the end of a word an alif was added: the word border runs between the two alifs.

Lakhdar-Ghazal saw a core letter and end markers:

ح ع م

ٮ ل ى

س ص ں

That does not work for all letters and not for all calligraphic styles.

Unicode sees colon, space, Non-Joiner as triggering the end form of ONE letter.

That is clearly wrong for the early manuscripts.

Bauer's "each letter may occur in four different positions: initial, medial, final, and isolated" is a truism, but it shows, that he noticed that the common statement "each letter has four forms/graphic shapes" is untenable, both because many have only one form (in typewriter script), and many have more than twenty (in "high" naskhi). Not trivial is "the common designation of the Arabic script as "consonantal" is incorrect, since the long vowels are represented but consonant gemination is not." (Bauer in Daniel p.561) -- although not ALL long vowels are represented (as Bauer knows of course), and some short vowels are represented and diphthongs as well.

Saturday, 2 November 2019

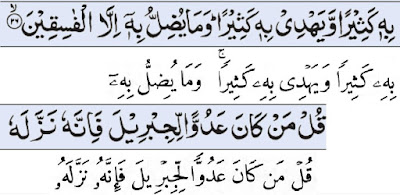

don't confuse!

Perception is multilayered.

Some "see" blue, black and white.

others see strokes and dots,

others Arab words, or words from the beginning of the qurʾān or (among other things) 18 "dagger alifs". I see only nine.

A "dagger alif" is a small alif, an Ersatzalif (supplementary alif)

or a Wandelalif (transforming alif).

The similar looking signs in the "Indian" muṣḥaf from Medina

are no alifs, but fatḥas, standing fatḥas or turned fatḥas,

not letters but vowel signs.

I fail to understand, how anybody can confuse a sign that sits on its letter (or near its ascender)

with a letter that follows a letter+vowelsign-combination.

Once one knows that in the African notation there must be a ḥarf al-madd to lengthen the vowel,

whereas in the Asian notation fatḥa, kasra, ḍamma each have a turned variant for the long vowel,

one SEEs the difference.

Whoever does confuse long vowel sign and Ersatz letter is blind.

In the last line: two Wandelalifs:

there is a ḥarf al-madd, but the wrong one: instead of alif (expected after fatḥa): waw resp. yāʾ here the small alif transforms waw resp. yāʾ into alif. (In the blue line above: (long) standing fatḥa again.)

So not 18 dagger alifs, just seven Ersatzalif plus two Wandelalif.

Not convinced?

Look at these examples.

If you don't see "arguments", study something else (you are not made to study the writing of maṣāḥif).

Here the text from the King Fuad Edition about the small letters (among them "dagger alif"):

And about fatḥa, standing fatḥa, kasra, standing kasra, ḍamma and turned ḍamma.

Some "see" blue, black and white.

others see strokes and dots,

others Arab words, or words from the beginning of the qurʾān or (among other things) 18 "dagger alifs". I see only nine.

A "dagger alif" is a small alif, an Ersatzalif (supplementary alif)

or a Wandelalif (transforming alif).

The similar looking signs in the "Indian" muṣḥaf from Medina

are no alifs, but fatḥas, standing fatḥas or turned fatḥas,

not letters but vowel signs.

I fail to understand, how anybody can confuse a sign that sits on its letter (or near its ascender)

with a letter that follows a letter+vowelsign-combination.

Once one knows that in the African notation there must be a ḥarf al-madd to lengthen the vowel,

whereas in the Asian notation fatḥa, kasra, ḍamma each have a turned variant for the long vowel,

one SEEs the difference.

Whoever does confuse long vowel sign and Ersatz letter is blind.

In the last line: two Wandelalifs:

there is a ḥarf al-madd, but the wrong one: instead of alif (expected after fatḥa): waw resp. yāʾ here the small alif transforms waw resp. yāʾ into alif. (In the blue line above: (long) standing fatḥa again.)

So not 18 dagger alifs, just seven Ersatzalif plus two Wandelalif.

Not convinced?

Look at these examples.

If you don't see "arguments", study something else (you are not made to study the writing of maṣāḥif).

Here the text from the King Fuad Edition about the small letters (among them "dagger alif"):

And about fatḥa, standing fatḥa, kasra, standing kasra, ḍamma and turned ḍamma.

Friday, 25 October 2019

rasm ‒ consonantal skeleton?

The most common translation for rasm

"consonantal skeleton" is wrong.

Look at the 22nd word of 3:195 واودوا

six letters,

definitely not six consonants.

On the sound level

Arabic, like any language,

has sonants and con-sonants.

But on the sign level,

there are just letters.

It doesn't make sense to talk of Phoenician, Arabic, Semitic consonant letters.

Only once there are sonants/vowels, there can be con-sonants/not sounding on their own.

Since Greeks speak no ḥ, they used the letter ḥēt for ē

Jota for ī, changed ʿain into Omikron, waw into Ypsilon (ū).

When you look into early qurʾān manuscripts,

you will see the letters function as end of word maker &

as long vowels & as diphthongs (ḥurūf al-madd wa'l-līn)

& as short vowels,

not only in the common اولٮك and the less frequent أولوا۠ but in ساورىكم

(7:145, 21:37), لاوصلٮٮكم

(7:124, 20:71, 26:49) and

in rare words like وملاٮه (7:103 + 11:97 + 43:46 ) IPak: وَمَلَائِهٖ / وَمَلَا۠ئِهٖ Q52 : وَمَلَإِيْهِۦ

and اڡاىں (3:144 + 21:34)

IPak: افَائِنۡ / افَا۠ئِنْ Q52: اَفإي۠ن .

Modern readers may perceive two silent letters:

one carrying a hamza,

one otiose.

Originally they stood for ayi or a'i or aʾi --

definitely for short vowels.

Both words are written in IPak with silent alif + yāʾ-hamza

in Q52 with alif-hamza + silent yāʾ.

Add to this alif as akkusativ marker (at the end), as question marker at the beginning, hāʾ (tāʾ marbūṭa) as femining marker

(plus wau as name marker at the end outside the qurʾān عمرو)

and common words like انا.

So, to call all letters "consonants", makes no sense.

To call the rasm "consonantal" is wrong.

Call it: skeleton,

letter skeleton,

basic letters,

skeletal text,

stroke,

drawing.

Unfortunately most academics repeat what their predecessors wrote,

they can't look for them*selves, don't mention thinking for them*selves --

whether female, male, trans*gender or non*binary.

"consonantal skeleton" is wrong.

Look at the 22nd word of 3:195 واودوا

six letters,

definitely not six consonants.

On the sound level

Arabic, like any language,

has sonants and con-sonants.

But on the sign level,

there are just letters.

It doesn't make sense to talk of Phoenician, Arabic, Semitic consonant letters.

Only once there are sonants/vowels, there can be con-sonants/not sounding on their own.

Since Greeks speak no ḥ, they used the letter ḥēt for ē

Jota for ī, changed ʿain into Omikron, waw into Ypsilon (ū).

When you look into early qurʾān manuscripts,

you will see the letters function as end of word maker &

as long vowels & as diphthongs (ḥurūf al-madd wa'l-līn)

& as short vowels,

not only in the common اولٮك and the less frequent أولوا۠ but in ساورىكم

(7:145, 21:37), لاوصلٮٮكم

(7:124, 20:71, 26:49) and

in rare words like وملاٮه (7:103 + 11:97 + 43:46 ) IPak: وَمَلَائِهٖ / وَمَلَا۠ئِهٖ Q52 : وَمَلَإِيْهِۦ

and اڡاىں (3:144 + 21:34)

IPak: افَائِنۡ / افَا۠ئِنْ Q52: اَفإي۠ن .

Modern readers may perceive two silent letters:

one carrying a hamza,

one otiose.

Originally they stood for ayi or a'i or aʾi --

definitely for short vowels.

Both words are written in IPak with silent alif + yāʾ-hamza

in Q52 with alif-hamza + silent yāʾ.

Add to this alif as akkusativ marker (at the end), as question marker at the beginning, hāʾ (tāʾ marbūṭa) as femining marker

(plus wau as name marker at the end outside the qurʾān عمرو)

and common words like انا.

So, to call all letters "consonants", makes no sense.

To call the rasm "consonantal" is wrong.

Call it: skeleton,

letter skeleton,

basic letters,

skeletal text,

stroke,

drawing.

Unfortunately most academics repeat what their predecessors wrote,

they can't look for them*selves, don't mention thinking for them*selves --

whether female, male, trans*gender or non*binary.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Nairīzī

Mirza Aḥmad an-Nairīzī (ca. 1650–1747) is the last of the classical Iranian calligraher s. Informations are hard to find, because often und...

-

40 years ago Adrian Alan Brockett submitted his Ph.D. to the University of St.Andrews: Studies in Two Transmissions of the Qurʾān . Now...

-

There are several types of madd sign in the Qurʾān, in South Asian masāhif: madd al-muttasil for a longer lengthening of the vowel used...

-

Although it is often written that the King Fuʾād Edition fixed a somehow unclear text, and established the reading of Ḥafṣ according to ʿĀ...