Wednesday, 12 June 2024

Tuesday, 11 June 2024

Tehran 1827 (+ 1831)

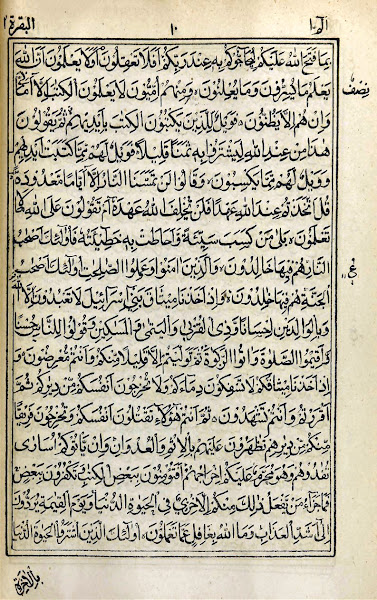

Here images from the first Persian type set mushaf.

... and an illustration from a book by Borna Izadpanah:

... and three from a 1831 print set with the same types from Borna Izadpanah's twitter account (the Royal Asiatic Society holds it). First a page with the beginning of sura XV ‒ note that there is empty space for a colour title box.

here 2:138 and the next verse

last a fake: in the first line I have moved a turned kasra /ī/ from under yāʾ forward under its letter. In the second line 2:15 is interesting because /ʾallāh/ HERE gets a fatha (which includes a hamza) because of the pause before it:

‒

Sunday, 9 June 2024

e.Conidi II

Emanuela Conidi just informed me that Geoffrey Roper was her source.

Maybe I am too strict, but this book should be burned as a act of faith.

THE BOOK. A GLOBAL HISTORY is less than useless <-- it has no notes,

no proper (i.e. checkable) sources

The two pages on "printing the Qurʾān" (548-50) shine with inaccurancies:

in the 1830s ... the distribution of copies was successfully blocked [in Egypt] by the religious authoritiesmaybe, but without sources: useless

in the 1850s, some were distributed, but only after each individual copy had been read by a Qur’anic scholar and checked for errors, at great expense.Does Roper really think that Muslims (because they are Muslims?) are so stupid that they do not understand, that they do not have to check "each individual copy" because they are identical????

the Ottoman calligrapher and court chamberlain Osman Zeki Bey (d. 1888) started printing Qur’āns reproducing the handwriting of the famous 17th-century calligrapher Hafız OsmanAccording to my sources Osman Zeki Bey died 1890, and he did print maṣāḥif by the 19th century Hafiz Osman, not by the earlier namesake. And more important: the first reproduction of a muṣḥaf was one penned by Şekerzade Mehmed Efendi (d. 1166/1753) not by any of the Osmans, whose maṣāḥif were often reproduced later.

(i.e. the form of the text as it appears in the early MSS without vocalization and diacritics)wrong again: there is not a single very early MSS without voacalization and diacritics

The lead was taken by scholars at Al-Azhar mosque-university ... After seventeen years of preparatory work, their edition was published in 1924, under the auspices of King Fu’ād of Egypt. It was printed orthographicallythe lead was taken by directors in the Ministry of Education, they and people from the Government Press decided on the form, the text given to the type setters had been written by the chief recitor of Egypt; that the text was not just a copy of the most popular muṣḥaf of the time, the 522-page-muṣḥaf written by Muṣṭafā Naẓīf, was due to the work done by Šaiḫ Muḫallalātī and the decision of al-Ḥusainī al-Ḥaddād to largely follow the Maghrebian model. ‒

Friday, 7 June 2024

gullible or sceptical

Although the title is "Reciting the Qurʾān in Cairo" ("Koranlesung in Kairo") the first part of G. Bergsträßer's

article in Der Islam XX (1932) is largely on the "official" Egyptian edition of the Qurʾān, der "amtliche", the Government edition,

the King Fuʾād Edition called the "12 liner (muṣḥaf 12 saṭr") by the book sellers or Muṣḥaf al-Amiriyya after the Government Press ((never

The Cairo Edition, nor the Azhar Qurʾān, and please not Mushaf Amiri/Royal Edition)) and about the chief recitor of the time and the one who followed him in that function (which Bergsträßer

did not know of course). The article is rich in information, both what the two men have told him and what is written in

the explanations (taʿrīf), the afterword of the book.

First Bergsträßer informs the reader on the 22 pages that follow the 827 pages of the qurʾānic text.

Then he tells us what is written in an advertising brochure/ leaflet (Prospekt); he uses the subjunctive mode of indirect speech

leaving it to the reader to believe what is written ‒ or not.

I do not believe one of the typewritten words.

طبعة الحكومية المصرّية

-- . --

١٣٤٣ هجرّية

سـنة

There were minor changes between 1343/1925 and 1347/1929 either in the quranic text or in the information that follows it, but there were no changes in 1936; there never was an Faruq (or Farūq) edition; until the revolution of 1952 all full editions of the qurʾān by the Government Press were dedicated to King Fuʾād. How comes that some youngster call the "King Fuʾād Edition" "The Cairo Edition" or "the Azhar Edition"? My guess: because they are so young, too young to have spent days in the book shops and publishers around the Azhar. From 1976 to 1985 the most common edition was the "muṣḥaf al-Azhar aš-šarīf" printed by the Amiriyya in many different format, big and small, cheap and expenisve ‒ all with the qurʾānic text on 525 pages with 15 lines and only three pause signs (not to be confused with the "muṣḥaf al-Azhar aš-šarīf" by the Azhar, which is a reprint of the 522 page muṣḥaf written by Muṣṭafa Naẓīf.) But these youngster do not know that there is an "Azhar edition" that came 50 years after the KFE saw the light of day. And "muṣḥaf al-Qāhira" was the huge manuscript attributed to ʿUṯmān kept at al-Ḥusainī Mosque north of al-Azhar. From 1880 to today there were more than a hundred editions produced in al-Qāhira, in an industial area nearby, around the main railway station and in Bulāq, no person aware of this could imagine "The Cairo edition", ‒

In recent times the government had to destroy many imported copies because of mistakes, notably 25 years ago sinking a whole load in the Nile.As no year is given, no information of the kind of mistakes, no information on the printer ("Ausland") nor the importer, nothing on whom paid an compensation for the capital destroyed to whom (how much?), I do not believe it. The are serveral kind of mistakes possible: ‒ those that are not mistakes at all, just different convention (like whether a leading unpronounced alif carries a head of ṣād as waṣl-sign or not, or some otiose letters ‒ see earlier posts) ‒ type errors, that can be remedied by including a "list of errors" or by correcting them by hand ‒ binding error: several copies lack a quire having another one twice, or quires in the wrong order. Copies with binding error can not be sold. That you have to destroy hundreds of copies, there must be so many mistakes that it is virtually impossible to correct them by hand. So far Bergstäßer just reports what was written in the brochure. Now he tells us what the šaiḫ al-maqāriʾ Muḥammad ʿAlī Ḫalaf al-Ḥusainī al-Ḥaddād told him, but here he does not use the subjunctive of indirect speech, he gives obvious ("natürlich") facts.

Quelle für den Konsonatentext sind natürlich nicht Koranhandschriften, sondern die Literatur über ihn; er ist also eine Rekonstruktion, das Ergebnis einer Umschreibung des üblichen Konsonantentextes Of course, the source for the consonant text are not manuscripts, but the literature about it; it is therefore a reconstruction, the result of a rewriting of the usual consonant textThe source given for the rasm is a didactic poem Maurid aẓ-ẓamʾān by al-Ḫarrāz based on Abū Dāʾūd Sulaimān ibn Naǧāḥ's ʿAqīla but the Indonesian Abdul Hakim ("Comparison of Rasm in Indonesian Standard Mushaf, Pakistan Mushaf and Medinan Mushaf: Analysis of word with the formulation of ḥażf al-ḥuruf" in Suhuf X,2 12.2017), the Iranian Center for Printing and Spreading the Quran and the scholars advising the Tunisian publisher Hanbal/Nous-Mêmes have checked the text (either all of it or "just" a tenth ‒ from different parts) and found out, that the text of the King Fuʾād Edition and the King Fahd Edition do not tally with the ʿAqīla. While the Muṣḥaf al-Jamāhīriyya follows ad-Dānī's Muqniʿ all the time and the Iranian Center and the Indonesian Committee publish lists with words where they follow which authority (or in the case of the Iranian center even apply a different logic) al-Ḥusainī al-Ḥaddād and the Medinese King Fahd Complex claimed (!) to follow Abū Dāʿūd. As this is clearly not the case "Medina" and "Tunis" inserted a word in the explanations: ġāliban or fil-ġālib (mostly) and a caveat "or other experts." So: the KFC admitts that they do NOT follow Abū Dāʾūd all the time. Al-Ḥusainī al-Ḥaddād had told Bergsträßer what the orientalist wanted to hear. All professional recitors in Egypt know the differences between Ḥafs, Warš and Qālūn by heart. Being the chief recitor and a Malikite, he knew Warš even better than most. So what he really did, he copied an Warš copy into a Ḥafs script ‒ largely Abu Dāʾūd, but not 100 %. So the KFE was not a revolution, just a switch from Asia to Africa: a "no" to the Ottomans, a "yes" to the Maġrib. As I have already said, I recomment an old text. Gabriel Said Reynolds writes rubbish:

The common belief that the Qur’an has a single, unambiguous reading ... is above all due to the terrific success of the standard Egyptian edition of the Qur’an, first published on July 10, 1924 (Dhu l-Hijja 7, 1342) in Cairo, an edition now widely seen as the official text of the Qur’an. ... Minor adjustments were subsequently made to this text in following editions, one published later in 1924 and another in 1936. The text released in 1936 became known as the Faruq edition in honor of the Egyptian king, Faruq (The Qur’an in Its Historical Context, London New York 2008. p. 2)All wrong. The King Fuʾād Edition was not published on July 10, 1924, but the printing of its qurʾānic text was finished on that day. It was really only published after the book was bound in the next year according to the embossed stamp on its first page ‒ or just the second run of the first edition was stamp like this (?).

طبعة الحكومية المصرّية

-- . --

١٣٤٣ هجرّية

سـنة

There were minor changes between 1343/1925 and 1347/1929 either in the quranic text or in the information that follows it, but there were no changes in 1936; there never was an Faruq (or Farūq) edition; until the revolution of 1952 all full editions of the qurʾān by the Government Press were dedicated to King Fuʾād. How comes that some youngster call the "King Fuʾād Edition" "The Cairo Edition" or "the Azhar Edition"? My guess: because they are so young, too young to have spent days in the book shops and publishers around the Azhar. From 1976 to 1985 the most common edition was the "muṣḥaf al-Azhar aš-šarīf" printed by the Amiriyya in many different format, big and small, cheap and expenisve ‒ all with the qurʾānic text on 525 pages with 15 lines and only three pause signs (not to be confused with the "muṣḥaf al-Azhar aš-šarīf" by the Azhar, which is a reprint of the 522 page muṣḥaf written by Muṣṭafa Naẓīf.) But these youngster do not know that there is an "Azhar edition" that came 50 years after the KFE saw the light of day. And "muṣḥaf al-Qāhira" was the huge manuscript attributed to ʿUṯmān kept at al-Ḥusainī Mosque north of al-Azhar. From 1880 to today there were more than a hundred editions produced in al-Qāhira, in an industial area nearby, around the main railway station and in Bulāq, no person aware of this could imagine "The Cairo edition", ‒

Thursday, 6 June 2024

E.Conidi on the KFE

In her thesis e.Conidi writes on the King Fuʾād Edition:

The seventeen years required by Egyptian scholars for the preparation of the Fuʾād Qurʾān, from 1907 to 1924, were necessary to ensure the correctness of the text in adherence to ‘the approved norms in terms of content and orthography’, which was an indispensable precondition for accepting the duplication of the sacred text. (Sabev, ‘Waiting for Godot’, 109.)there is no book Waiting for Godot by O.Sabev, and in his Waiting for Müteferrika there is nothing on the KFE, not on page 109, nor anywhere else. But in G.Bergsträßer's article Koranlesung in Kairo Part 1 he writes, that a typewritten leaflet claimed that the preparations (Vorbereitungen) started in 1907, that the text was set, checked, revised by the chief recitor ordered to do so by the Azhar (im Auftrag der Direktion der Azhar). That the plan was to have printing plates being made in Germany, but that the outbreak of war had made that impossible, therefore the book was printed in Giza. First, I do not see what Conidi writes, that seventeen years were necessary to establish a correct text (in Egypt the text could only be the reading of Ḥafs; its oral text is fixed for centuries, and whether one uses the letters defined by ad-Dānī ((as al-Muḫallalātī did in 1890 and much later editors in Lybia)) or the ones defined by his pupil Abu Daʾûd ((as common in Morocco)) is of minor importance -- as I see it, the chief recitor choose the letters used in the Moroccan prints just changing the very few letters special to the reading of Warsh; (BTW, Indonesian scholar work 1974-84 for there standard, but first they came from all over the country, while Egypt is rather dentralized, and they work on three standards at the time, among them a Braille standard, something completely new.) and I do not see what scholars were involved beside the chief recitor. Second, I do not understand what happened between 1907 and the outbreak of the war, and what happened between 1915 and 1924. It all does not make sense. As I see it: after November 1914 when Egypt ceased to be a province of the Ottoman empire and the (hitherto) Governor took the same title as his (erstwhile) overlord: sulṭān, Egypt wanted to have a copy of the qurʾān different from the Ottoman model. And Abū Mālik Ḥifnī Bey ibn Muḥammad ibn Ismaʿīl ibn Ḫalīl Nāṣif (16.12.1855‒25.2.1919) , responsible for state run schools, expressed the wish for a print easier to read for "his" secular students. While the students at religous madrasas were used to the calligraphic style of qurʾān manuscripts, the modern students were used to school book, novels and news papers. He wanted a print with a clear base line, and clear right-to-left, not top-to bottom as in elegant calligraphy. For all of this no lengthy deliberations were necessary.

Giza1924, KFE I

The Giza Qurʾān

‒ is not an Azhar Qurʾān

‒ did not trigger a wave of printings of Qurʾāns,

because there was finally a fixed, authorized text

‒ the King Fuʾād Edition was not immediately accepted by Sunnis and Shiites

‒ did not contribute significantly to the spread of the reading of Ḥafṣ,

it was neither published in 1923 nor on 10 July 1924.

But it drove the abysmally bad Gustav Flügel edition out of German study rooms,

‒ had an afterword by named editors,

‒ gave its sources,

‒ took over ‒ apart from the Kufic counting,

and the pause signs, which were based on Eastern sources

‒ the Maghrebi rasm (mostly/ġāliban) according to Abū Dāʾūd Ibn Naǧāḥ)

‒ the Maghrebi small fall back vowels for lengthening

‒ the Maghrebi subdivision of the thirtieths (but without eighth-ḥizb)

‒ the Maghrebi baseline hamzae before leading Alif (ءادم instead of اٰدم).

‒ the Maghrebi missspelling of /allāh/ as /allah/

‒ the Maghrebi spelling at the end of the sura, which assumes that the next sura is recited immediately afterwards (without Basmala): tanwin is modified accordingly.

‒ the Maghrebi distinction between three types of tanwin (one above the other, one after the other, with mīm)

‒ the Maghrebi absence of nūn quṭni.

‒ the Maghreb non-writing of vowel shortening

‒ the Maghrebī (and Indian) notation of assimilation

‒ the Maghrebī (and Indian) attraction of the hamza sign by kasra

in G24 the hamza is below the baseline ‒ in the Ottoman Empire (include Egypt) and Iran the hamza stays above the line

New was the differentiation of the Maghreb Sukūn into three characters:

‒ the ǧazm in the form of a ǧīm without a tail and without a dot for no vowels,

‒ the circle as sign: should always be ignored,

‒ the (ovale) zero for sign: should be ignored unless one pauses thereafter.

‒ plus the absence of any mute (unpronounced) character.

‒ word spacing,

‒ Baseline orientation and

‒ exact placement of diacritical dots and ḥarakāt.

It was also not the first "inner-Muslim Qurʾān print" (A.Neuwirth).

Neuwirth may know a lot about the Qurʾān, but she has no idea about Qurʾān prints,

since there have been many prints by Muslims since 1830, and very, very many since 1875

and Muslims were already heavily involved in the six St. Petersburg prints from 1787-98.

It was not a type print either, but - like all except Venice, Hamburg, Padua, Leipzig,

St. Petersburg, Kazan, one in Tehrān, two in Hooghli, two in Calcutta and one in Kanpur

- planographic printing, although no longer with a stone plate, but with a metal plate.

It was also not the first to declare to adhere to "the rasm al-ʿUṯmānī“.

Two title pages from Lucknow prints of 1870 and 1877.

In 1895 appeared in Būlāq a muṣḥaf in the ʿUthmani rasm, which perhaps meant "unvocalized."

Kitāb Tāj at-tafāsīr li-kalām al-malik al-kabīr taʼlīf Muḥammad ʿUthman ibn as-Saiyid

Muḥammad Abī Bakr ibn as-Saiyid ʻAbdAllāh al-Mīrġanī al-Maḥǧūb al-Makkī.

a-bi-hāmišihi al-Qurʼān al-Maǧīd marsūman bi’r-rasm al-ʿUṯmānī. Except for the sequence IsoHamza+Alif, which was adopted from the Maghreb in 1890 and 1924 (alif+madda didn't work because madda had already been taken for lengthening), everything here is as it was in 1924.

The text of the KFA is not a reconstruction, as al-Ḥusainī al-Ḥaddād al-Mālikī

had told G.Bergsträßer: It does not exactly follow

Abū Dāʾūd Sulaiman Ibn Naǧāḥ al-Andalusī (d. 496/1103)

nor Abu ʿAbdallah Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad al-Ḫarrāz (d. 718/1318),

but (except in about 100 places) the common Warš editions.

The adoption of many Moroccan peculiarities (see above),

some of which were revised in 1952, plus the dropping of Asian characters ‒ plus the fact that the afterword is silent on both ‒ is a clear sign

that al-Ḥusainī al-Ḥaddād al-Mālikī adapted a Warš edition.

All Egyptian readers knew the readings Warš and Qālun.

As a Malikī, al-Ḥusainī al-Ḥaddād probably knew Warš editions

even better than most.

The text, supposedly established in 1924, was not only available in the Maghreb and

in Cairo Warš prints, but also in Būlāq in the century before.

Now to the publication date.

You can find 1919, 1923, 1924 and 1926 in libraries and among scholars.

According to today's library rules, 1924 applies because that is what it says in the first print

But it is not true. It says in the work itself that its printing was on 10.7.1924. But that can only mean that the printing of the Qurʾānic text was completed on that day. The dedication to the king, the message about the completion of printing, could only have been set afterwards; it and the entire epilogue were only printed afterwards, and the work - without a title page, without a prayer at the end - was only bound afterwards - probably again in Būlāq, where it had already been set and assembled - and that was not until 1925, unless ten copies were bound first and then "published", which is not likely.

Because Wikipedia lists Fuʾād's royal monogram as that of his son, here is his (although completely irrelevant): this is a Google translation of one of my German posts

this is a Google translation of one of my German posts

this is a Google translation of one of my German posts

this is a Google translation of one of my German posts

Monday, 3 June 2024

India 1869

In 18609 we have three maṣāḥif, i.e. the British Libray has three maṣāḥif published,

two in Bombay with the same title

إنه القرآن كريم في كتاب مكنون

one with 13 (normal) line

and in the same year

qurʾān maǧīd mutarǧam maḥšī bi-luġāt al-qurʾān

with a translation by Rafīʾud-Dīn Dilavī

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Nairīzī

Mirza Aḥmad an-Nairīzī (ca. 1650–1747) is the last of the classical Iranian calligraher s. Informations are hard to find, because often und...

-

40 years ago Adrian Alan Brockett submitted his Ph.D. to the University of St.Andrews: Studies in Two Transmissions of the Qurʾān . Now...

-

There are several types of madd sign in the Qurʾān, in South Asian masāhif: madd al-muttasil for a longer lengthening of the vowel used...

-

Although it is often written that the King Fuʾād Edition fixed a somehow unclear text, and established the reading of Ḥafṣ according to ʿĀ...