On the basis of some of the oldest manuscripts Marijn van Putten publishes

a muṣḥaf that comes as close as possible to the ʿUṯmānic rasm ‒

not to be confused with the «ʿUṯmānic rasm», that is 300 years younger: deviced by

ad-Dānī.

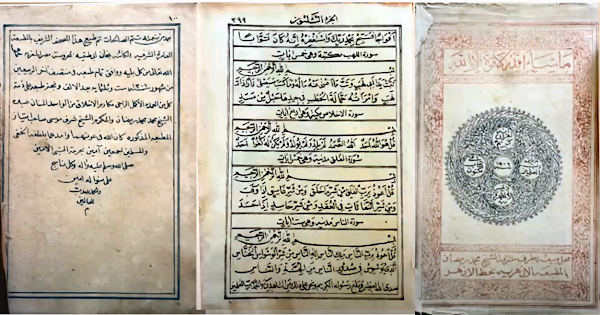

I compare it with the common Maġribian/Andalusian/Egyptian rasm (in an edition from Brunai)

and the Indian one (in edition with 848 pages with 13 lines written by Ḫalīq (al-)Asadī):

Now, that you have seen what "good" editions have made out of the old text, here the same from two "bad" editions: Ottoman from 300 years ago (next to the old text), and Turkish from this century:

I prefer the "Indian" editions, but even Turkish (and Persian) editions are fine.

Wednesday, 22 December 2021

Sunday, 28 November 2021

a map of Zamalek, Gizeh, Bulaq

My first post on the 1924/5 King Fuʾād Edition included a map of Cairo 1920, on which I had marked the Amīriyya Press and the Land Registry (Egyptian Survey Authority) with arrows in the Nile, as well as Midan Tahrir and the place where the government printing press is located since 1972. Also the Ministry of Education and the Nāṣirīya Pedagogical College, where three of the editors worked. The area between Bab al-Luq (in the south-east) and Taufiqia (north of the main railway station) is called Ismailia: the area between the Nile and al-Qāhira (proper) was built up (copying Baron Hausmann's Paris) under Ismail Pascha (1863‒1879 Wali/Governor; in 1867 the Sublime Port recognized the title of "Khedive" for him and his successors); today simply: Downtown.

Everything to the right of the Nile plus the islands is Cairo, everything to the left (Imbaba, Doqqi, Giza) not only does not belong to the city of Cairo, but is in another province.

The two Arabic texts are the 1924 and 1952 printer's notes, both from the copies in the Prussian State Library, which owns copies from five editions.

The two Arabic texts are the 1924 and 1952 printer's notes, both from the copies in the Prussian State Library, which owns copies from five editions.

Important: the typesetting workshop and the offset workshop were well connected by car, tram and boat. The assembled pages did not have a long way to go. Nevertheless: typesetting the text in Būlāq, making a rough proof (Bürstenabzug), making adjustments on the proof (like placing kasra withIN the tails of end-ḥāʾ/ǧīm/ḫāʾ and end-ʿain/ġain, sometimes reducing the space before kāf and after rāʾ/zain and waw); transporting the adjusted proofs to Giza, making plates, printing; transporting the bodies of the book to Būlāq where it was bound and embossed, took more time than planned: Although printed "1342" in the book (see top insert on the map) it was 1343 by the time the books were ready. So the first edition was embossed:

Everything to the right of the Nile plus the islands is Cairo, everything to the left (Imbaba, Doqqi, Giza) not only does not belong to the city of Cairo, but is in another province.

The two Arabic texts are the 1924 and 1952 printer's notes, both from the copies in the Prussian State Library, which owns copies from five editions.

The two Arabic texts are the 1924 and 1952 printer's notes, both from the copies in the Prussian State Library, which owns copies from five editions.Important: the typesetting workshop and the offset workshop were well connected by car, tram and boat. The assembled pages did not have a long way to go. Nevertheless: typesetting the text in Būlāq, making a rough proof (Bürstenabzug), making adjustments on the proof (like placing kasra withIN the tails of end-ḥāʾ/ǧīm/ḫāʾ and end-ʿain/ġain, sometimes reducing the space before kāf and after rāʾ/zain and waw); transporting the adjusted proofs to Giza, making plates, printing; transporting the bodies of the book to Būlāq where it was bound and embossed, took more time than planned: Although printed "1342" in the book (see top insert on the map) it was 1343 by the time the books were ready. So the first edition was embossed:

Wednesday, 24 November 2021

riʾāʾa ‒ sometimes like this; sometimes like that

Already Otto Pretzl had noticed that in Gizeh1924 riʾāʾa was not written the same at the three places it occurs ‒ without the authorities prescribing that.

Iranians and UT2-KFC have the first hamza always after the tooth.

Muṣḥaf al-Azhar aš-Šarīf (Cairo 1978‒1986?) has it always on the tooth:

The others have it sometimes on, sometimes after the tooth.

In 2:264 it is normally on the tooth, except UT2-KFC and Iran.

In 4:38 it is normally after the tooth, except Taj-KFC ‒ probably changed in the next edition (1440h. it is still on the tooth).

In 8:47 all have it after the tooth except Muṣḥaf al-Azhar aš-Šarīf.

Iranians and UT2-KFC have the first hamza always after the tooth.

Muṣḥaf al-Azhar aš-Šarīf (Cairo 1978‒1986?) has it always on the tooth:

The others have it sometimes on, sometimes after the tooth.

In 2:264 it is normally on the tooth, except UT2-KFC and Iran.

In 4:38 it is normally after the tooth, except Taj-KFC ‒ probably changed in the next edition (1440h. it is still on the tooth).

In 8:47 all have it after the tooth except Muṣḥaf al-Azhar aš-Šarīf.

Saturday, 20 November 2021

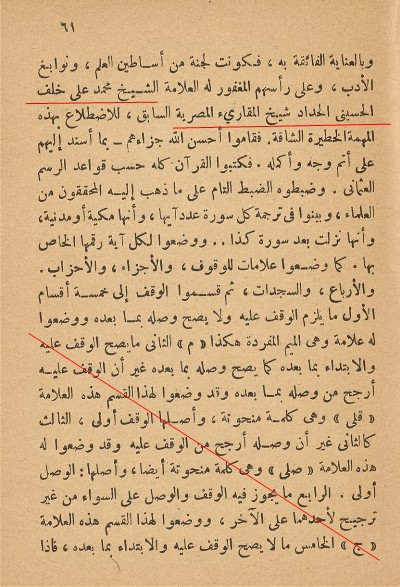

aš-šaiḫ al-maqāriʾ

Just as the KFE of 1924 was prepared by the šaiḫ al-maqāriʾ, the New KFE of 1952 was

prepared by the chief reader of Egypt. But because it was a generation later, it is not

al-Ḥusainī al-Ḥaddād al-Mālikī (d. 22.1. 1939) anymore, but ʿAlī Muḥammad aḍ-Ḍabbāʿ(1304/1886-1380/1960).

Unlike before 1924, when al-Ḥaddād was the only ʿālim who signed the explanations after the qurʾānic text (which means that there wasn't really a committee: the other three stood just for the involvement of the Ministry of Education; they didn't know enough of the Qurʾān to help al-Ḥusainī al-Ḥaddād al-Mālikī), aḍ-Ḍabbāʿ was assisted by ʿulamā'; it was not an Azhār-committee, but one of Azharites, created by the Government Press adviced by the šaiḫ al-Azhar.

They ordered only three changes in the rasm, one graphical nicety,

114 changes in the sura title boxes, forty or so changes at the end of suras with unvoyelled consonants (mostly tanwin) and the beginning of the next (with is now the basmala ‒ unlike 1924 when the first word of the next sura was assumed to follow directly the last one of the preceding sura),

and about 800 changed pauses.

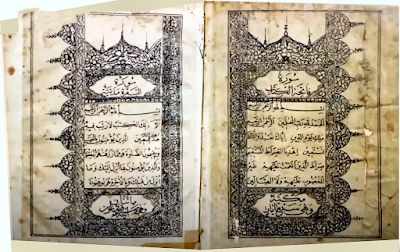

1952 (left) like 1924 (right):

Unlike before 1924, when al-Ḥaddād was the only ʿālim who signed the explanations after the qurʾānic text (which means that there wasn't really a committee: the other three stood just for the involvement of the Ministry of Education; they didn't know enough of the Qurʾān to help al-Ḥusainī al-Ḥaddād al-Mālikī), aḍ-Ḍabbāʿ was assisted by ʿulamā'; it was not an Azhār-committee, but one of Azharites, created by the Government Press adviced by the šaiḫ al-Azhar.

They ordered only three changes in the rasm, one graphical nicety,

114 changes in the sura title boxes, forty or so changes at the end of suras with unvoyelled consonants (mostly tanwin) and the beginning of the next (with is now the basmala ‒ unlike 1924 when the first word of the next sura was assumed to follow directly the last one of the preceding sura),

and about 800 changed pauses.

1952 (left) like 1924 (right):

Friday, 19 November 2021

... and it was never reprinted. And hardly any Egyptian bought it.

It sold so badly that five year later Gotthelf Bergsträßer still could buy copies of the first

print both for himself and for the Bavarian National Library.

Strange that the experts write again and again of THE King Fuʾād Edition,

although there are many, different ones ‒ different not only in size and binding, but in content.

The first one ‒ lets called it KFE I was printed in Giza because only the Egyptian Survey could make offset prints ‒ they had experience in the technique because they produced colour maps.

The second one ‒ KFE Ib ‒ was produced in Būlāq, since the Government Press had aquired

offset presses.

The second one ‒ KFE Ib ‒ was produced in Būlāq, since the Government Press had aquired

offset presses.

Like KFE I ... ... kfe Ib was stamped after binding because the year of publication giving in the book could not be met, so a stamp indicating the next year was put on the bound copy.

There are changes on two pages ‒ both times: right the Giza print, left the first Būlāq print:

At least as important as seals/stamps instead of signatures is an added word. Because there were no gaps between sorts as was typical in Būlāq prints, readers had assumed handwritten pages. The word "model" made clear that al-Ḥusainī al-Ḥaddād al-Mālikī had "only" written a copy for the type setters.

In the third edition ‒ kfe Ic ‒ one more page was changed: the first page afer the qurʾānic text: In the fourth edition ‒ kfe Id ‒ one more page was changed, the only change IN the qurʾānic text before 1952 (in the first line a (silent) nūn was added): Sorry, here the Gizeh print is on the left. Note, that the the second edition, printed in Bulaq is smaller, but largely due to smaller margins. After 1952, for many years there will be two editions: ‒ a bigger one with seven pages on differences between the edition of 1924/5 and the present one (starting 1952) and with all these changes (almost a thousand) being implemented ‒ a smaller one without this information ‒ and with only a small part of the changes made (on the plate of kfe Ib) . Note that the fourth edition is not printed in Gīza (as the fist), not in Būlāq (as the second), but "in Miṣr" ‒ later yet it will be "in al-Qāhira". Let's resume:

all KFEs were Amīriyya editions,

the first one was printed 1924 in Giza

from 1925 to 1972 they were printed in Būlāq but a 1961 print was made in Darb al-Gamāmīz whether by a private printer or a second factory of the press, I do not know, from 1972 to 1975 print was in Imbāba. All KFEs have 827 pages of qurʾānic text with 12 lines

+ 24 (or 22) paginated backmatter pages + four unpaginated pages for the tables of content.

(until 1952: 24 pages, after the revolution: without the leaf mentioning King Fuʾād)

None of the KFEs has a title page;

they are all hardcover and octavo size (20x28 cm the big one, 17x22 cm the small one ‒ the difference is more in the margin than in the text itself)

All KFE-like editions by commercial Egyptian presses and forgein editions (except the Frommann edition) do have title pages, most of them have one continuous pagination.

There was one miniature reprint of KFE I and at least two private editions + the 1955 Peking reprint; of KFE II there were many re-editions, many rearranged with 14 or 15 (often longer) lines ‒ in many sizes, on thinner paper and with different covers ‒ from Bairut to Taschkent.

In Egypt all the time, editions with 522, 525 (later 604) pages of qurʾānic text were more popular.

For the 15 lines, 525 page, type set Amīriyya print (Muṣḥaf al-Azhar aš-Šarīf) follow the link.

The changes of the second, third and fourth edition did not survive the big change of 1952, which had about 900 changes, but reverted in things just mentioned ("dedication", aṣl, extra nūn in allan) to the first print.

Many private and foreign reprints (and later ʿUṯmān Ṭaha) keep the silent nūn.

Strange that the experts write again and again of THE King Fuʾād Edition,

although there are many, different ones ‒ different not only in size and binding, but in content.

The first one ‒ lets called it KFE I was printed in Giza because only the Egyptian Survey could make offset prints ‒ they had experience in the technique because they produced colour maps.

The second one ‒ KFE Ib ‒ was produced in Būlāq, since the Government Press had aquired

offset presses.

The second one ‒ KFE Ib ‒ was produced in Būlāq, since the Government Press had aquired

offset presses.Like KFE I ... ... kfe Ib was stamped after binding because the year of publication giving in the book could not be met, so a stamp indicating the next year was put on the bound copy.

There are changes on two pages ‒ both times: right the Giza print, left the first Būlāq print:

At least as important as seals/stamps instead of signatures is an added word. Because there were no gaps between sorts as was typical in Būlāq prints, readers had assumed handwritten pages. The word "model" made clear that al-Ḥusainī al-Ḥaddād al-Mālikī had "only" written a copy for the type setters.

In the third edition ‒ kfe Ic ‒ one more page was changed: the first page afer the qurʾānic text: In the fourth edition ‒ kfe Id ‒ one more page was changed, the only change IN the qurʾānic text before 1952 (in the first line a (silent) nūn was added): Sorry, here the Gizeh print is on the left. Note, that the the second edition, printed in Bulaq is smaller, but largely due to smaller margins. After 1952, for many years there will be two editions: ‒ a bigger one with seven pages on differences between the edition of 1924/5 and the present one (starting 1952) and with all these changes (almost a thousand) being implemented ‒ a smaller one without this information ‒ and with only a small part of the changes made (on the plate of kfe Ib) . Note that the fourth edition is not printed in Gīza (as the fist), not in Būlāq (as the second), but "in Miṣr" ‒ later yet it will be "in al-Qāhira". Let's resume:

all KFEs were Amīriyya editions,

the first one was printed 1924 in Giza

from 1925 to 1972 they were printed in Būlāq but a 1961 print was made in Darb al-Gamāmīz whether by a private printer or a second factory of the press, I do not know, from 1972 to 1975 print was in Imbāba. All KFEs have 827 pages of qurʾānic text with 12 lines

+ 24 (or 22) paginated backmatter pages + four unpaginated pages for the tables of content.

(until 1952: 24 pages, after the revolution: without the leaf mentioning King Fuʾād)

None of the KFEs has a title page;

they are all hardcover and octavo size (20x28 cm the big one, 17x22 cm the small one ‒ the difference is more in the margin than in the text itself)

All KFE-like editions by commercial Egyptian presses and forgein editions (except the Frommann edition) do have title pages, most of them have one continuous pagination.

There was one miniature reprint of KFE I and at least two private editions + the 1955 Peking reprint; of KFE II there were many re-editions, many rearranged with 14 or 15 (often longer) lines ‒ in many sizes, on thinner paper and with different covers ‒ from Bairut to Taschkent.

In Egypt all the time, editions with 522, 525 (later 604) pages of qurʾānic text were more popular.

For the 15 lines, 525 page, type set Amīriyya print (Muṣḥaf al-Azhar aš-Šarīf) follow the link.

The changes of the second, third and fourth edition did not survive the big change of 1952, which had about 900 changes, but reverted in things just mentioned ("dedication", aṣl, extra nūn in allan) to the first print.

Many private and foreign reprints (and later ʿUṯmān Ṭaha) keep the silent nūn.

Thursday, 18 November 2021

The Sanaʿāʾ Palimpsest

When I started to blog,

I said that the times are exciting because of

old Arabic inscriptions being deciphered,

the Sanaʿāʾ fragments, esp. the S.P.,

and because we understand that manuscripts belonging to different collections

once were one muṣḥaf.

One of the first who had access to the high-resolution and to the ultra-violett images of the S.P. made by Sergio Noja Noseda and Christian Robin was Asma Hilali. She was (one of) the first who published about them not on the basis of the UNESCO CD and the Bothmer/Puin black and white images.

She made two mistakes:

She only looked with her eyes, not with her brain.

But where the scriptio superior covers the scriptio inferior

one has to connected the visible parts assuming possible letterforms,

one has to speculate in order to fill gaps ‒ knowing the quranic vocabulary one has to try to put in as many letters as are fitting.

Because Asma Hilali lacks phantasy or abhors speculation she reads less than a third of what has been written.

And she mistakes a library signature, a collection convolute for a meaningful document.

As an introduction into the study of Islamic manuscripts one should read Islamic-Awarness.org.

Please read 3. Ḥijāzī & Kufic Manuscripts Of The Qur'ān From 1st Century Of Hijra Present In Various Collections; in the first column you see up to seven "Designations" for parts of the same document.

for the Codex Ṣanʿāʾ I

Only if you look at the document as as a whole, you have a chance to make sense of the parts.

Not only did Asma Hilali only study 36 folios of the 81 folios of the surving fragments of the document, she did not sort out the four fragments that do not belong to it that are classified as parts of DAM 01-27.1

That Asma Hilali made these two essential mistakes, is not that bad.

At least she was quick.

But that she refused to learn, declined to revise her findings in light of what others had found out, is a sign of stupidity.

I know: Everybody is polite, just says that she is (overtly) cautious.

I say: She is blind, cowish, mad.

Everybody (Elisabeth, Mohsen, Behnam, Alba, Eléonore, and in the second row Marijn, Nicolai, Franҫois) agree that both levels are part of a muṣḥaf. The quire structure is proof enough, the pages continue where the page before had ended. Asma Ḥilali is alone in postulating "scribal exercises".

That different scribes wrote different pages, is no a valid argument against all being part of one muṣḥaf, because Fr. Deroche had found out, that that was common in the frist two centuries.

A positive reviewer, J.A. Gilcher, wrote about The Sanaa Palimpsest The Transmission of the Qur'an in the First Centuries AH Oxford University Press 2017:

It would be nice to see the Documenta Coranica tome by Hadiya Gurtmann once annouced by Corpus Coranicum, to see how wrong she is. I can only speculate why Michael Marx waits with the publication.

Here is an image of the backside of the second folio of DAM 1.27.1 And here Hadiya Gurtmann's reconstruction of the lower text (image taken from Fr. Deroche's Le Coran, une histoire plurielle : essai sur la formation du texte coranique, Paris, 2019 ‒ he got it from Michael Marx; Hadiya Gurtmann had worked at Corpus Coranicum)

I say that A.H. is mad too, because she refuses to learn in the field of Koran prints, too.

In "her" conference the Egyptian librarians all the time spoke of "muṣḥaf al-malik Fuʾād", "muṣḥaf al-Amīriyya", "muṣḥaf al-ḥukūma", she alone refered to "muṣḥaf al-Qāhira" and "ṭabʿa al-Qāhira", although the first term is used for manuscripts and the 1924 copy was printed in Giza, which belongs not even to the governorate of Cairo, not printed in al-Qāhira, not even in Cairo.

Above are Cairo editions shown during the conference.

In this blog I have shown many more ‒ especially Cairo editions of riwāya Warš because I find it remarkable that most experts take it for granted that a muṣḥaf contains Ḥafṣ, basta!

And this is the page at the end of the object of the conference

informing everybody willing to take note

that it was printed in Giza. And that's not all.

And that's not all.

Not only that it is NOT a Cairo print,

it is not even a 1924 edition.

In 1924 the quranic text was printed,

but after that the backmatter had to be set, made into plates, and printed.

Then the book had to be bound.

By the time it was published, the year was 1925.

Therefore the first edition was embossed:

طبعة الحكومية المصرّية

-- . --

١٣٤٣ هجرّية

سـنة

old Arabic inscriptions being deciphered,

the Sanaʿāʾ fragments, esp. the S.P.,

and because we understand that manuscripts belonging to different collections

once were one muṣḥaf.

One of the first who had access to the high-resolution and to the ultra-violett images of the S.P. made by Sergio Noja Noseda and Christian Robin was Asma Hilali. She was (one of) the first who published about them not on the basis of the UNESCO CD and the Bothmer/Puin black and white images.

She made two mistakes:

She only looked with her eyes, not with her brain.

But where the scriptio superior covers the scriptio inferior

one has to connected the visible parts assuming possible letterforms,

one has to speculate in order to fill gaps ‒ knowing the quranic vocabulary one has to try to put in as many letters as are fitting.

Because Asma Hilali lacks phantasy or abhors speculation she reads less than a third of what has been written.

And she mistakes a library signature, a collection convolute for a meaningful document.

As an introduction into the study of Islamic manuscripts one should read Islamic-Awarness.org.

Please read 3. Ḥijāzī & Kufic Manuscripts Of The Qur'ān From 1st Century Of Hijra Present In Various Collections; in the first column you see up to seven "Designations" for parts of the same document.

for the Codex Ṣanʿāʾ I

Only if you look at the document as as a whole, you have a chance to make sense of the parts.

Not only did Asma Hilali only study 36 folios of the 81 folios of the surving fragments of the document, she did not sort out the four fragments that do not belong to it that are classified as parts of DAM 01-27.1

That Asma Hilali made these two essential mistakes, is not that bad.

At least she was quick.

But that she refused to learn, declined to revise her findings in light of what others had found out, is a sign of stupidity.

I know: Everybody is polite, just says that she is (overtly) cautious.

I say: She is blind, cowish, mad.

Everybody (Elisabeth, Mohsen, Behnam, Alba, Eléonore, and in the second row Marijn, Nicolai, Franҫois) agree that both levels are part of a muṣḥaf. The quire structure is proof enough, the pages continue where the page before had ended. Asma Ḥilali is alone in postulating "scribal exercises".

That different scribes wrote different pages, is no a valid argument against all being part of one muṣḥaf, because Fr. Deroche had found out, that that was common in the frist two centuries.

A positive reviewer, J.A. Gilcher, wrote about The Sanaa Palimpsest The Transmission of the Qur'an in the First Centuries AH Oxford University Press 2017:

As Work in Progress, mistakes, corrections, fragmented readings, its intended use written in a fragmentary fashion consisting of multiple sessions of teaching or dictation circle intended for experimental use in workshop-like circles, always destined to be destroyed, didactic techniques of a circle of teaching sessions, for Hilali, the fact that the parchment was eventually used as a palimpsest for later text is proof of its purpose from the beginning to be recycled in the futureGiven the fact, that her base asumption is wrong, I see no point in going through the 4000 letters were her reading (or absence of reading) differs from that of others. I am sure that in over 98% she is wrong.

It would be nice to see the Documenta Coranica tome by Hadiya Gurtmann once annouced by Corpus Coranicum, to see how wrong she is. I can only speculate why Michael Marx waits with the publication.

Here is an image of the backside of the second folio of DAM 1.27.1 And here Hadiya Gurtmann's reconstruction of the lower text (image taken from Fr. Deroche's Le Coran, une histoire plurielle : essai sur la formation du texte coranique, Paris, 2019 ‒ he got it from Michael Marx; Hadiya Gurtmann had worked at Corpus Coranicum)

I say that A.H. is mad too, because she refuses to learn in the field of Koran prints, too.

In "her" conference the Egyptian librarians all the time spoke of "muṣḥaf al-malik Fuʾād", "muṣḥaf al-Amīriyya", "muṣḥaf al-ḥukūma", she alone refered to "muṣḥaf al-Qāhira" and "ṭabʿa al-Qāhira", although the first term is used for manuscripts and the 1924 copy was printed in Giza, which belongs not even to the governorate of Cairo, not printed in al-Qāhira, not even in Cairo.

Above are Cairo editions shown during the conference.

In this blog I have shown many more ‒ especially Cairo editions of riwāya Warš because I find it remarkable that most experts take it for granted that a muṣḥaf contains Ḥafṣ, basta!

And this is the page at the end of the object of the conference

informing everybody willing to take note

that it was printed in Giza.

And that's not all.

And that's not all.Not only that it is NOT a Cairo print,

it is not even a 1924 edition.

In 1924 the quranic text was printed,

but after that the backmatter had to be set, made into plates, and printed.

Then the book had to be bound.

By the time it was published, the year was 1925.

Therefore the first edition was embossed:

طبعة الحكومية المصرّية

-- . --

١٣٤٣ هجرّية

سـنة

Saturday, 13 November 2021

Muṣṭafā / ʿĪsā al-Bābī al-Ḥalabī

1858 Aḥmad from al-Bāb, north-east of Aleppo, came to Cairo and together with others

opened a publishing house. Having no children he invited his cousins to join him and

they took over the enterprise becoming Muṣṭafā al-Bābī al-Ḥalabī

I have been in two offices,

one behind the Azhar

und eines am -- nach dem Verlag benannten -- Midan al-Halabi

al-Muḫallalātī

Many think that the 1924 print was the first with the ʿUṯmānic rasm.

That's not correct.

Already for a long time India had producecd maṣāḥif with the defective rasm.

So had Morocco.

And in 1308/1890 in Egypt a muṣḥaf with the ʿUṯmānic rasm according to ad-Dānī was printed.

That's not correct.

Already for a long time India had producecd maṣāḥif with the defective rasm.

So had Morocco.

And in 1308/1890 in Egypt a muṣḥaf with the ʿUṯmānic rasm according to ad-Dānī was printed.

Monday, 8 November 2021

Tom Milo ‒ mushafmuscat.om ‒ mushaf oman

God news about Tom Milos mushafmuscat.om

Thomas Milo analysed the best examples of high Ottoman calligraphy = court calligraphy, synthesized its Grammar (term coined by him) ‒ ignoring all other (lesser) Ottoman calligraphers.

He and his team succeded in aping human writing: first the stroke, then the dots, at last the additional signs. Like the writers of old, the signs of each category have to be in the right order, but they don't have to be exactely above resp. below the character that they modify.

In Kein Standard I critisized a word in 4:4, where Milo placed a madda above a consonant, although according to G24 (followed strictly by ʿUṯmān Ṭaha) madda can only sit above a vowel ‒ šadda "lengthening" consonants.

Today I looked at 4:4 again and low and behold, the wrongly placed (blue) madda was moved to its proper place: Thomas Milo had to be flexible all the time. In his view dots belong to letters including its connection to the next resp. its tail signaling: End Letter. But the Omanis thought that the dots belong to the "heart" of the letter, the tooth resp. the defining part.

Milo wanted staked lettergroups, Omanis prefered baseline letters with a clear right-to-left order. Milo agreed to half way solutions.

His elektronic Muṣḥaf is marvellous!

But Oman never had it printed. A printed, a bound codex does not exist.

Instead a Muṣḥaf ʿOmān was calligraphed by Qadusi and printed ‒ by the way not as strictly simplified as ʿUṯmān Ṭaha, hardly less Ottoman than Milo's electronic muṣḥaf.

Thomas Milo analysed the best examples of high Ottoman calligraphy = court calligraphy, synthesized its Grammar (term coined by him) ‒ ignoring all other (lesser) Ottoman calligraphers.

He and his team succeded in aping human writing: first the stroke, then the dots, at last the additional signs. Like the writers of old, the signs of each category have to be in the right order, but they don't have to be exactely above resp. below the character that they modify.

In Kein Standard I critisized a word in 4:4, where Milo placed a madda above a consonant, although according to G24 (followed strictly by ʿUṯmān Ṭaha) madda can only sit above a vowel ‒ šadda "lengthening" consonants.

Today I looked at 4:4 again and low and behold, the wrongly placed (blue) madda was moved to its proper place: Thomas Milo had to be flexible all the time. In his view dots belong to letters including its connection to the next resp. its tail signaling: End Letter. But the Omanis thought that the dots belong to the "heart" of the letter, the tooth resp. the defining part.

Milo wanted staked lettergroups, Omanis prefered baseline letters with a clear right-to-left order. Milo agreed to half way solutions.

His elektronic Muṣḥaf is marvellous!

But Oman never had it printed. A printed, a bound codex does not exist.

Instead a Muṣḥaf ʿOmān was calligraphed by Qadusi and printed ‒ by the way not as strictly simplified as ʿUṯmān Ṭaha, hardly less Ottoman than Milo's electronic muṣḥaf.

Saturday, 6 November 2021

"the Cairo Edition"

Ik bedoel jou, de beste Curanoloog, als wat er met Gotthelf, Otto, Theo en Pim is gebeurd, niet met jou gebeurt.

Als het op transcriberen aankomt, ben je erg precies. Als het gaat om edities, drukken, versies, recensies, ben je slordig.

editie betekent = "bepaalde druk van een ... boek"

uitgave, exemplaren die in één keer gedrukt worden, druk van een boek

1) Aantal gedrukte exemplaren 2) Aantal te drukken exemplaren 3) Aflevering 4) Boekuitgave 5) Deel van een krantenoplage 6) Druk 7) Druk van een boek 8) Oplaag 9) Oplaag van een boek 10) Oplage 11) Oplage van boeken

Is verschillend van "teksteditie/ tekstuitgave".

edition = The entire number of copies of a publication issued at one time or from a single set of type. / The entire number of like or identical items issued or produced as a set

Édition (Nom commun)

[e.di.sjɔ̃] / Féminin

Impression, publication et diffusion d’une œuvre artistique (livre, musique, objet d’art, etc). soit qu’elle paraisse pour la première fois, soit qu’elle ait déjà été imprimé ; ou les séries successives des exemplaires qu’on imprime pour cette publication.

Totalité des exemplaires de tel ou tel ouvrage publié et mis en vente.

Par extension, l’industrie qui a pour objet la publication d’ouvrage.

Tirage spécifique de la même édition d’un ouvrage.

Exemplaire faisant partie d’un tirage dans une édition.

(Journalisme) Tirage strictement identique de l’édition du jour d’un quotidien.

In het Frans is het bijzonder duidelijk: « maison d'édition » betekent een uitgeverij.

"editie" is niet wat an editor/een redacteur doet, maar wat an publisher/een uitgever doet.

Als je naar klassieke Arabische werken kijkt, waren er tot voor kort meestal twee of drie edities: één uit Leiden en één uit Cairo, één uit Göttingen en één uit Oxford. Hier, "the Cairo edition" maakt geen probleem.

Maar met de Koran is het anders: er zijn tegenwoordig duizenden edities. Alleen al uit Cairo zijn er tien belangrijke uitgaven van de Warš lezing.

Here two images from a 1929 Cairo Warš Edition ‒ without a title page, as was common at the time:

And here from two of the oldest al-Qahira publishers, i.e. not from Bab al-Khalq, al-Faggala, from Bulaq or even Giza but from "behind" al-Azhar:

Apart from these 100% Cairo Editions, there are editions conceaved in Morocco resp. Algeria, but produced in Cairo ‒ the Moroccan ones without production place, the Algerian ones with an Algerian publisher's name. (Only the third edition of the third sherifian muṣḥaf was produced in Morocco.)

Er is niet meer "de editie van Caïro" dan er "de Ayatollah" of "de roman van Parijs" is.

Alleen drukwerkspecialisten zijn geïnteresseerd in drukwerk (hoeveel regels per pagina, hoeveel pagina's per ǧuz, aanduiding van chronologie, saǧadat, sakatāt, typografie, kalligrafie...). Curanaloogen zijn geïnteresseerd in de rasmen, de verzendingen, de orthografie.

Zelfs als we alleen kijken naar de belangrijkste Ḥafṣ uitgaven, zijn er enkele uit 1881, 1890, 1924, 1952, 1975, 1976. Zelfs de uitgaven van de Amīriyya uit 1926 en 1929 verschillen van de Gizeh-prent uit 1924.

Ik weet niet welke editie bedoeld wordt ‒ zou kunnen bedoeld worden ‒ met "cairo edition".

Ik heb de indruk dat u de Uthman rasm bedoelt, het gebruikelijke schrift zonder extra alifen, dat gebruikelijk werd in het Ottomaanse Rijk en Iran.

De prent van Gizeh uit 1924 is bijna nergens in de islamitische wereld te vinden, maar vaak wel in Duitse, Nederlandse en Zwitserse bibliotheken.

80% van de Moslims gebruiken totaal verschillende uitgaven, zij het verschillende lezingen, zij het verschillende spellingen. Tot in de jaren tachtig gebruikten de Arabers van Mašriq ook overwegend Ottoaanse edities.

Tegenwoordig gebruiken veel Arabieren, Maleisiërs en Salafisten edities in de spelling van de 1952 editie van de Koran, maar alleen Oriëntalisten hebben ooit de Amīriyya editie gebruikt.

Een derde van de moslims is afkomstig van het Indiase subcontinent, zodat Indiase kwesties wereldwijd het meest voorkomen.

Bijna een zesde van de moslims gebruikt Indonesische edities.

Turkije heeft zijn eigen standaard, Iran heeft er meerdere.

Als het op transcriberen aankomt, ben je erg precies. Als het gaat om edities, drukken, versies, recensies, ben je slordig.

editie betekent = "bepaalde druk van een ... boek"

uitgave, exemplaren die in één keer gedrukt worden, druk van een boek

1) Aantal gedrukte exemplaren 2) Aantal te drukken exemplaren 3) Aflevering 4) Boekuitgave 5) Deel van een krantenoplage 6) Druk 7) Druk van een boek 8) Oplaag 9) Oplaag van een boek 10) Oplage 11) Oplage van boeken

Is verschillend van "teksteditie/ tekstuitgave".

edition = The entire number of copies of a publication issued at one time or from a single set of type. / The entire number of like or identical items issued or produced as a set

Édition (Nom commun)

[e.di.sjɔ̃] / Féminin

Impression, publication et diffusion d’une œuvre artistique (livre, musique, objet d’art, etc). soit qu’elle paraisse pour la première fois, soit qu’elle ait déjà été imprimé ; ou les séries successives des exemplaires qu’on imprime pour cette publication.

Totalité des exemplaires de tel ou tel ouvrage publié et mis en vente.

Par extension, l’industrie qui a pour objet la publication d’ouvrage.

Tirage spécifique de la même édition d’un ouvrage.

Exemplaire faisant partie d’un tirage dans une édition.

(Journalisme) Tirage strictement identique de l’édition du jour d’un quotidien.

In het Frans is het bijzonder duidelijk: « maison d'édition » betekent een uitgeverij.

"editie" is niet wat an editor/een redacteur doet, maar wat an publisher/een uitgever doet.

Als je naar klassieke Arabische werken kijkt, waren er tot voor kort meestal twee of drie edities: één uit Leiden en één uit Cairo, één uit Göttingen en één uit Oxford. Hier, "the Cairo edition" maakt geen probleem.

Maar met de Koran is het anders: er zijn tegenwoordig duizenden edities. Alleen al uit Cairo zijn er tien belangrijke uitgaven van de Warš lezing.

Here two images from a 1929 Cairo Warš Edition ‒ without a title page, as was common at the time:

And here from two of the oldest al-Qahira publishers, i.e. not from Bab al-Khalq, al-Faggala, from Bulaq or even Giza but from "behind" al-Azhar:

Apart from these 100% Cairo Editions, there are editions conceaved in Morocco resp. Algeria, but produced in Cairo ‒ the Moroccan ones without production place, the Algerian ones with an Algerian publisher's name. (Only the third edition of the third sherifian muṣḥaf was produced in Morocco.)

Er is niet meer "de editie van Caïro" dan er "de Ayatollah" of "de roman van Parijs" is.

Alleen drukwerkspecialisten zijn geïnteresseerd in drukwerk (hoeveel regels per pagina, hoeveel pagina's per ǧuz, aanduiding van chronologie, saǧadat, sakatāt, typografie, kalligrafie...). Curanaloogen zijn geïnteresseerd in de rasmen, de verzendingen, de orthografie.

Zelfs als we alleen kijken naar de belangrijkste Ḥafṣ uitgaven, zijn er enkele uit 1881, 1890, 1924, 1952, 1975, 1976. Zelfs de uitgaven van de Amīriyya uit 1926 en 1929 verschillen van de Gizeh-prent uit 1924.

Ik weet niet welke editie bedoeld wordt ‒ zou kunnen bedoeld worden ‒ met "cairo edition".

Ik heb de indruk dat u de Uthman rasm bedoelt, het gebruikelijke schrift zonder extra alifen, dat gebruikelijk werd in het Ottomaanse Rijk en Iran.

De prent van Gizeh uit 1924 is bijna nergens in de islamitische wereld te vinden, maar vaak wel in Duitse, Nederlandse en Zwitserse bibliotheken.

80% van de Moslims gebruiken totaal verschillende uitgaven, zij het verschillende lezingen, zij het verschillende spellingen. Tot in de jaren tachtig gebruikten de Arabers van Mašriq ook overwegend Ottoaanse edities.

Tegenwoordig gebruiken veel Arabieren, Maleisiërs en Salafisten edities in de spelling van de 1952 editie van de Koran, maar alleen Oriëntalisten hebben ooit de Amīriyya editie gebruikt.

Een derde van de moslims is afkomstig van het Indiase subcontinent, zodat Indiase kwesties wereldwijd het meest voorkomen.

Bijna een zesde van de moslims gebruikt Indonesische edities.

Turkije heeft zijn eigen standaard, Iran heeft er meerdere.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Nairīzī

Mirza Aḥmad an-Nairīzī (ca. 1650–1747) is the last of the classical Iranian calligraher s. Informations are hard to find, because often und...

-

There are several types of madd sign in the Qurʾān, in South Asian masāhif: madd al-muttasil for a longer lengthening of the vowel used...

-

40 years ago Adrian Alan Brockett submitted his Ph.D. to the University of St.Andrews: Studies in Two Transmissions of the Qurʾān . Now...

-

Although it is often written that the King Fuʾād Edition fixed a somehow unclear text, and established the reading of Ḥafṣ according to ʿĀ...