The King Fuʾād Edition of the Ḥafṣ transmission of the Qurʾān is soon celebrating

its 100th anniversary ‒ that's what the Dominican Institute in Cairo (IDEO) says.

Actually Orientalists are doing it, the edition has nothing to do with the celebration.

It is not even there. The two Cairo institutions with functioning online catalogs ‒ IDEO and AUC

‒ do not have a copy. And the two institutions that might have one ‒ al-Azhar and

the National Library (Dar al-Kutub) ‒ have no online catalogue for the time being.

Fortuately, both the Prussian and the Bavarian Staatsbiblothek have

a copy of the original print of 1342/1924 (the Bavarian Academy of Sciences has another copy).

The French Biblothèque National (BnF) claimed to have five copies printed in 1919.

When I wrote them that this was impossible, they discovered that three of their catalog

entries refered to the same physical object and streamlined it to this:

Originaly they wrote that it was printed in

Al-Qāhiraẗ : al-Maṭbaʿaẗ al-Amīriyyaẗ, 1919

القاهرة : المطبعة الأميريّة, 1919

But in their copy one can read

المطبعة العربية ١١ شارع اللبودية درب الجماميز

Šārʿ Darb al-Ǧamāmīz connecting Bab al-Ḫalq (in the north-east) and es-Sayeda Zainab

(in the south-west) ‒ in the 1930s and '40s its southern part was named separetly

as Šārʿ al-Labūdīya ‒

definetly not in Būlāq, were the Government Press was located for 150 years before it was

transfered to Imbaba in 1972.

I don't know why the 1961 edition of the KFE was not printed in Būlāq,

but it seems to the case. My first idea, that the edition was not made by a government subsiduary, but a private

enterprise, is unlikely because the 1961 has not a continuous pagination (1-855), but three deparat one (2-827,

ا ب غ د ه و

, (1) ...(4))

When one reads IN the FRIST (and post '52) print(s)

that the print was accomplished by 7. Ḏulḥigga 1342 (= 10.7.1924),

this can not be the date of the publication. It can only be the day

when printing of the qurʾānic text was finished.

After that this note had to be set, the plates had to be made,

the gathering(s) with this note and the information that follow it

in the book had to be printed, all had to be made into a book block

and had to be bound (connected with the case).

By the time the book was published it was 1343/1925.

The cover of the first edition was

stamped ṭabʿat al-ḥukūma al-Miṣrīya sanat 1343 hiǧriyya.

Bibligraphicaly speaking, the date given on page [ص] can be used,

but in real life, the book was published only in the following year.

The Hounds of God and their handmaid did not know a thing about the King Fuʾād Edition, they even used

a picture from the 1952 edition to illustrate the 1924 one.

Okay, not everybody knows the 1924 Gizeh print has never been reprinted,

that the next edition was made in Būlāq on newly aquired machines with newly made plates

in a different formate and with changes in the back matter,

that the third edition had a word spelled differently,

but almost everybody not ignorant of all things qur'anic knows,

that the 1952 edition is a new edition ‒ different at 900 places.

Normally it is best to concentrate on the editions itselfs,

to scan them for differences, to read their backmatter carefuly,

but there are two texts on the 1924 edition worth studying:

Gotthelf Bergsträßer's "Koranlesung in Kairo" in Der Islam 20,1, (1932) pp. 1-42

and Abd al-Fattāḥ (ibn ʿAbd al-Ġanī) al-Qāḍī's Tārīḫ al-Muṣḥaf aš-Šarīf

(esp. pp. 59-66 in the 1952 edition by Maktabat al-Jundī).

Abd al-Fattāḥ al-Qāḍī writes of three editions:

al-Muḫallalātī's of 1308/1890

al-Ḥusainī al-Ḥaddād's of 1342/1924

aḍ-Ḍabbāġ's of 1371/1952 on which he participated as one of the editors.

Back to the copies at our disposale: IDEO has one from 1354/1935

the first edition can be found in Berlin, Munich (BsB and in the Academy of Sciences), Bonn,

Kiel, Basel, Zürich (UZH), Nijmegen, Leiden

the 1344/1925 edition in Münster, Berlin (FUB), Kiel

1346/1927/8 in Leiden, Tübingen, Freiburg

1347/1928/9 in Würzburg, Munich, Erlangen-N, Bayreuth, Hamburg, Halle, Berlin (HU), Greifswald, Bamberg, Gießen, Kiel, Wien, Kopenhagen, Provo UT (BYU),

1936 Beirut (USJ)

many have a copy of the NEW King Fuʾād Edition of 1952

Berlin has two from 1952, one from before the revolution mentioning King Fuʾād on page [alif],

one with the page and its empty verso thrown out

Jena, Erfurt, Göttingen, Hamburg, Bamberg, Erlangen-N, Marburg, Eichstätt, Bonn, Mannheim,

Munich (BSB & LMU) Stuttgart, Tübingen, Leiden, Freiburg, Stockholm, VicAlbert, Aix-Marseille, Madrid,

Edinburgh U, Oxford, Binghamton NY, Allegheny PA, Columbus (OSU)

The second edition (1344) was reprinted by Maṭbaʿa al-ʿarabiyya in the 1930s, by the Chinese Muslim Society in Bakīn 1955 (without the page mentioning the king and with chinized graphics and probably by Maktabat al-Šarq al-Islāmiyya wa-Maṭbaʻatuhā in 1357/1938 ‒ I say "probably" because it could be a reproduction of the third or even later edition.

In 1938 the Nizam of Hyderabad had the text set with sorts he had bought from Būlāq, it was printed in two volumes along Pickthall's English translation in two volumes

and reprinted by Gaddafi's Islamic Call Society ‒ plus a French version alongside D.Masson's translation.

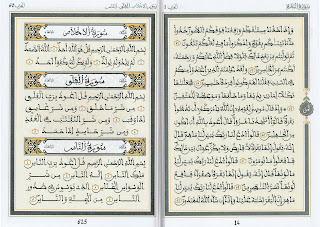

The 1952 edition, aḍ-Ḍabbāġ's edition, was reprinted a lot:

1379/1960 in Taškent/Ṭašqend

in Bairut/Damascus often mostly with an added ن in 73:20 (one of these was reprinted in ʿAmmān and made it

into the web archive

There were reproduction on less than 827 pages: the 1952 edition was photographed 1:1, the film was

cut and rearranged on a light table. Instead of 12 lines per page, we get 14 or 15 longer lines,

1983 in Qaṭar and in Germany. The German edition was made together with the Islamic Text Society (ITS), Cambridge.

Since its ISBN is a German one, I guess, the publishing place is Stuttgart, not Cambridge or London.

There were three editions: big and medium size leather bound, and a big one in cloth.

The qurʾānic text is a reprint of the 1952 al-Amīriyya edition,

the back matter was freshly set (not as neat as the original ‒ a pity!

As a rule, 827 page editions without title page are by the Government Press,

those with a title page are by private or non-Egyptian publishers ‒

the Frommann-Holzboog/ITS is the only non-Amīriyya one without title page,

no titel on the cover, nor the spine.

The text of 1952 was published by the Government Press after 1976 for about ten years

freshly set on 525 pages in several formats: with plastic cover, cartboard, leather, small, medium and large ‒ quite a success for a decade ‒ the last reprint was 1988 in Qaṭar.

And then came ʿUṯmān Ṭaha on 604 pages ‒ first with 100% the same text, later with different spelling at 2:72 and 73:20 and (most ? all ?) lāʾ pauses gone.

Tuesday, 12 October 2021

Thursday, 22 July 2021

Asmāʾ Ḥilālī

Asmāʾ Ḥilālī:

Asmāʾ Ḥilālī:

Despite the proliferation of scholarly editions of old Qurʾānic manuscriptsWhat can this mean?

over the last twenty years,

the popularity of the Cairo edition of the Qurʾān has never been challenged.

What is the connection between scholarly editions of qurʾānic fragments and

the ‒ supposed! ‒ popularity of the King Fuʾād Edition of the qurʾān,

called by her "the Cairo edition,"

which on its own shows that she is weak on logic.

Since there are more than a thousand Cairo editions of the qurʾān,

to call a particular one "THE Cairo edition" (TCE)

betrays madness ‒ unless one assumes that she ignores

the function of the definite article.

It's like:

Despite the proliferation of suburban gardensor

the popularity of the Amazonas forest has not declined.

Despite the popularity of Maradona and Rinaldo

the greatness of Maria Callas is unchallenged.

The use of TCE instead of the many good (or less good) names for

the Gizeh print,

the 1924 Amīriyya edition,

the 1924 King Fuʾād edition,

the Amīri edition = here s.o. did not see that Amīriyya is short for al-maṭbaʿa

al-amīriyya, thought that it refered to King Fuʾād ‒>

corrected it to amīrī, because the King is not a Queen

the 1924 muṣḥaf al-mesāḥa

the Government print, der amtliche ägyptische ...

the 12 liner (مصحف ١٢ سطر) of 1924

shows that Asma Hilali did not know a thing about the Egyptian Government

Edition of 1924/5 at the time of writing the "Call for proposals".

TCE is a recent coinage by non-English speakers.

The Gizeh print is the ONLY muṣḥaf ever printed in Gizeh proper.

Only the 827plus page editions ‒ without titel page, but more than twenty pages AFTER the qurʾānic text ‒ by the Amīriyya (1924-1975) have 12 lines,

but they are not all the same: the 1952 edition is quite different from the 1924 one:

(and the second and third edition have a few changes NOT included in the 1952 edition)

about 900 differences between 1924/5 and 1952!

During the conference Asma Hilali was the only one who spoke of "muṣḥaf al-Qāhira" (Omar Hamdan spoke of al-Qāhira-print, most spoke of "muṣḥaf al-malik Fuʾād") ignoring that the Amīriyya never refers to al-Qāhira, but to Miṣr, Būlāq, and Gizā.

Before 1920 all private publishers were situated south-west of al-Azhar, late comers were situated in al-Faggāla St.

Sunday, 11 July 2021

(partial) Assimilation

Two words from 2:8 according to five orthographic standards, all Ḥafṣ, all pronounced the same.

The top one (King Fuʾād Edition) and the bottom one (Ṭabʿo Našr, Iran) look similar, but are radically different -- because the Centre for Print and Distribution abolished the sukūn-sign: so in the bottom the nūn has an (unwritten) sukūn and the qāf has an unwritten long /ū/

-- just has the Turkish line just above).

In the top line the nūn has no sukūn, which means in that orthography: do not pronounce as /n/, but say /mai/.

The same phenomenon (partial assimilation) is written in Hind/Hindustan/India+Pakistan+BanglaDesh (third from below) and

Standar Indonesia (2.-4. line)

by sukūn above the nūn (which means according to that orthography: NOT silent) plus šadda above the yāʾ (hence prounced at the end of the first AND the beginning of the second word: mai yaqūl).

In Turkey

and Iran (complete and partial) assimilation is not written.

Sunday, 30 May 2021

The Pope, The Cairo Edition

Among Catholics one may speak of "the pope", among "normal" people one SHOULD say "the Roman pope", "the pope of the Occident", "the bishop of Rome", because ‒ leaving metaphorical use aside ‒ there are two more popes: the Coptic and the Greek "bishof of Alexandria and all Africa" in Cairo ((the bishops of Antiochia and All the Orient are not styled as pope)). What is common knowledge among Egyptian Christians is unknown to many people in the States or in the UK.

Unlike popes, of which there are only three at a time, there are literaly thousand Cairo editions of the qurʾān. But some young scholars write of "The Cairo Edition". Out of ignorance or stupitity? Maybe they do not know the difference between "a" and "the" ... When I alerted one, s/he added "colloquially known", an other just shrugged h*r/s shoulders, a third admitted that s/he has never looked into another muṣḥaf ‒ although as Professor of Islamic Studies s/he should have been to a mosque and/or an islamic bookshop and opened a muṣḥaf used by local Muslims (and they certainly do NOT use the KFE/King Fuʾād Edition = idiot's "CE"!)

Sometimes one sees "the St. Petersburg edition of the Qurʾān". I do not know how many editions exist ‒ certainly not just one: First we know of editions in 1787, 1789, 1790, 1793, 1796 and 1798. Copies of these six editions have no year on the title page or in the backmatter ... ... so one could treat them as one: the 1787-98 Mollah Ismaʿīl ʿOsman St. Petersburg edition: Because there are more, like the 1316/1898 Muṣṭafā Naẓīf Qadirġalī St. Petersburg edition Note the title: Kalām Qadīm

which does not refer to an antique shop, to antiquarian,

but to the pre-existence of the kalāmullāh ὁ λόγος "THE St.Petersburg" edition is illogical. Only ignorant or stupid people use that expression. (Of course some are ignorant, stupid AND amoral.))

Unlike popes, of which there are only three at a time, there are literaly thousand Cairo editions of the qurʾān. But some young scholars write of "The Cairo Edition". Out of ignorance or stupitity? Maybe they do not know the difference between "a" and "the" ... When I alerted one, s/he added "colloquially known", an other just shrugged h*r/s shoulders, a third admitted that s/he has never looked into another muṣḥaf ‒ although as Professor of Islamic Studies s/he should have been to a mosque and/or an islamic bookshop and opened a muṣḥaf used by local Muslims (and they certainly do NOT use the KFE/King Fuʾād Edition = idiot's "CE"!)

Sometimes one sees "the St. Petersburg edition of the Qurʾān". I do not know how many editions exist ‒ certainly not just one: First we know of editions in 1787, 1789, 1790, 1793, 1796 and 1798. Copies of these six editions have no year on the title page or in the backmatter ... ... so one could treat them as one: the 1787-98 Mollah Ismaʿīl ʿOsman St. Petersburg edition: Because there are more, like the 1316/1898 Muṣṭafā Naẓīf Qadirġalī St. Petersburg edition Note the title: Kalām Qadīm

which does not refer to an antique shop, to antiquarian,

but to the pre-existence of the kalāmullāh ὁ λόγος "THE St.Petersburg" edition is illogical. Only ignorant or stupid people use that expression. (Of course some are ignorant, stupid AND amoral.))

Wednesday, 26 May 2021

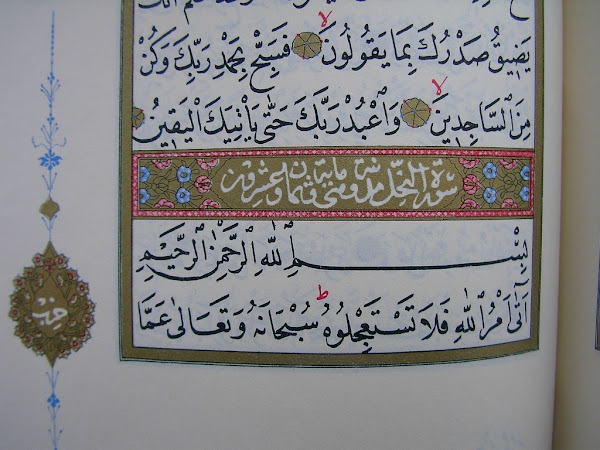

Giza 1924 ‒ better ‒ worse

The Egyptian Goverment Edition printed in Gizeh in 1924

was the first offset printed mushaf,

It was type set (not type printed).

It used smaller subset of the Amiriyya font not because the Amiriyya laked the technical possibility for more elaborate ligatures,

((in 1881 when they printed a muṣḥaf for the first time,

they used 900 different sorts, in 1906 they reduced it to about 400,

which they used in the backmatter of the 1924 muṣḥaf, in the qurʾānic text even less))

but to make the qurʾānic text easier to read for state school educated (wo-)men.

They did not want that the words "climb" at the end of the line for lack of space,

nor that some letter are above following letters.

It is elegant how the word continues above to the right of the baseline waw, but it is against the rational mind of the 20th century: everything must be right to left!

The kind of elegance you have with "bi-ḥamdi rabbika" is not valued by modern intelectuals. Here you see on the right /fī/, on the left /fĭ/, a distinction gone in 1924: And here you see, with which vowel the alif-waṣl has to be read ‒

something not shown in the KFE.

In Morocco they always show with which vowel one has to start (here twice fatḥa), IF one starts although the first letter is alif-waṣl, the linking alif, with is normaly silent.

In Persia and in Turkey one shows the vowel only after a pause, like here:

Both in the second and third line an alif waṣl comes after "laziM", a necessary pause, so there is a vowel sign between the usual waṣl and the alif ‒ a reading help missing in Gizeh 1924.

It was type set (not type printed).

It used smaller subset of the Amiriyya font not because the Amiriyya laked the technical possibility for more elaborate ligatures,

((in 1881 when they printed a muṣḥaf for the first time,

they used 900 different sorts, in 1906 they reduced it to about 400,

which they used in the backmatter of the 1924 muṣḥaf, in the qurʾānic text even less))

but to make the qurʾānic text easier to read for state school educated (wo-)men.

They did not want that the words "climb" at the end of the line for lack of space,

nor that some letter are above following letters.

It is elegant how the word continues above to the right of the baseline waw, but it is against the rational mind of the 20th century: everything must be right to left!

The kind of elegance you have with "bi-ḥamdi rabbika" is not valued by modern intelectuals. Here you see on the right /fī/, on the left /fĭ/, a distinction gone in 1924: And here you see, with which vowel the alif-waṣl has to be read ‒

something not shown in the KFE.

In Morocco they always show with which vowel one has to start (here twice fatḥa), IF one starts although the first letter is alif-waṣl, the linking alif, with is normaly silent.

In Persia and in Turkey one shows the vowel only after a pause, like here:

Both in the second and third line an alif waṣl comes after "laziM", a necessary pause, so there is a vowel sign between the usual waṣl and the alif ‒ a reading help missing in Gizeh 1924.

nūn quṭnī نون قطني nūn ṣila نون صلة

In Ḥafṣ ʿan ʿĀṣim there are about fifty places

where alif waṣl followes tanwin

linked with kasra /ini/.Asia writes a small(quṭnī) nūn.

Here a Persian last page (with wa- at the end of line 1 it can only be from a farsiphone enviroment). After the first verse there is "la": no need to stop; if one stops, the first word of verse 2 has a hamza-fatha ‒ although the word is normally written with alif-waṣla. But WHEN/IF one joins, it becomes /ʾaḥaduni-llāh/ ‒ note the hamza-fatha on /ʾaḥadun/. Muḥammad Ṣadīq al-Minšāwī recites it both ways.

Tuesday, 25 May 2021

al-Wāqiʿa 2 / kāḏība

In Baqara 72 I showed that "Medina" makes undocumented changes to Būlāq52.

Here I show that Qaṭar made another change to Būlāq52 ‒ again without explanations. The Iranian Center for Printing and Distributing the Qurʾān (Ṭabʿo Našr) developed a new rasm, a new orthography and new vowelled waṣl signs. After studying the literature on writing the muṣḥaf and 26 important maṣāḥif from different regions and different riwāyāt, they publish their results and their reasons.

In Indonesian there was a commitee of ʿulema from all over the country that deliberates 1974 to 1983 and fixed a standard, a second comittee revisted the standard in 2002, and a third from 2015 to 2018.

Here I show that Qaṭar made another change to Būlāq52 ‒ again without explanations. The Iranian Center for Printing and Distributing the Qurʾān (Ṭabʿo Našr) developed a new rasm, a new orthography and new vowelled waṣl signs. After studying the literature on writing the muṣḥaf and 26 important maṣāḥif from different regions and different riwāyāt, they publish their results and their reasons.

In Indonesian there was a commitee of ʿulema from all over the country that deliberates 1974 to 1983 and fixed a standard, a second comittee revisted the standard in 2002, and a third from 2015 to 2018.

Sunday, 23 May 2021

Morocco ... Muṣḥaf al-Muḥammadī

To commemorate Hassan II's silver jubilee and later Muhammads VI's accession to the throne the Kingdom

published editions in maghrebian style ‒ both in colour and back&white.

I looked in vain for information about the printing place.

This could be the reason the reserve::  The press wasn't in the Sherifian Kingdom, but in Cairo. Al-Muǧallad al-ʿArabi (often printers make up names for special occasions) was in charge.But the third edition was home made ‒ in a press founded in Faḍāla (named Muhammedia since 1959) after WWII and bought in the 1960ies by the Minstery for Religious Affairs and Pious Foundations al-Maṭbaʿ al-Faḍāla.

The press wasn't in the Sherifian Kingdom, but in Cairo. Al-Muǧallad al-ʿArabi (often printers make up names for special occasions) was in charge.But the third edition was home made ‒ in a press founded in Faḍāla (named Muhammedia since 1959) after WWII and bought in the 1960ies by the Minstery for Religious Affairs and Pious Foundations al-Maṭbaʿ al-Faḍāla.

While under Hassan II there was only one Royal Muṣḥaf (in cheap and in expensive editions) ‒ written by seven Moroccan calligraphers

While under Hassan II there was only one Royal Muṣḥaf (in cheap and in expensive editions) ‒ written by seven Moroccan calligraphers

there are new four different ones:

‒ one hand written, similar to his father's

there are new four different ones:

‒ one hand written, similar to his father's ‒ one computer set ‒ "andalusian", i.e. with green dots for hamzat,

‒ one computer set ‒ "moroccan"and the same in an expensive edition:

and with reduced colours:

‒ one with images of wooden tablets from madrasas‒ printed 2007 in Graz, Austria.

‒ one computer set ‒ "andalusian", i.e. with green dots for hamzat,

‒ one computer set ‒ "moroccan"and the same in an expensive edition:

and with reduced colours:

‒ one with images of wooden tablets from madrasas‒ printed 2007 in Graz, Austria.

The press wasn't in the Sherifian Kingdom, but in Cairo. Al-Muǧallad al-ʿArabi (often printers make up names for special occasions) was in charge.But the third edition was home made ‒ in a press founded in Faḍāla (named Muhammedia since 1959) after WWII and bought in the 1960ies by the Minstery for Religious Affairs and Pious Foundations al-Maṭbaʿ al-Faḍāla.

The press wasn't in the Sherifian Kingdom, but in Cairo. Al-Muǧallad al-ʿArabi (often printers make up names for special occasions) was in charge.But the third edition was home made ‒ in a press founded in Faḍāla (named Muhammedia since 1959) after WWII and bought in the 1960ies by the Minstery for Religious Affairs and Pious Foundations al-Maṭbaʿ al-Faḍāla.

While under Hassan II there was only one Royal Muṣḥaf (in cheap and in expensive editions) ‒ written by seven Moroccan calligraphers

While under Hassan II there was only one Royal Muṣḥaf (in cheap and in expensive editions) ‒ written by seven Moroccan calligraphers

there are new four different ones:

‒ one hand written, similar to his father's

there are new four different ones:

‒ one hand written, similar to his father's ‒ one computer set ‒ "andalusian", i.e. with green dots for hamzat,

‒ one computer set ‒ "moroccan"and the same in an expensive edition:

and with reduced colours:

‒ one with images of wooden tablets from madrasas‒ printed 2007 in Graz, Austria.

‒ one computer set ‒ "andalusian", i.e. with green dots for hamzat,

‒ one computer set ‒ "moroccan"and the same in an expensive edition:

and with reduced colours:

‒ one with images of wooden tablets from madrasas‒ printed 2007 in Graz, Austria.

Saturday, 22 May 2021

Taj Compagny Ltd editions

The most important publisher of maṣāḥif world wide is the Taj Compagny Ltd.

It was founded 1929 in Lahore. They expanded to Bombay and Delhi. After partition the main office was in Karachi, later offices in Rawalpindi and Dhakka were added. As you can see below Peshawar was another publishing place.

They published maṣāḥif with nine, ten, eleven, twelve, 13, 16, 17 and 18 lines. 848 pages with 13 lines of qurʾānic text plus 14 pages prayers and explanation became the South African standard. Another muṣḥaf with 13 lines has 747+4 pages, an other one has 15 lines (611 berkenar pages) ...

They were reprinted from Kashgar to Johannisburg,

the one on 611 pages with 15 lines was reprinded by many publishers around the world, from Delhi to Medina (starting in 1989)

... 16 lines (both with 485 pages of q.text, and with 549 of q.text plus additional ten pages), with 17 lines per page (489+4 pages), 18 lines (486+3 pages), plus many bilingual editions.

Inside Pakistan they were copied indirectely: Many publishers had calligraphers rewrite editions with exactely the same page layout, line by line copied. Philipp Buckmayr found in article by Mofakhkhar Hussain Khan published in Bangla Desh, stating that the maṣāḥif of Taj and of FerozSons, Lahore were calligraphed by ʿAbdur-Raḥmān Kilānī (1923-1995). Although tremendiously influencial, they had no commerical success. Twice they went bankrupt. In 1980 and in 2004 "Taj Compagny Ltd" was refounded.

Besides systemic differences to the "African" way (long vowel signs, nūn quṭnī, no leading hamza sign but alif as hamza für /ʾā, ʾī, ʾū/, ḥizb = quarter juz <not half>) there are a couple of silent alifs in the "Asian" tradition (but even by one publisher not consistent, but all allowed):

For 5:29 and 7:103 I added early examples from Lucknow prints. zwei Nachträge: Philipp Bruckmayr verweist auf Mofakhkhar Hussain Khan (The Holy Qurʾān in South Asia: A Bio-Bibliographic Study of Translations of the Holy Qurʾān in 23 South Asian Languages, Dhaka, Bibi Akhtar Prakãšanî, 2001), dem zufolge Kilānī den 15Zeiler (und wohl auch andere) geschrieben habe. Da Khan nicht in Lahore wohnt, sondern in Ostbengalen, gebe ich das indirekt wieder. Ob es tatsächlich so ist, weuiß ich nicht. Hier eine Schmuckausgabe: these days:

It was founded 1929 in Lahore. They expanded to Bombay and Delhi. After partition the main office was in Karachi, later offices in Rawalpindi and Dhakka were added. As you can see below Peshawar was another publishing place.

They published maṣāḥif with nine, ten, eleven, twelve, 13, 16, 17 and 18 lines. 848 pages with 13 lines of qurʾānic text plus 14 pages prayers and explanation became the South African standard. Another muṣḥaf with 13 lines has 747+4 pages, an other one has 15 lines (611 berkenar pages) ...

They were reprinted from Kashgar to Johannisburg,

the one on 611 pages with 15 lines was reprinded by many publishers around the world, from Delhi to Medina (starting in 1989)

... 16 lines (both with 485 pages of q.text, and with 549 of q.text plus additional ten pages), with 17 lines per page (489+4 pages), 18 lines (486+3 pages), plus many bilingual editions.

Inside Pakistan they were copied indirectely: Many publishers had calligraphers rewrite editions with exactely the same page layout, line by line copied. Philipp Buckmayr found in article by Mofakhkhar Hussain Khan published in Bangla Desh, stating that the maṣāḥif of Taj and of FerozSons, Lahore were calligraphed by ʿAbdur-Raḥmān Kilānī (1923-1995). Although tremendiously influencial, they had no commerical success. Twice they went bankrupt. In 1980 and in 2004 "Taj Compagny Ltd" was refounded.

Besides systemic differences to the "African" way (long vowel signs, nūn quṭnī, no leading hamza sign but alif as hamza für /ʾā, ʾī, ʾū/, ḥizb = quarter juz <not half>) there are a couple of silent alifs in the "Asian" tradition (but even by one publisher not consistent, but all allowed):

For 5:29 and 7:103 I added early examples from Lucknow prints. zwei Nachträge: Philipp Bruckmayr verweist auf Mofakhkhar Hussain Khan (The Holy Qurʾān in South Asia: A Bio-Bibliographic Study of Translations of the Holy Qurʾān in 23 South Asian Languages, Dhaka, Bibi Akhtar Prakãšanî, 2001), dem zufolge Kilānī den 15Zeiler (und wohl auch andere) geschrieben habe. Da Khan nicht in Lahore wohnt, sondern in Ostbengalen, gebe ich das indirekt wieder. Ob es tatsächlich so ist, weuiß ich nicht. Hier eine Schmuckausgabe: these days:

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Merkaz Ṭab-o Našr

from a German blog coPilot made this Englsih one Iranian Qur'an Orthography: Editorial Principles and Variants The Iranian مرکز...

-

There are two editions of the King Fuʾād Edition with different qurʾānic text. There are some differences in the pages after the qurʾānic t...

-

there is no standard copy of the qurʾān. There are 14 readings (seven recognized by all, three more, and four (or five) of contested status...

-

Although it is often written that the King Fuʾād Edition fixed a somehow unclear text, and established the reading of Ḥafṣ according to ʿĀ...