knows nothing about the history of printed maṣāḥif,

but she writes about it:

the mushaf, i.e. the text put onto sheets, bound between two covers, was transmitted through the centuries, generation by generation ... to end up in the last century, in 1925, in the form of a printed textI fail to understand, what Neuwirth wants to say.

A. Neuwirth, Der Koran als Text der Spätantike, Berlin: Suhrkamp 2010. p. 190

Does she ignore that the Qur’an was printed in 1537, in 1694, in 1698, in 1787 for the first time by Muslims in St. Petersburg, in 1834 in Leipzig, in the 1830s ten different prints in Persia and India?

Does she ignore that from 1875 each year thousands were printed in Istanbul and India?

What does she mean by "end up in the form of a printed text"?

What does she want to say by "transmitted generation by generation"?

Okay, before sound could be recorded, the oral text had to be taught from teacher to pupil:

it was indeed transmitted through the ages.

But was that necessary for the muṣḥaf?

Was it not possible to read (and copy) a muṣḥaf written by a person dead at the time of reading the manuscript?

It was not common to give an isnād of scribes who each have learned the art of writing a muṣḥaf from an older scribe/ ḫaṭṭāṭ.

When we believe the main editor of the King Fuʾād Edition it was a reconstruction,

based on the oral text and Andalusian books from the 11th and 14th century on the orthography of the qurʾān.

I believe it was an adaptation of a printed copy of the transmission Warš to the normal Egyptian reading of Ḥafṣ.

For sure, it was not the last in a chain of transmitted maṣāḥif, from Egyptian scribe to pupil (through the generations).

Neuwirth has never seen the King Fuad Edition.

Consistently she cites it wrongly.

The book has no title on the cover, no title page; the first page is empty,

the first page with something on it, has the Fatiḥa.

In the afterword, it refers to itself as "al-muṣḥaf aš-šarīf,"

in the dedication to King Fuʾād it calls itself "al-muṣḥaf al-karīm".

Because it has no title, according to the German library rules,

the given/ assumed/ generic title is in brackets: "[qurʾān]",

but Neuwirth gives two different one in the notes:

„Al-Qur‘ân al-Karîm, Kairo 1925“ (Der Koran als Text der Spätantike, p. 30)

and „Qur‘ân karîm 1344/1925“ (Der Koran als Text der Spätantike,. p. 273).

Neuwirth has never read the information/ تعريف at the back of the King Fuʾād Edition,

nor read and understood the article Gotthelf Bergsträßer wrote about it.

Otherwise, she would know that the editors claim to have reconstructed the muṣḥaf from scratch.

The chief editor is not a scribe, but the chief reader/ qāri of Egypt: he knows the qurʾān by heart ‒ in seven to twenty transmissions.

In the تعريف he states that he has transcribed the oral text according to a didactic poem based on two medieval books on the basic letters for writing the qurʾān,

on a Maghrebian book on vowelling but with Eastern vowel signs and other books ...

I interrupt, because I do not believe, what is written in the تعريف

I am convinced that the editor took a Warš muṣḥaf and adopted it to Ḥafṣ.

For the vowelling, he did not have to replace Maghrebian signs by Eastern signs because the system developed by Al-Ḫālil ibn Aḥmad al-Farāhīdī was current in the West because printing colour dots was too complicated/ expensive at the time.

The "information" further informs us that verse numbering and liturgical divisions are according to a recent Egyptian scholar, Abū ʿĪd Riḍwān ibn Muḥammad ibn Sulaimān al-Muḫallalātī, again not informing us that they adopted the Moroccan system in which a ḥizb is half a ǧuz ‒ not a quarter as before, as in Turkey, Persia, India, Nusantara.

There are many more things, in which Egyptian maṣāḥif used to be like Ottoman, Persian, Indian and Indonesian maṣāḥif,

in which from now on they are like Moroccan ones ‒ without giving an authority to whom the King Fuʾād Edition is said to adhere.

—> The KFE just follows Maghrebian maṣāḥif, a switch of tradition, the opposite of what Neuwirth wrote, the opposite of what Bergsträßer believed.

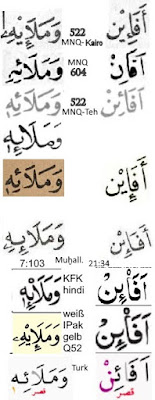

The KFE has three different forms of tanwīn, and three different forms of sukūn ‒ to be precise: the Moroccan sukūn for "unpronounced" (circle or oval) and the Indian sign for "unvowelled" (clearly the first letter of ǧazm without the dot not "ḫa without the dot" as they write).

Egyptian prints used to have signs for long vowels, now they have the Maghrebian system, in which a vowel sign AND a vowel letter (ḥarf al-madd) is needed (hence a small letter is added whenever necessary).

When a word starts with /ʾā/ they used to write the letter hamza (i.e. an alif) + a turned fatḥa,

now they copy the Maghrebian practice:

seatless hamza-sign+fatḥa followed by a lengthening alif.

This does not change the rasm, it is not mentioned in the scholarly literature cited.

Vowelless nūn not followed by h,ḥ,ḫ,ʾ,ʿ,ġ used to have a sukūn (as in Osm, Soltani, IPak), now they have nothing because they are not pronounced (clearly as themselves - not iẓhār) because they are (partly) assimilated or reduced.

compare the beginning of al-Baqara from Bombay vs. Medina (aka IPak vs. Q52):

There used to be two (or three) different madd signs, now there is just one.

In all these things the King Fuʾād Edition clearly copies Maġribi Warṣ muṣāḥif ‒ unlike pauses, numbering, rasm, dotting they are not described in books ON the matter, al-Ḥaddad could only copy them from maṣāḥif. Strangely neither Bergsträßer, nor anyone else noticed that.

And there is more: no more sign for Baṣrī numbers, no more small nūns, when tanwīn before alif is spoken as a/u/i-ni (called "ṣila nūn" or on the subcontinent "quṭnī nūn"/tiny nūn).

To summarize:

Except for the transmission of Ḥafṣ, the Kufī numbering, and a new pause system (based on Saǧāwandī), and the letter font of the Amiriyya (by Muḥammad Ǧʿafar Bey)

this is Maghribian.

That the rasm was not ad-Dānī, not al-Ḫarrāz was clear. When people found out that it was only 95% Ibn Naǧāḥ, the editors in Medina and in Tunis added "mostly" (ġāliban / fĭ l-ġālib) to the information at the end of the book. Since it is 99% Maghribian, I guess al-Ḥaddād just adopted an existing muṣḥaf ‒ the "reconstruction" is a myth.

The other great German qurʾān expert, Hartmut Bobzin, gives the right year, he writes:

the publication of the so-called "Azhar Koran" on 10 July 1924 (7.Dhū l-hiǧǧa 1342 in the Islamic calendar)which is not correct either: on that day the printing was finished,

FROM VENICE TO CAIRO: ON THE HISTORY OF ARABIC EDITIONS OF THE KORAN (16th ‒ early 20th century), in Middle Eastern Languages and the Print Revolution A cross-cultural encounter. Westhofen: WVA-Verlag Skulima 2002. p.171

before the book could be published it had to be bound.

One can be a good translator of the qurʾān, without knowing a thing about publishing,

but maybe it is not a good idea to write about publishing without knowing a thing about it.

And the King Fuʾād Edition is not the Azhar-Koran, nor known as such.

It was produced by the Government Press under the direction of the Chief Qārī of Egypt, assisted by men from the Education Ministry and the Pedagogical College on Qaṣr al-ʿAinī.

In the end, the chief of al-Azhar and the chief copy editor of the Government Press vouched for correctness.

Only 1977 to 1987, an "Azhar Koran" was printed ‒ in five different sizes, different bindings and get-ups (with two reprints in Qaṭar, the last one in 1988)

Everything Bobzin writes is completly wrong

Der "Azhar-Koran" löste eine wahre Flut gedruckter Koranausgaben in allen islamischen Ländern aus, da man sich nun für den Korantext auf eine anerkannte Autorität stützen konnte.

The "Azhar Koran" prompted a veritable flood of printed editions of the Koran throughout the Islamic world, as there was now a recognized authority on which the Koran text could be based. ibidem

Die Entscheidung der Kairiner Gelehrten für den Text nach der Lesart "Hafs 'an 'Asim" verschaffte ihr nunmehr gegenüber allen anderen Lesarten einen entscheidenden Vorteil.That Ḥafṣ experienced an upsurge due to the KFE is nonsense. Only in the Sudan it gained a bit ‒ but only because it is closer to the Arabic taught in state schools (which had more pupils now).

there was a pronounced tendency to understand the "Azhar Koran" as virtually a "textus receptus", in other words as the only binding Koran text. The decision by the scholars in Cairo in favour of the text in the "Hafs 'an 'Asim" version secured it a decisive advantage over all other versions. ibidem

Allen "modernen" Koranausgaben bleibt eine Gemeinsamkeit ..., daß für die Herstellung des Satzes keine beweglichen Lettern verwendet werden, sondern stets ein kalligraphisch gestalteter Text zugrunde liegt, der entweder lithographisch oder photomechanisch vervielfältigt wird.Untrue: KFE'24, Kabul'34, Hyderabad'38 and the Muṣḥaf Azhar aš-Šarīf are type set.

all the "modern" editions of the Koran still have one thing in common ... above all in the fact that no movable type is used to set the pages, which are, instead, always based on a

calligraphically designed text which is reproduced either by lithography or by photomechanical processes.

Im Hinblick auf den Text folgte [Flügel] nicht einer einzigen Lesart, sondern bot einen Mischtext (wie das übrigens in den meisten Handschriften der Fall ist).Again, Bobzin states a fact ("most manuscript editions are a mix of readings") without proving it. It would be interesting to get information about one or two, not to mention "most" manuscripts mixing readings!

As regards the text itself he did not adhere to a single reading, but instead provided a mixed text (as was the case in most manuscripts). p.169

In the meantime, young brilliant scholars have surpassed Neuwirth and Bobzin in writing nonsense. Although there are more than a thousand editions printed in Cairo, they call the first (and for over fifty years: the only) Gizeh print "the Cairo Edition (CE)". It is as calling Notre-Dame de Paris "the Paris Novel (PN)."

‒